(Part 1 of 3)

On the night before we leave for Agra, I mention to our driver that we’d like to stop at the town prominent in the Mughal Empire, Sikandra.

Deepak gazes at me long and in silence.

I explain. You know, it’s on the road into Agra. Akbar ka rauza aur Maryam ka rauza. Gesticulating. Lamba chauda. Road se dikhega. Vo thai Padshah, aur Maryam unki bibi. (For those of you who don’t understand my, er, abbreviated Hindi: Akbar’s and Maryam’s tombs, imposing monument, can be seen from the road. He was emperor, and Maryam was his wife).

His expression does not change. But, I’m not disheartened. Deepak’s a man of few words.

Who’s Maryam, and who’s Jodha? Are they one and the same?

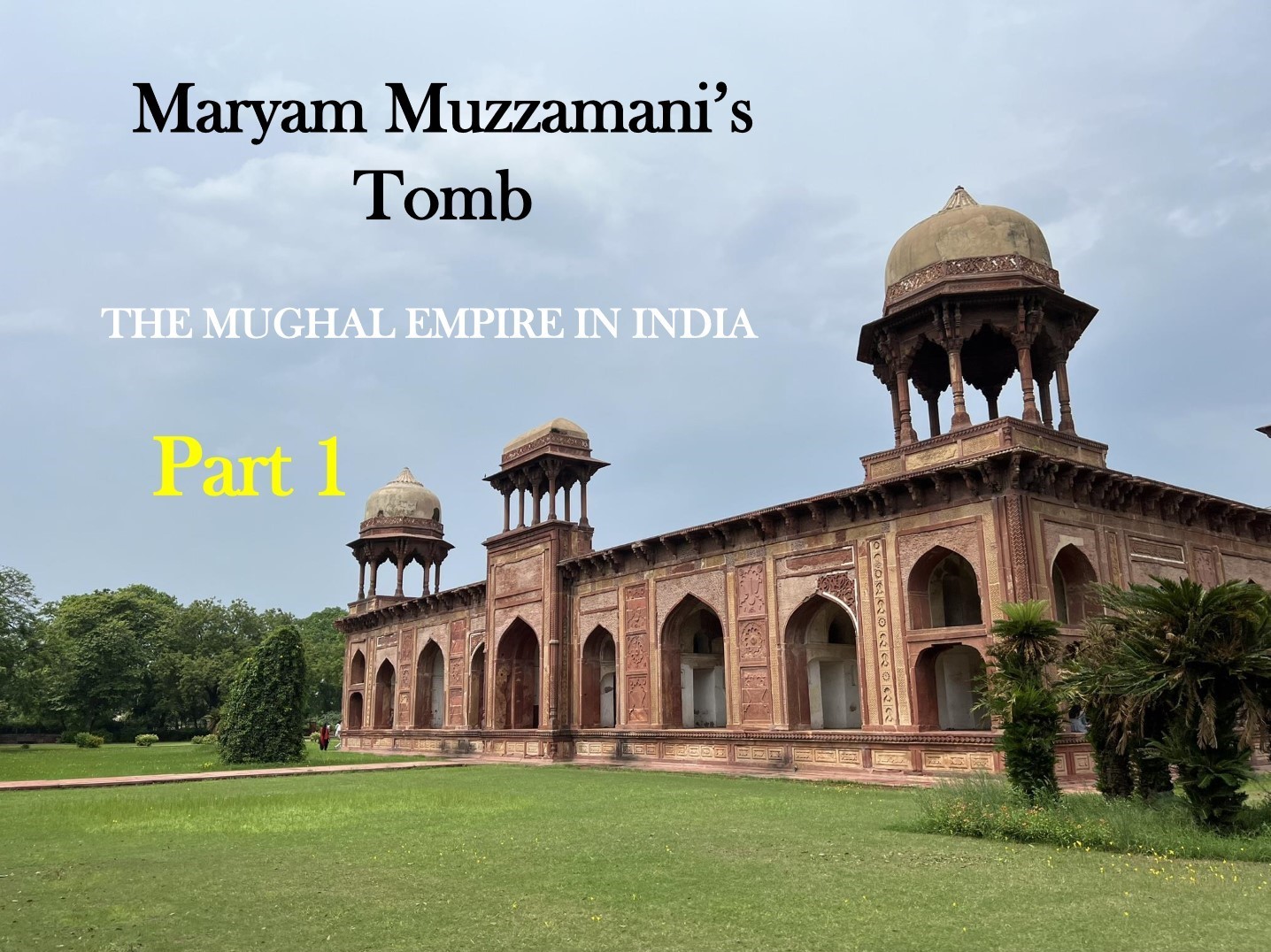

Akbar’s Hindu wife (unnamed), who was bestowed with the title of Maryam Muzzamani when she gave birth to his heir, Prince Salim/Emperor Jahangir, is buried in a tomb at Sikandra, across the contemporary highway from his tomb.

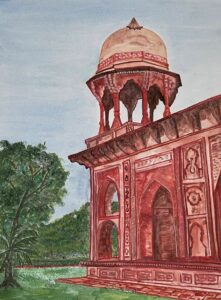

Maryam Muzzamani’s tomb at Sikandara, near Agra.

But, in current popular imagination, there’s another Hindu wife, Jodha Bai. Movies have been made about their love story; she’s a principal character in the Mughal harem in television series. And, at every one of my talks and lectures on the Mughal Empire, someone invariably asks about her.

‘Jodha Bai,’ only known as such because she was a princess of the kingdom of Jodhpur. But, her real name was Jagat Gosini, and this particular ‘Jodha’ was married to Akbar’s son, Emperor Jahangir. As for Akbar’s Jodha? Read on. . .

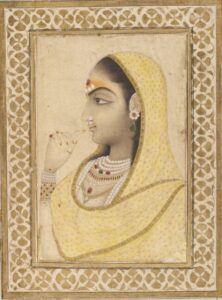

Fun fact: The Mughals were enormously, beyond-belief wealthy—those are real pearls, emeralds and rubies on the empress. Image Source.

But, did Jodha actually exist? I will delve into her story in this blog post, even as we visit the tomb of the other wife, Maryam.

But first, back to our driver. . .

The next day as we greet each other, Deepak’s all smiles, having studied the map on his phone, I guess. I don’t realize until our return trip—when we take the Yamuna Expressway—that this is now the more frequented route into Agra from Delhi. It cuts some two hours of travel time, and bypasses Sikandra.

Which means that anyone wishing to visit Akbar’s tomb, will have to retrace their way toward Delhi on the old Delhi-Agra National Highway. And so, I suspect, fewer tourists come here now.

This National Highway is a comparatively leisurely route, clustered with tiny towns and villages of ancient lineage that hamper your speed. Ancient, because it follows, more or less, a 16th Century road.

And, in evidence of its antiquity, there is litter of kos minars, mile markers of sorts that date to the Mughal Empire in India.

How the Mughal Empire measured distance:

As part of their administrative duties, the Mughal kings in India (1526-1858) built and maintained roads for ease of travel within the Mughal Empire. They weren’t the first to employ the use of these milestones; there are mentions of similar pillars in Emperor Asoka’s time (c. 300 BCE).

The Delhi to Agra route was possibly the first that the Mughal kings invested in. The first Mughal emperor established his base at Agra after conquering Delhi, and so, a large part of northern India. Both cities lie along the Yamuna River, and Agra was more easily protected and fortified than Delhi.

Kos minars on the way to Agra from Delhi, along the old highway of the Mughal Empire.

So on this road, as in others (Delhi to Lahore, Delhi to Peshawar etc.), the Mughals beat back the jungle, cleared a pathway, erected sarais or rest houses for weary travelers, dug wells at intervals for water, and planted giant trees for fruit and shade—the mango, the jamun, the tamarind, and the Indian rosewood.

And then, they raised the chess pawn-like structures built of brick and red sandstone at intervals of a little more than two miles—a kos measure—to mark the journey for the traveler.

There aren’t, however, too many of the kos minars remaining today on the way to Agra.

Some abut the highway as you clip past them, head whipping around to catch a glimpse. Some obligingly sit a little distance from the road, rising amidst the yellow flowers of winter mustard fields, etched against a limpid blue sky, or shrouded in fog.

The Mughals and the British in India:

Officially, the rule of the Mughal Empire lasted from 1526 (The First Battle of Panipat) to 1858, when the British colonized India and brought the country under the dominion of Queen Victoria.

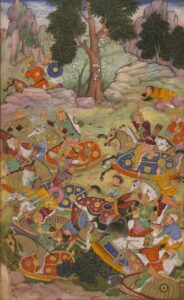

The First Battle of Panipat, illustrated in the Baburnama. Babur, with his 25,000 strong army, confronted the Delhi Sultan Ibrahim Khan Lodi with his 100,000 troops and a thousand elephants. Babur had a surreptitious weapon though, firepower, used for the first time in an Indian battlefield (although guns did exist in India before). Image Source.

In actuality, it’s only the first six Mughal emperors who held a firm sway over the subcontinent, ending with Emperor Aurangzeb’s rule in 1707.

The British first came to India in the guise of the English East India Company early in the 17th Century, and had been making inroads into both trade and military campaigns when Aurangzeb died.

Over the next century and a half, the Mughal Empire disintegrated in royal family squabbles, disenchanted vassals shedding away at the fringes–usually with the aid of British armies–until the Company held more authority than the figurehead Mughal emperor in Delhi.

Emperor Babur, well before that:

The first Mughal emperor, Babur, a princeling of the province of Fergana (current-day Uzbekistan), had been kicked out of his inheritance. Babur was soon lord over Kabul and Samarkand, when he was invited to battle the ruler of Delhi, Ibrahim Khan Lodi.

He’d made rampaging forays into northwestern India before, and it’s possible that the disgruntled nobles in Lodi’s court imagined that he would defeat Lodi and go back. He didn’t; he conquered Delhi and stayed on, knowing that if he left, all his annexations would barely survive his trip back to Kabul.

Emperor Babur did not last very long either; he died in 1530, four years after his conquest of India.

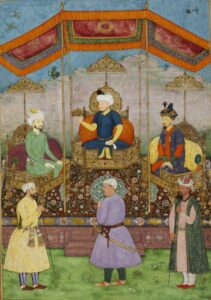

An idealized portrait of Babur (left) and his son, Humayun (right). Seated between them is their most-famous progenitor, Timur the Lame, who is in the process of handing the crown of the Mughal Empire to Babur. In front of the three kings are their prime ministers. The man in front of Emperor Humayun is Bairam Khan. Bairam eventually became regent when Humayun’s son, Akbar, came to the throne as a minor. Image Source.

Emperor Humayun, the trustful, the ingenuous, the stupid?

Babur’s son, Emperor Humayun, was an indulgent man toward his half-brothers who held the governorships of Lahore and Kabul within his Mughal Empire. Now, this is a weakness in any sovereign, who ought to know no affections, acknowledge no kin. Humayun ruled for ten years, and with scant help from his brothers, was driven out of India, eventually seeking refuge at the court of the Shah of Iran.

The Shah offered him help with an army, with the caveat that on his way back into India, Humayun would conquer Kabul and Lahore and render them to the Shah as payment.

Humayun came back in 1555, defeated the ruling Delhi king, and. . .did not transfer the two kingdoms to the Shah of Iran because they were important gateways—and so defenses—to his rekindled Mughal Empire.

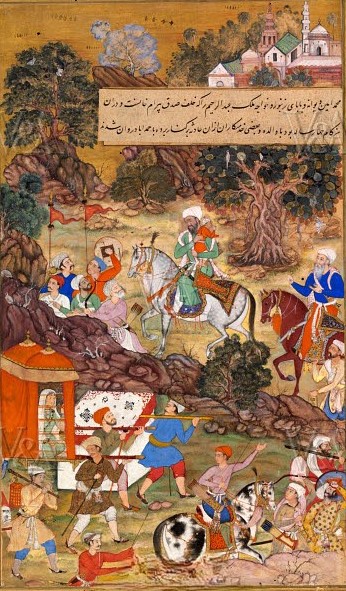

Emperor Humayun, on his way back into India after his long exile, stops to conquer Kabul and defeat his brother, Kamran. Again, exquisite detail, in the armor of the war horses, and on the left, the falling of Kamran’s standard. On the battlefield, this was a signal to his army that he’s been slain. Image Source.

Six months after this hard-fought homecoming, Emperor Humayun slipped and fell down a steep flight of stairs at the Purana Qila (the Old Fort) in Delhi in his haste to answer the adhan, the call to prayer from the mosque.

This was on the 24th of January, 1556.

Three days later, on the 27th, he was dead.

And so, we come to Akbar, Maryam’s and Jodha’s husband:

Humayun’s son, Akbar, was in northwest Punjab, some three hundred miles away, performing his duties as governor of the province under the guardianship of Bairam Khan, the Khan-i-khanan, the Commander-in-chief of the Mughal armies.

In Delhi, courtiers had already kept the gravity of Emperor Humayun’s fall secret, deflecting questions as to why he hadn’t shown himself (often/frequent, perhaps even daily) to the public at an upper balcony.

One of the upper balconies of the Sher Mandal in Delhi. Emperor Humayun was on the terrace above, when he slipped on the stairs leading down.

(This practice, a jharoka, was continued by subsequent Mughal emperors—I’m not quite sure if the Mughals appropriated the daily jharoka from their own Chagatai Turki ancestry, or borrowed it from early Indian history–see my post on the Airavateshwar Temple in southern India, where a South Indian Chola king from the 3rd Century also gives daily audiences).

Now, runners sped over indifferent roads to Akbar with the news of his father’s death.

Even as they raced out, in the capital city, the emperor ‘recovered,’ and appeared in view on a balcony. The restive crowd below bent low to perform the salutation of the konish. All they could see of their sovereign was that his recent illness had made him lose. . .height? But his clothes were still splendid and rich, and he kept his face turned away from them, looking out at the River Yamuna.

It was a court poet named Mulla Bekasi, dressed as Humayun. For the moment at least, in this nascent re-established Mughal Empire, held together simply by Humayun’s will, the deception worked.

Akbar at Kalanaur:

A messenger had already been sent right after the fall, fleet-footed, to the guardian, Bairam Khan, chasing down the imperial army on campaign. Bairam had decided that they would wait at the village of Kalanaur. It’s as far northwest as you can get in modern India today, abutting the Pakistani border.

Bairam possibly heard the news of Emperor Humayun’s death on the 11th of February, 1556. Because it was on that day, that the khutba—an official proclamation of sovereignty—was recited at the mosques around Kalanaur, declaring Akbar to be emperor of India.

Emperor Akbar was fourteen years old.

The stone platform on which Emperor Akbar was crowned ruler of the Mughal Empire, on the 15th of February, 1556, in the village of Kalanaur. Image Source.

Four days later, Bairam ratified the khutba by crowning Akbar in that desolate village. He constructed a makeshift stone platform. With as much of the pomp and ceremony as Bairam could muster—the golden robe, a hastily-got-up imperial turban studded with jewels, the abject obeisance of the accompanying army in its generals, its officers, and its men–Akbar was declared emperor of India.

Who’s Bairam Khan then, and why am I dwelling upon him?

Bairam has a whole history, of course, which I’m not going to recount here. Suffice it to say that if he had attained the rank of Khan-i-khanan, Commander-in-chief, he had obviously earned not just Emperor Humayun’s trust, but was eminently capable of leading the imperial armies in Humayun’s quest to retake India.

Another indication of the recently-dead emperor’s faith, was that Akbar, at fourteen, appointed governor of Punjab (most of which was still in foment and not loyal yet to the crown) had been put under Bairam Khan’s supervision.

A closer look at the idealized portrait of the origins of the Mughal Empire. Emperor Humayun, seated, and Bairam, his prime minister, is at his feet, representing the power behind Humayun’s short-lived reign. Image Source.

Now, when Akbar became sovereign, Bairam appointed himself vakil-as-sultanat—which loosely translates into prime minister. But, this title was fraught with other, hidden meanings. Bairam was now regent to the child emperor.

With a young, impressionable king under his charge—one upon whom he already exercised much influence—Bairam Khan intended to be king himself. He had no royal blood and could not claim the throne; perhaps, this was next best.

To do that, Bairam essentially established the beginnings of this embryonic Mughal Empire which was then only a few sections of land, in the Punjab, around Delhi, and the space between the rivers Ganges and Yamuna.

He dragged the young Akbar into a rampage of campaigns, especially to put down all the rebellions that had sprung up once it was known that Humayun was dead, and Akbar far away in the Punjab.

A claimant from the just-defeated Suri ruler put himself on the throne of Delhi. Nobles peeled away to establish their own suzerainty—and Bairam cut them all down ruthlessly.

On a personal level, he taught the young emperor to regard him as a father figure—Akbar called him ‘Khan Baba.’

Remember, Emperor Akbar was only fourteen years old.

The reluctant, aimless ruler of early Mughal India:

If you look back on this slice of Indian history today—through the lens of what the Mughal Empire became, and how Akbar came to be the greatest of the Mughal kings—Akbar’s early, teenage years, filled with a sort of idleness that does not bode any eminence, come as a surprise.

Akbar had been born during his father’s flight from India, and had lived a somewhat nomadic lifestyle. Yet, given his royal lineage, every effort had been made to educate him. And he had escaped from the rigors of every tutor, defying their authority over them.

In consequence, Emperor Akbar was illiterate. Later accounts of his debates and discussions with the ulema (the Muslim scholarly elite) on religion, on religious law, his doubts about Islam, his concept for a new religion, were all verbal, in conversation, because he could not read or write.

Dodging his studies, Akbar had gone hunting tigers and lions. He had shot partridges, fished, and flown hawks. He had played polo on hastily flattened fields with a puck made of palas wood set alight so that he could play at night. (In the third novel of my Taj Trilogy, I’ve set a scene with this game in the dark, played between Princess Jahanara (Akbar’s great-granddaughter) and the man she falls in love with–see Shadow Princess).

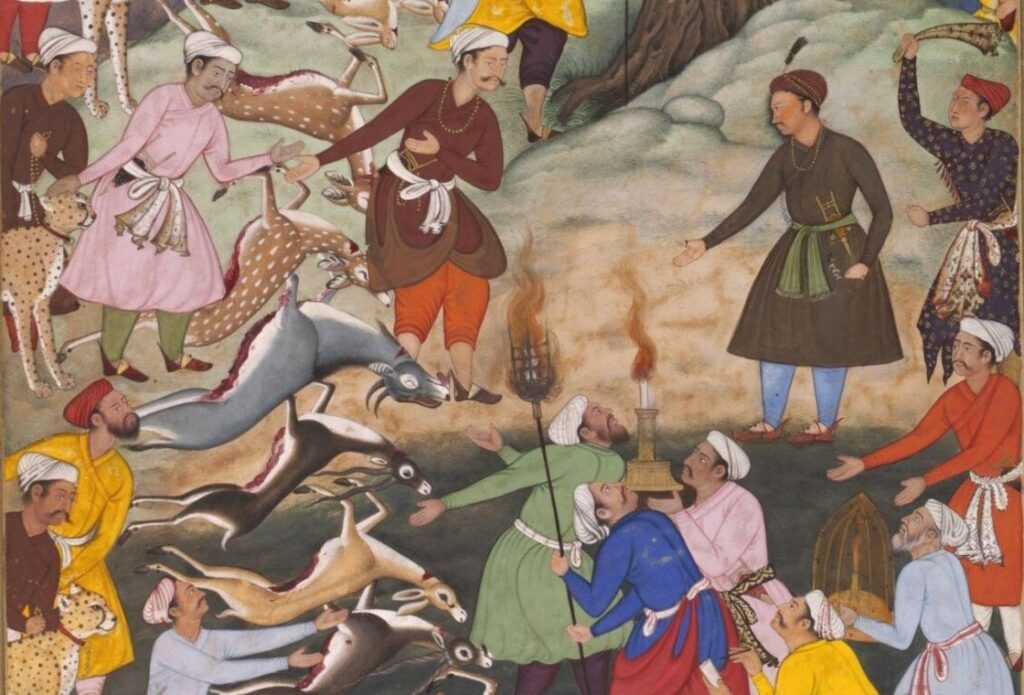

The night was not just for playing polo, as this painting from the 17th Century Akbarnama demonstrates. Here’s Akbar, inspecting a night hunt catch. Again, the details are dynamic in a small canvas—Emperor Akbar, the tame, collared cheetahs, the hunted gazelles and the gray antelope (called a nilgai) and the illumination for the hunt. There’s a torch, a candle in a saucer, and a caged lantern with another light. Image Source.

In other words, Emperor Akbar was a feckless youth, seeking only the pleasures of sport, which made Bairam Khan’s domination over him all too easy.

This Bairam Khan regency in the Mughal Empire—I suppose all positions of absolute power absolutely corrupt—lasted four years. Emperor Akbar was just able to strip himself of Bairam’s hold with the help of the women of his harem—his mother and his wet nurse, Maham Anagha.

He was only eighteen when that happened, and promptly put himself under Maham Anagha’s shadow regency for another two years. So, from within the harem, this woman exerted complete sway over the Mughal Empire.

This is Adham Khan’s tomb in Delhi, and Maham Anagha is said to be buried here, with her son. Both of them came to their inevitable end in a somewhat spectacular manner, and Emperor Akbar built this tomb for them. Only. . . there’s just one sarcophagus in the inner chamber under the dome, so is it Adham or his mother?

We’ll explore that later; Adham’s tomb is a future blog post. Image Source.

I’m often asked how Empress Nur Jahan (married to Akbar’s son, Emperor Jahangir) held such power from behind the walls of the imperial harem in my novels, The Twentieth Wife and The Feast of Roses.

In her case, it’s easy to see; Nur Jahan had the exalted position of a favorite wife—but Maham Angha. . .was not related to Akbar in any way, and was, after all, merely an employee. Not even actually his wet nurse, if some historical accounts are to be believed; merely the superintendent of Akbar’s other two wet nurses.

Akbar and his three wives before he married Maryam:

Emperor Akbar’s first marriage took place when he was about ten years old, and his wife, Ruqayya Sultan Begam, about nine.

It was an arranged marriage—royals in the Mughal Empire had very little choice in wives. In this instance, Akbar had known Ruqayya as a child. She was his uncle (Humayun’s stepbrother) Hindal’s daughter. The two fathers had probably concocted the alliance. Even if that were not true, when Hindal died, his property went to the ten-year-old Akbar. Hindal had also firmly supported Humayun against their other stepbrothers, Kamran and Askari.

Perhaps in gratitude for Hindal’s loyalty, Humayun married his son to Ruqayya.

Akbar and Ruqayya never had children—at least, not living ones, not documented ones. But she was, by far, his most influential wife.

They had grown up in the harem together, and their bond was immovable, no matter how many other wives Akbar took.

When Akbar’s son, Jahangir (born to our Maryam, whose tomb we’re going to visit) had a son with a Hindu wife, Ruqayya asked for the child and reared him, away from his mother. That child, Khurram, went on to become the next emperor, Shah Jahan. More to the point, he built the Taj Mahal, setting the glory of the Mughal Empire firmly entrenched in India’s history.

Ruqayya also mentored Jahangir’s favorite wife in the harem—a young woman named Mehrunnisa, who eventually held the title of Empress Nur Jahan, when she married Jahangir as his twentieth wife (see my The Twentieth Wife and The Feast of Roses).

Emperor Akbar’s second wife, the (first) nameless one:

In 1557, a year into his sovereignty, Emperor Akbar married the daughter of one Abdullah Khan Mughal.

Akbar’s official biographer, Abul Fazl (more on Fazl later, especially when I talk about that mystifying Hindu wife, Jodha) mentions Abdullah Khan Mughal as one of the grandees of the empire. The translator of Fazl’s Ain-i-Akbari, Heinrich Blochmann (more on Blochmann later also in the same context as Fazl) fails to discover details of this Abdullah Mughal’s life.

One fact is known: Abdullah’s sister was married to Prince Kamran—Akbar’s uncle, his father’s stepbrother, and the man somewhat responsible for Emperor Humayun’s exile from India. Humayun defeated Kamran on his way back and had him blinded as punishment.

It’s certainly a telling thing if Abdullah was Kamran’s brother-in-law—his loyalties would have lain toward him, and not Humayun.

Bairam Khan, Akbar’s powerful regent, was said to have been against this marriage, and yet, Akbar married this girl, who was possibly younger than him; Akbar was just fifteen years old.

If Bairam was indeed reluctant to give his consent to this alliance, then, even this early into the regency, Akbar defied him with this decision.

Why did he marry Abdullah’s daughter? It’s likely that Abdullah Khan Mughal was a formidable warrior, who had commanded the loyalty of many armies under Kamran, and so, had enormous influence. And, in 1557, Kamran had just died, after having been sent into exile by Humayun. So, Kamran could no longer exert any control over Abdullah.

Let’s assume a young Emperor Akbar had thought this out carefully. He swayed the allegiance of an experienced soldier by marrying his daughter, brought Abdullah into his family, and shifted his fidelity to his own crown. And Akbar did all this against his regent’s advice?

Then here we see the beginnings of Akbar’s eventual domination over Indian lands, executed with the finesse of a seasoned diplomat.

There’s no documentation on any children from this second marriage.

Emperor Akbar’s surviving children are attributed to Maryam, of course (who gave birth to the next emperor, Jahangir) and concubines.

Bairam Khan marries into the royal family:

In that same year, 1557, Akbar’s regent, Bairam Khan married one of the emperor’s other half-first cousins, Salima Sultan Begam.

Salima was eighteen that year, Bairam Khan was in his fifties.

The common consensus among historians is that Emperor Humayun had promised Bairam this alliance, and that Akbar was only fulfilling his father’s wishes. (In the Mughal courts, all marriages had to be sanctioned by the emperor—since Bairam was regent now—pseudo king—maybe the approval was taken for granted?)

Hearkening back to Akbar’s marriage to Abdullah Khan Mughal’s daughter, and Bairam’s strenuous objection to it. . .it’s just possible that Akbar gave Salima to Bairam to appease him. . .perhaps. It was no mean thing to be connected with the imperial family, and Bairam would have welcomed the suggestion.

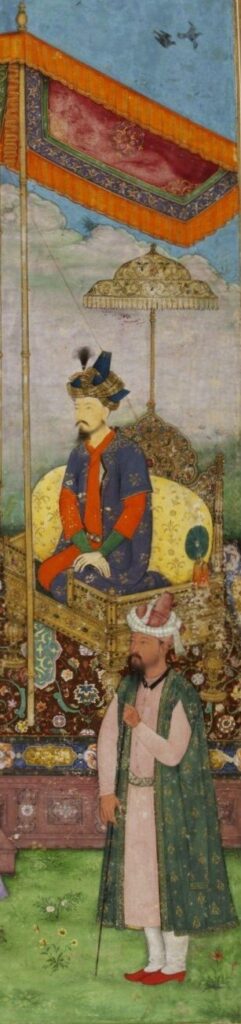

From a painting in the Akbarnama: Bairam Khan’s son, Abdur Rahim, about 4 years old perhaps, being taken to the imperial court after his father’s death. Image Source.

If Bairam and Salima had children, there’s no mention anywhere. One of his sons, Abdur Rahim—born to another wife, would go on to have a long and illustrious career under emperors Akbar and Jahangir. And, like his father, Rahim would also end his career ignominiously.

Why am I dwelling on Salima Sultan Begam? Ah, because she’s Emperor Akbar’s third wife!

Four years later, Akbar had wrenched himself away from Bairam’s regency, and sent him on the Haj to Mecca.

This seems to have been early Mughal policy to get rid of enemies—Emperor Humayun also sent his blinded, disloyal half-brother, Kamran, on the Haj, and he died there. Most men could only undertake it when life slowed down, or retirement came.

It was also an extremely costly, time-consuming affair, this—travel in 16th Century India. In 1575, a section of Emperor Akbar’s harem—his mother, his aunts, even his wife Salima Sultan Begam (I’ll get to how Bairam’s wife becomes Akbar’s wife just below) set out on the Haj.

Women, especially royal women, with their need for the purdah (the veil), their luxuries, their military escorts, naturally travelled much slower than men. But, even for them, the first leg of their trip—to a port in western India—was extraordinarily slow, one whole year from Agra to, presumably, Surat.

There, they had to wait for a Turkish ship—Indian ships were under the control of the Portuguese Jesuits in India. And the Portuguese were tetchy with demands for passes and payments for security from pirates. Delays then, were not merely piracy at sea, becalms, and sluggish trade winds. But there was also the sheer fatigue of having to acquire permits in India and in the Middle East, various supplies, and many lodgings during the journey.

The harem women spent three-and-a-half years abroad and made the Haj four times. On their way back, they were shipwrecked and marooned, until another passing ship picked them up.

All told, their Haj journey took some seven years—they left Agra in 1575 and returned in 1582!

So. . .back to the dispossessed regent:

Bairam Khan also had always cherished a desire for the Haj, and, according to historical record, had spoken of this before, lamenting political duties which left him no time.

Salima Sultan Begam and Bairam’s son, Abdur Rahim, under military escort to the imperial court after Bairam’s assassination in 1561. Painting from the Akbarnama. Image Source.

Now that he had been exiled from the imperial court and his duties as regent by Emperor Akbar, he got his wish.

However, news flew around about the true state of affairs—Bairam had fallen from royal favor. He no longer had imperial protection.

In January of 1561, as Bairam was still a-move in a westerly direction (toward Mecca from India but still very doggedly on Indian soil), he was killed by a man who had a long debt to settle. Bairam had killed his father many years ago.

Emperor Akbar then married Bairam’s widow, Salima Sultan Begam, that same year, 1561. There’s no date for their marriage, but it was within a few months.

Akbar was eighteen, Salima, three years older than him.

Another page from the richly illustrated 16th Century manuscript of the Akbarnama. Bairam was killed at the Sahasralinga Lake at Patan (current-day state of Gujarat; lake is dry today). He had spent the day at the water pavilion in the center of the lake, and toward evening, returned to shore. His assassin was most likely the Afghan Mubarak Khan Lohani—but there were other Afghans thirsting for his blood. Image Source.

So, two of Emperor Akbar’s (early) wives were related to him—Ruqayya and Salima:

This wasn’t at all an uncommon policy for the early Mughals—Akbar’s grandfather, Emperor Babur, had married several women who were associated with him and his Miran-Shahi family.

(The Mughal kings had impressive lineages, connected to both Timur the Lame, and Chengiz Khan the Mongol. One thing: Timur’s son was one Jalaluddin Miran Shahi, did nothing much himself, but gave descent to the Emperor Babur six generations later. Another thing: As much as the Mughals tried to distance themselves from their Mongol ancestry and extend toward their more sophisticated Turkish progenitor—Timur—their very name, ‘Mughal,’ is a corruption of the word, ‘Mongol.’)

Both Ruqayya and Salima were Emperor Akbar’s half-first cousins.

Ruqayya’s father, Hindal, and Salima’s mother—let me leave a space here for the mother’s name and explain below—were direct brother and sister. Both were born to the same mother, Emperor Babur’s wife, Dildar Begam.

Akbar’s father, Humayun, was born to another of Emperor Babur’s wives—Mahim Begam.

What’s the mystery about Salima Sultan Begam’s history?

Abul Fazl (Akbar’s biographer; author of the Akbarnama) asserts very confidently that Salima was the daughter of one of two women—Gulrukh in one reading of his Persian text; Gulbarg in another.

Fazl at least got the ‘Gul’ prefix right. Because Emperor Babur’s wife, Dildar Begam, had three daughters with that same ‘Gul’ or ‘rose’ prefix—Gul-rang (rose-hued); Gul-chiran (rose-cheeked) and Gul-badan (rose-bodied).

Gulbadan could not have been Salima’s mother—she was the author of Akbar’s father, Emperor Humayun’s biography, the Humayunama, and would doubtless have mentioned this fact.

Salima was her niece, the daughter of one of the two other sisters, either Gulrang or Gulchiran.

A closeup of the painting from the Akbarnama. That’s Salima in the palanquin. Curiously enough, no other woman is portrayed in this illustration—the omission is especially obvious in the case of that other wife of Bairam’s, Abdur Rahim’s mother. She’s not there. Emperor Akbar took care of the boy, Abdur Rahim. But, Salima, obviously, was more important than Rahim’s mother. Image Source.

History’s unkind to women; no matter how powerful they are, or what they achieve, they become very often footnotes to men’s accomplishments. Perhaps especially so far back, in the 16th Century in India.

And so, while there’s a doubt as to who Salima’s (royal) mother is, her father’s name is documented—he was a Mirza Nuruddin Muhammad Chaqaniani. Only, no one’s quite clear whether Gulrang or Gulchiran married him and begat Salima.

Salima Sultan Begam’s influence over Akbar:

We’re still at a point in Emperor Akbar’s life—in 1561 when he married Salima, he was nineteen years old—where he’s well within Islamic law in taking a wife. He was allowed a maximum of four wives, and she was his third. (That changed later on; Akbar married several more wives.)

The most common reason historians give for Akbar marrying Salima when Bairam Khan died, is that he wanted to provide her with a home.

It’s certainly possible—just as Ruqayya grew up (more or less) in the harem with Akbar when he was young, Salima was also probably an inhabitant of the same space. He would have known her as a child, played with her, and had a chance for increasing his affection for her.

But he did not need to marry her—she could very well have come back into (what is now) his harem and have lived there for the rest of her life, under his protection and shelter.

If he was allowed only four wives—why waste one marriage where he gained no diplomatic influence or connection with a powerful noble’s family at court? I’m guessing that Salima meant more to Akbar.

And so, Salima became Emperor Akbar’s third wife. They had no children. One historian (I’ve only found one historian who says this) asserts that one of Akbar’s other sons, Murad, was born of Salima, but it’s quite clear that Murad was born to a concubine.

So, childless, and without the only factor that gave a woman power within the walls of a Mughal harem—the bearing of a male child—Salima still became hugely influential over her second husband.

She was a highly educated woman (remember, Emperor Akbar was essentially illiterate), wrote poetry under the pseudonym of Makfi (concealed), collected books, and had a vast library within the harem.

As I mentioned before, she convinced Akbar to allow her to go on the Haj to Mecca with her aunt, Gulbadan, her step-aunt and Akbar’s mother, Hamida Banu Begam, and other ladies of the imperial harem in 1575—and, they were away for seven years.

This, the permission to be away for so long, was a big ask. Akbar had perhaps little control over his mother or his aunts, but over his wife, he certainly had. And, he agreed to let Salima go.

Salima exerts her voice and her might:

In later years, Salima played two very important and well-documented roles of diplomacy within the royal family.

In 1602, Emperor Jahangir (Akbar’s son and heir, at that time Prince Salim) rebelled against his father and had Abul Fazl murdered—yup, that Fazl who was the author of the Akbarnama and Emperor Akbar’s dear friend and confidant.

Akbar was naturally enraged at this unfilial and inhumane conduct. A year later, it was Salima who brought forth a reconciliation between father and son. She went to Allahabad where Salim had set up a mock-court within his father’s empire, slapped him around (I think!) and brought him back to Agra to beg forgiveness from Akbar.

Prince Salim, in establishing himself ‘Sultan Salim Shah’ at Allahabad while defying his father, had this black slate platform commissioned as a throne. It’s on display at Agra Fort today, with, of course, that obligatory view of the Taj (built much later) along a bend in the Yamuna River.

A few years later, possibly in 1605, when Jahangir had finally stepped on the throne of the empire upon his father’s death, he set about punishing all the nobles who had vigorously or passively resisted his ascension.

One of those was a Mirza Aziz Koka, who had indeed very actively championed Jahangir’s son for the throne.

The thing was, the nobleman, by the suffix of his very name ‘Koka,’ was Emperor Akbar’s foster brother. Koka’s mother had been one of Akbar’s wet nurses. He had grown up in the harem as Akbar’s brother, and consequently had also known Akbar’s cousin-wives, Ruqayya and Salima.

So, at one of Emperor Jahangir’s first audiences as king, as he was about to pronounce Koka’s fate, our Salima (Jahangir’s stepmother) shouted out from behind the screen that partitioned the harem women from the court. Something to the effect of, you’d better come into the harem enclosure and talk this out with us, or we’re coming out there into open court!

The simple marble screen on either side of the throne balcony at Agra Fort, behind which the women of the harem watched the proceedings. And, spoke out, as Salima did on this memorable occasion.

Jahangir rose from his throne in a great hurry. He knew Salima well enough by now to be sure she would make good her threat.

The result was that Mirza Aziz Koka kept his neck, and his life, although he did lose his rank and his wealth.

(Both the Fazl murder and the Koka incident are in the first novel of my Taj Trilogy, The Twentieth Wife.)

And now, that we’re done with the first three wives, we’ll visit that fourth wife, Maryam, on the next instalment.

If you’ve enjoyed reading this post, please share it, so others may read also. Thank you!

Keyword phrases: Is Jodha Akbar story real; Jodha Akbar real story; Mughal Emperor Akbar; Emperor Akbar’s tomb; Akbar the Great; Mughal harem; Mughal Empire in India; where was the Mughal Empire; Akbar’s wife.

Primary Sources: Henry Beveridge, trans., The Akbarnama of Abul Fazl, 2 volumes; Heinrich Blochmann, trans., The Ain-i-Akbari by Abul Fazl Allami; Lieutenant-Colonel James Tod, Annals and Antiquities of Rajasthan, 3 volumes; Vincent Arthur Smith, Akbar the Great Mogul, 1542-1605; Pringle Kennedy, A History of the Great Moghuls; Henry Beveridge, trans., and Beni Prasad, The Maathir-ul-umra; George Ranking, trans., Munktakhab-t-Tawarikh by Al-Badaoni; Rima Hooja, A History of Rajasthan; B. DE, trans., The Tabaqat-i-Akbari of Khwaja Nizamuddin Ahmad; William Henry Sleeman, Rambles and Recollections of an Indian Official; Beveridge, Henry, article in Journal of the Asiatic Society of Bengal, Volume LVI.

On the next blog post–we meet that fourth, and most important wife–Maryam’s tomb. Two of Emperor Akbar’s wives–The mysterious Maryam and the elusive Jodha–Part 2

“Maryam’s Tomb” is a thoroughly engaging and interesting reading. During my student years, the study of history was onerous and tedious. The way the author describes persons of history and the historical facts makes history so palatable and deeply interesting. Mulla Bekasi’s trick, Bairam Khan’s role in Akbar’s reign, and the fact that Akbar was an “illiterate” who could neither read nor write (early in life, at least) were relatively unknown facts but worth knowing. The author’s brief introduction in the beginning is done well.

The way Indu Sundaresan has moved from Appomattox Court to Akbar’s Empire establishes her innate love for history. She will undoubtedly treat all history, whether it relates to Greece, Rome, or Persia, with the same passion. Hats off to you, Indu.

Thank you so much!!

A fantastic and enjoyable reading. Eagerly wating for next part.

Thanks n warm regards

Thank you!