On the first part of this blog post, we tarried our way through the origins of the Mughal Empire until Emperor Akbar had married his first three wives. He’s now poised to make his fourth marriage with a Hindu princess—a first of many firsts, you’ll see why.

This empress, later given the title of Maryam Muzzamani, and bestowed with a tomb that we are going to visit, would give birth to the first of Akbar’s surviving sons—finally, an heir for Akbar’s empire.

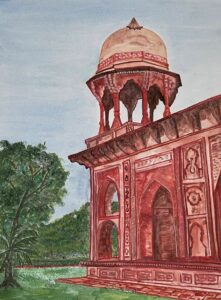

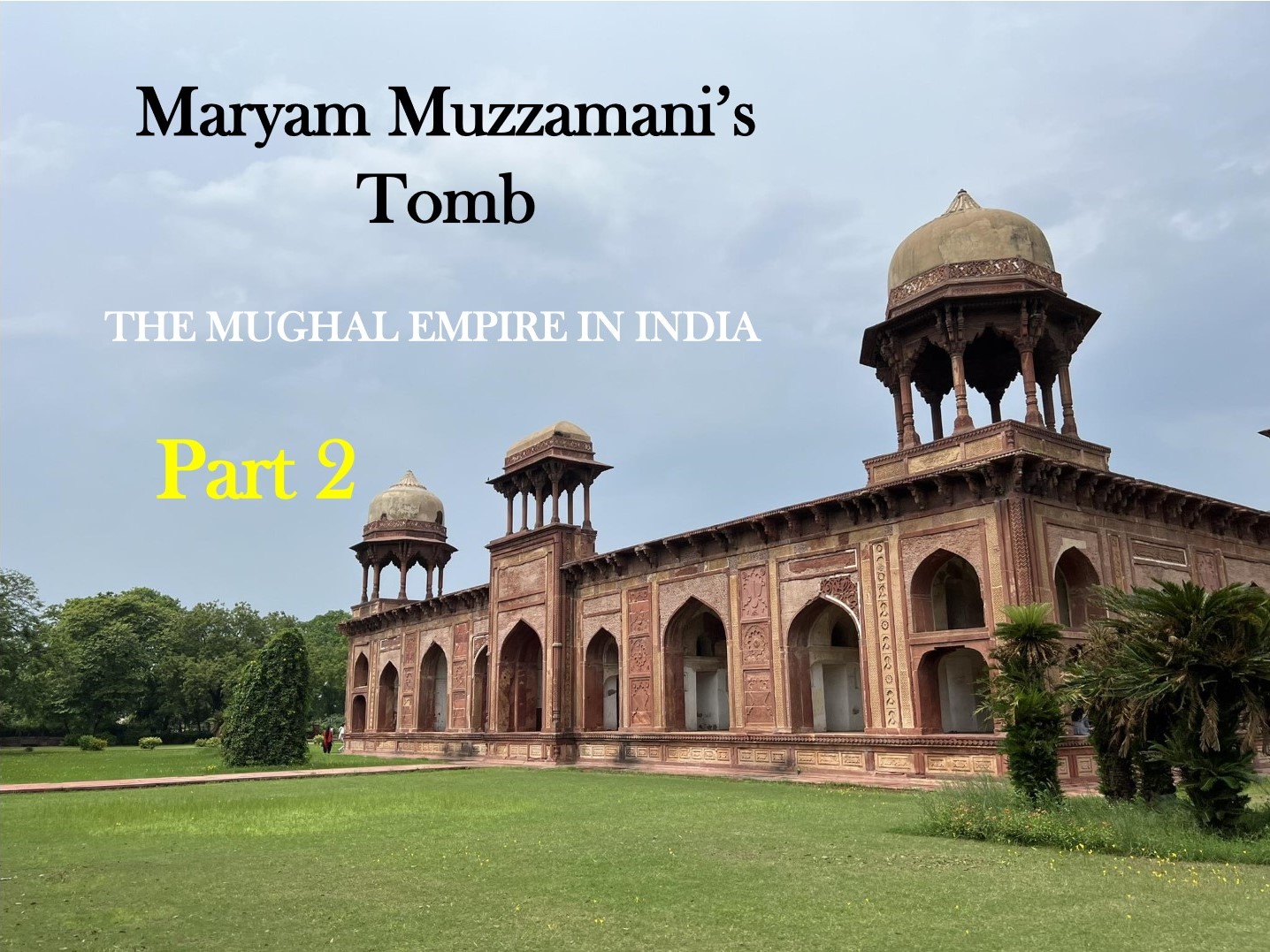

Maryam Muzzamani’s tomb at Sikandara, near Agra.

When that son, Prince Salim/later Emperor Jahangir, was born, Emperor Akbar had achieved the grand old age of twenty-seven years. But, his anguish was legitimate. He had several wives by then—how many it’s not quite clear, maybe six or seven, because they are not adequately documented in the histories. He had also had several children, but none had survived and Akbar’s empire was without an heir.

In Part 1, we saw Emperor Akbar marry his first three wives, in this; Part 2, we’re going to meet wife number four, who, in 1569, gave birth to Prince Salim.

At Salim’s birth, when Emperor Akbar was twenty-seven years old, he had already been married for seventeen years—yes, you read that right, Akbar’s first marriage was when he was ten years old.

Maryam Muzzamani steps backstage:

Akbar married Maryam in 1562; he was nineteen, and she was probably just a bit younger than him. Maybe. Perhaps.

Because there’s literally nothing more we know about her other the fact that this princess married Akbar in that year.

How old was she? What did she look like? Was she pretty? Insipid? Intelligent? No one knows. (Well, there’s no information from 1562, but later in life Maryam proved to be a shrewd and powerful trader and negotiator from behind the harem walls.)

But, the most astounding fact is that even her name—I mean her original name, her Hindu name, if you will, the name given to her at birth—has not survived in historical documentation.

She is only known today by the title that Emperor Akbar gave her seven years after their marriage when, in 1569, she gave birth to Prince Salim in the tiny village of Sikri, some twenty miles southwest of Taj-famous Agra.

At that event, a grateful Akbar bequeathed upon her the title of Maryam Muzzamani—translated as ‘Mary of the Universe.’ And her birth name slipped out of usage and into oblivion. Emperor Akbar’s own mother carried the title of Maryam Makani—Mary of the World, and so he probably wanted to honor his wife as his mother had been honored by his father.

So. . .Emperor Akbar had a Christian wife then?

Mary or Maryam/Mariam is very much the name of the mother of Jesus. Why did both Akbar and his father, Humayun, use it for a title for their wives? Because Mary is one of three women exalted in Islam, the other two being Khadija, wife of the Prophet Muhammad, and Fatima, their daughter.

In later centuries, travelers and historians writing about Maryam Muzzamani’s tomb at Sikandara, mistook her, by her name, for a Christian wife of Emperor Akbar’s. They thought she was either Armenian or more likely, Portuguese—the natives of both countries had established large populations in Akbar’s empire.

But, Emperor Akbar had no Christian wife.

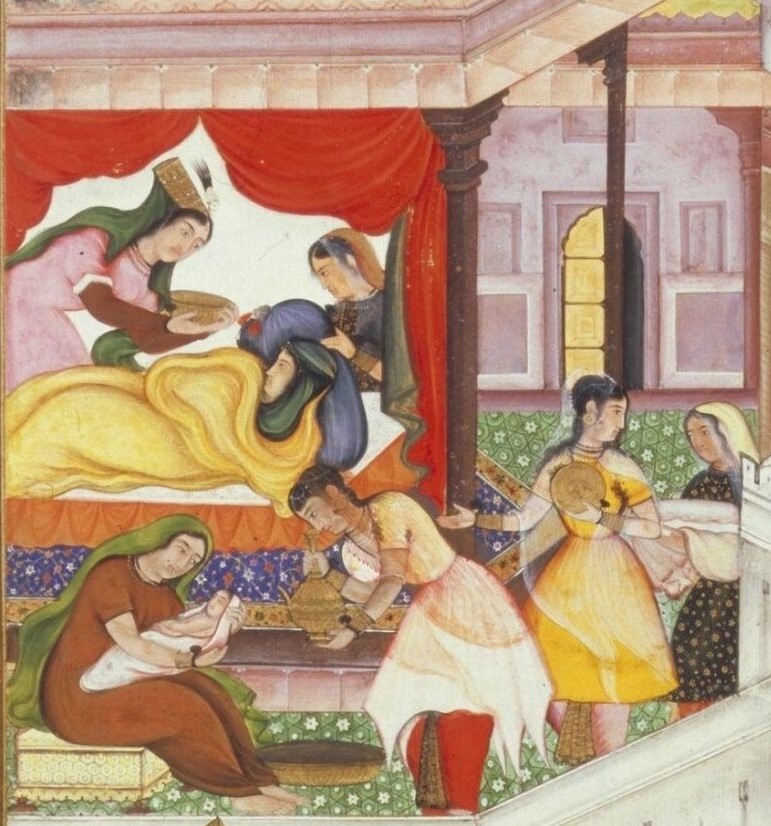

There’s no painting or depiction of Maryam Muzzamani extant, or at least, not known. But several paintings purport to be of her. This is one of a set of paintings broadly categorized as being of ‘Mughal ladies and princesses.’ At the very least, we get a glimpse into the general demeanor of a royal queen in Akbar’s empire—in the clothing, the rich fabric of her outfit, the Kashmiri shawl draped over her left shoulder, and the splendid pearls, rubies and emeralds in her jewelry. Image Source

And here, in a first of firsts, a Hindu princess married the Islamic emperor of India’s Mughal Empire. Maryam was the first, but by no means the last—Akbar himself had at least two more Hindu wives.

His son, Emperor Jahangir, married Hindu and Muslim women with abandon, knowing the value of these alliances, until he came to that last and twentieth wife he truly loved, whom he called Empress Nur Jahan.

(Nur Jahan is the main protagonist in the first novel of my Taj Trilogy, titled. . .what else? The Twentieth Wife).

A glimpse of a bride’s life in the imperial Mughal harem:

All marriages in medieval India, in and around the court, either with the royal family or within the nobility, were carefully curated. The most important considerations were familial influence, power, authority and prominence. Love had little to do with it. The two main players did not even see each other before they were married, and the woman was said to have entered the man’s harem upon marriage.

This was true of both the Muslims and Hindus in Mughal India.

During the wedding ceremony, the bride would be veiled, and so would have a minor advantage over the groom who could not see her face. If she squinted behind the fabric, the embroidery, and the slender garlands of flowers shrouding her, perhaps. . .she could see him.

After the ceremony, she would be sent into the harem. There, the new bride would begin launching relationships, with her peers (other wives), her elders (her husband’s mother and stepmothers), and those below her in rank (her husband’s cousins, sisters, and other female relations).

When would she see her husband? There was no knowing. It depended on how interested he had been in the marriage.

The rapport with the other ladies then became very important to the bride.

Life in the imperial Mughal harem was beyond luxurious. Vast apartments, pools and fountains for coolness on hot nights, attendants galore to tend to every need. In this picture, one lady lazes with a hukkah in her hand, listening to music. Another dips her feet into a pool. A third puts her arm companionably around two servants.

In this city of women, navigating interactions with other women with dexterity was paramount to a newcomer—it gained her some peace of mind, of course, but also power and authority. Image Source

Akbar’s grandfather, Emperor Babur—the man who established the Mughal Empire in India—is candid about his first marriage in his memoir, The Baburnama. He married his first cousin (father’s brother’s daughter) Ayisha Sultan Begam, when he was sixteen years old. They had been betrothed since he was five.

He initially visited her only every ten, fifteen, or twenty days. His mother hauled him up for neglecting his marital duties, and he tried to go more often. It didn’t work. Eventually, once a month or every forty days, through ‘driving and driving, dunnings and worryings,’ his mother forced him upon his wife’s presence.

The inevitable result was that Ayisha ended up having her first child some three years into the marriage. And then, at some point, she left Babur—and forced him to divorce her.

Babur later married one of Ayisha’s sisters, Masuma Sultan Begam, but he had seen her before, and asked for her hand in marriage. Masuma stayed in her marriage, doubtless, having received more attention from Babur than her sister had.

Who’s Maryam then, and why did Akbar marry her?

Islamic law allowed four wives, and Akbar, as we know, was already possessed of three when Maryam came into his harem. In a matter of course, Emperor Akbar married more wives, and circumvented the law by picking and choosing what he liked in conversations with the ulema (Islamic scholars), and, giving many of his women the nikah (fixed marriage) status within his harem. (We’ll visit Emperor Akbar’s magnificent tomb at Sikandara in a future blog post, and I’ll delve deeper into these conversations then).

Akbar’s Mughal Empire, that he inherited upon his father’s death in 1556, was a fraction in real estate to what it became when Akbar died after ruling for some fifty years.

Given the time period, the difficulty of travel, the very vastness of Akbar’s empire, the one way in which he maintained control and fealty in his lands was by contracting marriages with the daughters, sisters, and cousins of the kings he conquered.

What did they get out of it?

Well, it was their advantage to remain loyal to him, as long as there was the slightest chance that a child born to one of their women would become the next emperor.

Despite a royal prerogative to rule, a divine right from heaven, and a protective army on earth, even Emperor Akbar was not exempt from an attempt at his life. And, this happened almost directly as a result of his policy toward marriage. This was in 1561, the year before Akbar married Maryam. Akbar had just brought another man’s wife into his harem in a mutah (temporary) marriage, by the simple expedient of mentioning the matter to Shaikh Badal, her father-in-law. And then, instigated by his regent wet nurse, Maham Angha, he had sent out a general invitation to other nobles in Delhi to present their daughters to him.

His prospective assassin was a slave named Fulad, who shot an arrow at the emperor from the terrace of a madrasa (school) that Maham Angha had constructed in Delhi. The arrow pierced the emperor’s shoulder, Akbar’s aides extracted it, two physicians applied a poultice of monkshood as an anesthetic, and the wound scarred over in about a week. Akbar rescinded his order to the nobles following this assassination attempt. Perhaps that’s why he next married Maryam, not from his court, but from a Rajput family?

The painting shows the incident—Emperor Akbar holding the arrow which had injured him, and poor Fulad (probably a paid assassin) slaughtered by the accompanying soldiers at bottom left. Image Source

And so it was with Maryam, the first Hindu princess to set foot into an imperial Mughal harem.

In later years, Maryam Muzzamani—when her son Emperor Jahangir sat on the throne of the empire—was enormously powerful and extremely rich. She had a large income from the imperial treasury, owned several estates around the empire, appointed stewards to manage them, and had a fleet of ships that traded the Arabian Sea routes and took pilgrims to Mecca and Medina.

She built gardens and sarais–rest houses–along the network of highways in the empire, and left her stamp on history in legend and in stone.

But, who was she?

Raja Bihari Mal steps on stage:

Maryam Muzzamani was the daughter of Raja Bihari Mal of Amber (I would pronounce it um-bay-r but it’s also spelt as Amer, so maybe it’s uh-may-r?). Today, the kingdom does not exist—it’s the area around the city of Jaipur in the state of Rajasthan.

And, just north of Jaipur is the fort of Amber built by Bihari Mal’s grandson, Raja Man Singh, who was an integral part of Akbar’s empire, formidable and well-respected.

Raja Man Singh began constructing Amber Fort during his long and lucrative residency in Akbar’s empire. Even though Emperor Jahangir was his first cousin, and also married to his sister, by the time Jahangir came to the throne, he’d been disloyal to him. And so, Man Singh’s influence waned during Jahangir’s rule. Image Source

Man Singh was Raja Bihari Mal’s grandson, and so Emperor Akbar’s wife’s nephew, and Emperor Jahangir’s first cousin. And, incidentally, Emperor Jahangir’s brother-in-law, and uncle to Jahangir’s son, Prince Khusrau.

Do you see the generations of advantages that the one marriage between Akbar and Maryam achieved for Raja Bihari Mal’s family?

So, who was Raja Bihari Mal then?

If we go way back into the history of Maryam’s family, we’ll have to retreat to about 400 BCE, and the Hindu epic, the Ramayana. (Everything’s connected in Indian history, truly, and I spoke a bit about the story of this great poem in my blog post about the Airavateshwar Temple in South India).

By the end of the Ramayana, Rama’s wife, Sita, in exile, gives birth to twin sons, Luva and Kusha.

Raja Bihari Mal’s clan of the Kachhwaha Rajputs laid claim to ancestry from Kusha. As in, over the centuries, Kusha’s descendants moved to northwest India and the current-day state of Rajasthan.

Closer to Bihari Mal, one Dulha Rai (late 10th/early 11th Century depending on the historian) was persuaded by his father-in-law to move from his hometown of Gwalior to the Amber area (to a town called Dausa) by the simple expedient of giving him the town as part of his dowry. Dulha Rai was a nickname—‘dulha’ means bridegroom and supposedly this young man was blessed with a certain level of physical beauty.

But, he also had a strong hand upon his sword. Half of Dausa, his dowry, was in the possession of another chieftain—his father-in-law had only given him the other half. So, he set about routing that chieftain, and then turned his gaze thirty miles westward to the area around the current city of Jaipur.

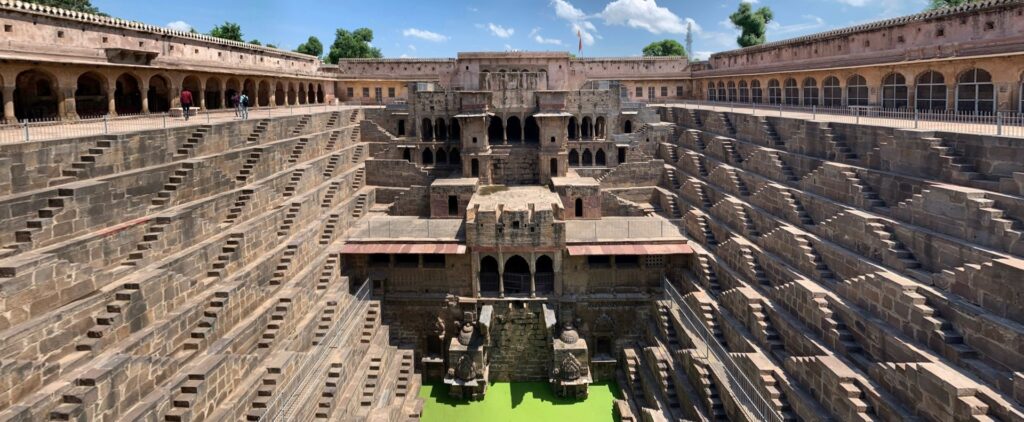

Dulha Rai left no trace of himself at Dausa—he had other places to go. But close to the town is a spectacular 9th Century stepwell, a hundred feet deep, with thirteen stories and a temple within, called the Chand Baori. Image Source

Jaipur/Amber then, was ruled by a clan of Meena chieftains whom Dulha defeated. Long tradition has it that as part of the treaty Dulha made with the Meena chiefs, every new Kachhwaha Amber king, during his coronation, would be anointed with the ‘raj tilak,’ the vermillion mark on his forehead, by someone of the Meena clan. And so it was, for a while at least.

Three centuries or so later, Raja Bihari Mal’s father, Prithviraj, was king of Amber. He died in 1527—a year after Akbar’s grandfather, Emperor Babur, had established the Mughal Empire.

Prithviraj was certainly not a Mughal vassal. In 1527, just before he died, he fought alongside another Rajput king against Babur and they were defeated.

Raja Bihari Mal’s long, long, looong trek to the Amber throne:

It was another twenty years before Raja Bihari Mal came to rule over Amber, and by then, it was perhaps because there was no one else left.

So let me try to encapsulate those twenty, torrid years in as short a space, so you can understand the fluidity of loyalties and the sheer dangers associated with being part of a ruling family in Rajput kingdoms during that time.

At his death in 1527, Prithviraj had designated a younger son, Purna Mal, for the throne, since Puran’s mother was his favorite wife. Cherchez la femme? As an aside, there’s one theory that Akbar’s father, Emperor Humayun (not emperor until 1530, but heir-apparent to the Mughal Empire) had supported Puran Mal’s ascendency.

If this is true. . .then it’s the first, and very early alliance of sorts between a Rajput king and the Mughals, because Humayun wouldn’t have lent his weight to Puran Mal for nothing.

Anyhow, Bhim Singh, the dispossessed eldest son, naturally took affront and had Puran Mal assassinated. Bhim then ruled for another four short years, and his son, Ratan Singh became ruler of Amber.

What’s Bihari Mal doing about now?

Remember, Bihari Mal was also Prithviraj’s son—some younger son. While his nephew, Ratan, headed Amber, he was in charge of the province of Sanganer, just south of Jaipur/Amber.

Ratan ruled for ten years, at the end of which, predictably, one of his half-brothers poisoned him. The half-brother then sat on the throne for a grand total of sixteen days.

The nobles at court, disillusioned and frustrated by all this infighting, deposed the half-brother and went to Bihari Mal, with the kingdom as a gift.

And so, in his fifties, in 1548, Raja Bihari Mal finally came to sit on his father’s throne. (A reminder since we’re following parallels with the Mughals: Akbar’s turn had not yet come in 1548; in fact, his father, Emperor Humayun, was in still in exile, and didn’t return to re-establish the empire until 1555).

And then, because he was a wise man, or his many years had given him wisdom, Bihari Mal set about making alliances with Hindu Rajput kings, and with the Muslim generals who had served under the kings of Delhi who had driven Humayun out of India.

Raja Bihari Mal employs diplomacy to keep his just-acquired kingdom of Amber safe:

Read the history of that time period, you begin to realize that there was very little cohesion in northern India, not even in Akbar’s empire when he married Maryam.

When Babur established the empire, he defeated the Delhi Sultan, and so his realm was mostly around the city. Even Emperor Humayun ruled over real estate that was split into different provinces, each with its governor who nominally bowed to the emperor at Delhi. When Humayun was driven out, an Afghan noble came to occupy the throne of this ‘India.’

But there was no certain way of ruling over vast lands, only a hope that your representatives would not set themselves up as sovereigns. For that, you needed strong relationships. Even minor kings—like Raja Bihari Mal—realized this.

Raja Bihari Mal fell into an alliance with a Muslim general, Haji Khan Pathan, who had been a slave under the Delhi Sultan Sher Shah Suri, and had established his own fiefdom on the region he had been given to govern.

In the terms of this contract—presumably so that Haji Khan would not attack Amber—Raja Bihari Mal agreed to assist Haji Khan with an army.

Emperor Humayun came back to India in 1555 and then died six months later, with Emperor Akbar, fourteen years old, and campaigning at a distance from Delhi in northwest India. In that shuffle and uncertainty, Haji Khan decided to attack a Mughal governor nearby and confiscate his lands. Bihari Mal assisted him.

That governor, Majnun Khan, was put under house arrest after his defeat, but a twitchy Haji Khan wanted to kill him. Bihari Mal intervened and had Majnun sent to the royal court at Delhi, thereby saving his life.

The fifteen-year-old Emperor Akbar meets his future father-in-law for the first time:

A year after his coronation, in 1556, when Emperor Akbar was in residence at Agra, a grateful Majnun put a word in his sovereign’s ear, and Raja Bihari Mal was invited to the court to be introduced to Akbar.

This was their first meeting, and Bihari Mal must have sworn fealty to Akbar at that time—quite possibly, he was the first Rajput king to do so. In time, of course, when Akbar’s empire expanded, and the whole of Rajasthan came under Mughal rule, several Rajput kings and chieftains played defining roles in this part of India’s history under the Mughals.

There’s a quaint little story attached to this first meeting between Raja Bihari Mal and his future son-in-law.

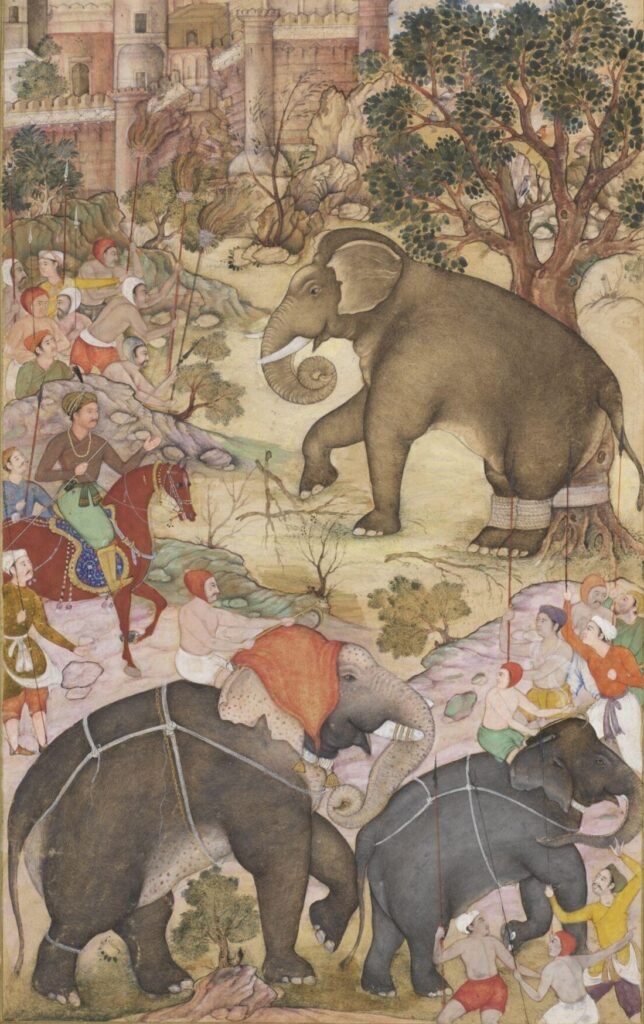

Emperor Akbar was seated on an elephant, and the elephant became mast (wild, agitated) and lumbered about dangerously.

The Mughal soldiers guarding the emperor ran away in fright; it was Bihari Mal’s men who stood their ground and brought the beast under control. They’d had far more experience with elephants—as pets, as pack animals, as transport, and on the battlefield—than their Mughal counterparts.

And. . .that was it.

The wonderfully illustrated 17th Century manuscript of the Akbarnama is a detailed snapshot of life in Akbar’s empire. Here, keepers have captured a wild elephant—tethered to the tree, and Akbar is inspecting it. The two other elephants being led away are already part of the royal stables. Abul Fazl, the author of the Akbarnama, then goes on to outline all the steps that need to be taken in breaking the elephant’s spirit. Check out the beatific expressions of the tame elephants, and the brow raised in anger on the wild one! Image Source

Raja Bihari Mal went back to Amber, and Emperor Akbar’s hand went back on his sword to expand his empire. He continued on campaign with his regent, Bairam Khan, to quell rebellions and conquer more lands.

1562: That second, and pivotal meeting, that enshrined the splendid fate of the Amber kings in Akbar’s empire:

On the 14th of January, 1562, the thrice-wed Emperor Akbar left Delhi on horseback to pay his respects at Shaikh Muinuddin Chisti’s tomb in Ajmer—a distance of about 300 miles. To get to Ajmer, Akbar would have to pass by Raja Bihari Mal’s kingdom of Amber.

Chisti was a Sufi saint in the 13th Century, who had immigrated to India, amassed a large following and died at Ajmer. Emperor Babur, during the four short years that he ruled over India, had encouraged the ladies of his family to make a holy expedition to the Shaikh’s tomb.

Emperor Akbar praying at Shaikh Muinuddin Chisti’s dargah at Ajmer. Image Source

Now, Akbar set off on a pilgrimage of his own. Since he was traveling fast, he instructed Maham Anagha—his erstwhile wet nurse (sort of) and his current shadow regent—to escort the ladies of his harem to Ajmer in a more leisurely fashion.

A journey of three hundred miles, even on horseback, was a months-long affair.

Akbar may have been more fleet than his harem ladies, but at every stop for the night, silken tents were laid out for him, he slept on feather mattresses with velvet cushions, his food was cooked by a battalion of chefs, and came served under gold and silver covers.

On one such halt, an intimate called Chagatai Khan came to his emperor with the tale of Raja Bihari Mal’s woes.

What had happened to our good Raja Bihari Mal in the last six years?

Akbar’s empire was still in its infancy, and did not yet have that splendid administrative system in place with checks and balances against his governors’ petty tyrannies. He had other problems too—he had just wrestled out from under his regent, Bairam Khan’s heavy-handed rule, and then put himself promptly under his wet-nurse, Maham Anagha’s thumb.

The governor of the province that Akbar was traveling through, which included Amber (the future Jaipur) and Ajmer (where Akbar was headed), was a Mirza Sharifuddin. This man had turned a covetous eye over Raja Bihari Mal’s capital city (at the time it was still Dausa) and sniffed around a bit.

What turned Sharifuddin into a conqueror was that Raja Bihari Mal’s nephew, who thought he had a claim to the throne, went to Sharifuddin and encouraged him to attack.

There was no battle, however.

Raja Bihari Mal knew he could not defeat the governor’s army, so he fled from Dausa and took refuge in the hills. He also had to send his son and two nephews to Sharifuddin as a surety against further rebellion.

This, was the state of affairs when Akbar’s minister bent to tell him the story.

As an aside, if you remember, it was another Mughal governor who had first introduced Bihari Mal to Akbar, four years ago. Now, it was a courtier who took up his cause.

It’s testament to Bihari Mal’s diplomatic skills, and also his wisdom in recognizing that the Mughals were here to stay, and that if he could not fight the emperor, he ought to join him.

And, when Bihari Mal had first met Akbar, he had paid his obeisances to him, and accepted him as sovereign. Now, he had fallen prey to the rogue governor Sharifuddin.

We’re diplomats, all:

The nineteen-year-old Emperor Akbar was outraged at Sharifuddin’s behavior. He would answer for his crimes. As a first step, Akbar sent for members of Raja Bihari Mal’s family.

Raja Bihari Mal then came out of hiding to ‘kiss the threshold’ of the imperial presence.

His Majesty with his discerning glance read devotion and sincerity in the behavior of the Rajah and his relatives.

–from The Akbarnama by Abul Fazl.

Bihari Mal reasserted his loyalty to the crown, flung his life into the emperor’s service, and was incalculably grateful for the condescension shown to him by His Majesty the Shahenshah. (Shah-in-shah—king of kings).

(Read enough of the lavish language of the Akbarnama, and I begin writing like it!)

Akbar was gracious and gave him back his kingdom of Amber.

Ummm. . .I have a daughter, a very pretty one:

At this point, at least according to the Akbarnama, Raja Bihari Mal offered up his ‘eldest’ daughter in marriage to Emperor Akbar.

That ‘eldest’ is a highly suspect word. Bihari Mal was crowned king of Amber in 1548 and he was in his fifties by then. It’s improbable that he had had no daughters, and if he had, the eldest would have been in her late thirties at least.

As I mentioned, by this time in India’s history, both the Muslims and the Hindus kept harems, and married several times. So most likely, the daughter who Bihari Mal proffered to Akbar, was born of one of his much younger wives, and could not have been more than say. . .fifteen or sixteen years old.

Why did Emperor Akbar accept Maryam?

We’re now in 1562. In 1561, Akbar had married for the third time. The lady, Salima Sultan Begam (See Part 1 of this blog post) was his first half-cousin, and widow of his erstwhile regent, Bairam Khan. With this marriage, Akbar had arrived at the third of his four permitted marriages.

Now, in 1562, he was poised to make his fourth marriage. By all rights, he probably thought it would be his final marriage, but, he went on to marry several more times, and to demand a legitimate nikah status for all his wives. (More on this, when I do a future blog post on Emperor Akbar’s tomb at Sikandara).

I only mention the importance of the final marriage for Akbar, because it is something he would have thought about in very practical terms.

What advantages did Maryam bring to him? Family support? Were they powerful enough to warrant an alliance with the imperial Mughal family? Could they be of future help as he expanded the boundaries of his empire?

They were Hindu, and Rajputs, what sort of standing did Bihari Mal have among other Rajputs? Especially ones not yet under Mughal yoke? Did they respect him? Would they follow his advice and swear obedience to Mughal interest?

I’m also a little suspicious of Abul Fazl’s assertion in the Akbarnama that Raja Bihari Mal was the one who proposed the marriage.

If you understand the workings of royalty and the imperial Mughal court, it’s a proposition that Bihari Mal—grateful anew to Akbar—would not have dared to make. What, come up to the King of Kings and say, marry my daughter? I think Akbar made the suggestion first.

So, here’s a nineteen-year-old sovereign, who had had a wasted youth, never learned to read or write, was kept under the suppression of a regent, and is right now oppressed by a woman in his imperial harem, making a choice that would have tested the competence of the most experienced consul.

It was the right decision. The Rajput kings—vast in scattered kingdoms—had to be conquered. Their fidelity was crucial to the existence of Akbar’s empire. Raja Bihari Mal had already shown himself to be dependable. With this first alliance into a Rajput family, Akbar was setting up a long chain of Rajput allegiance.

And, perhaps more importantly for Akbar, his current ruler—Maham Anagha, his once wet nurse—had not yet arrived with the harem ladies. So, he did not have to ask for her permission. He made a snap judgement then, and ‘accepted’ the offer.

Fazl says Bihari Mal proposed and “Inasmuch as graciousness is natural to His Majesty the Shahenshah, his petition was accepted. . .” (Petition!!)

Maryam marries Akbar at Sambhar Lake:

The imperial party went on to Ajmer to the Shaikh’s tomb, there, finally, the harem ladies joined the emperor. On their return, they stopped at Sambhar Lake, forty miles west of Jaipur.

Today, the lake’s a large salt-pan, with barely any water and a surface riddled with white from the salt. It’s possible, that four centuries ago, there was water, and greenery around it, or Akbar would not have halted there.

Raja Bihari Mal brought Maryam and ‘placed her among the ladies of the harem.’

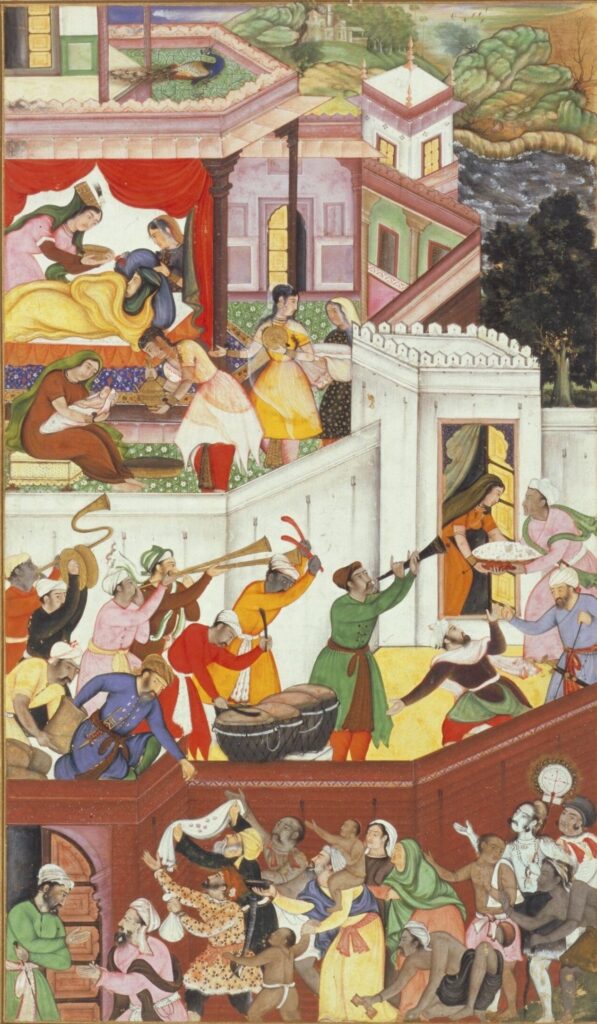

On the left is the preparation for a wedding from the Hamzanama, a Persian manuscript that Emperor Akbar commissioned and had illustrated. The bride is separated from the groom; at the ceremony, she will be veiled and not in any close proximity to her future husband.

On the right is a Hindu wedding ceremony—the bride and the groom are tethered to each other as they take steps around the sacred fire. In later years, courtiers suspected that Emperor Akbar participated in havans—fire rituals—with his Hindu wives. First Image Source. Second Image Source.

Fazl does not tell us anything about the ceremony—whether it was only a Muslim nikah, or there were some Hindu elements to it. But, there was a wedding feast, and the imperial cavalcade stopped for one day at Sambhar to celebrate.

Then, Akbar went on, and Raja Bihari Mal, his son, Bhagwan Das, and his grandson, Man Singh, went with him to find their place at the court at Delhi.

By the end of his life, Raja Bihari Mal had the highest rank at court that the nobility could achieve–a mansab of five thousand.

The future of this unnamed princess of Amber:

Fazl doesn’t say, and no other historians have named this daughter of Raja Bihari Mal—which is why several people have identified her as Jodha. I’m going to deal with Jodha in Part 3 of this blog post.

Akbar’s fourth wife is only known by the title he gave her when she gave birth to his heir, Prince Salim/Emperor Jahangir. She is called Maryam Muzzamani, and her tomb, which we’re going to visit at Sikandara, is also identified by that title.

In 1564, Maryam gave birth to two sons, twin boys called Hasan and Husain, who did not survive beyond a month after their birth.

In 1568 or 1569, Akbar and Maryam set off from Agra, on foot, on another pilgrimage to the Shaikh’s tomb at Ajmer—a whopping 230 miles—this time to pray for a son. Emperor Akbar was twenty-eight years old, he’d been married several times, and had no sons, no heirs.

On the way there, very close to Agra, in fact, they stopped at the tiny village of Sikri to visit another Sufi saint, who was a descendant of the Ajmer saint, and was called Shaikh Salim Chisti.

This Chisti promised Akbar not one, but three sons.

Maryam was either pregnant or became pregnant very soon after, and Akbar sent her to Shaikh Salim Chisti’s house in the village of Sikri to have her child.

From the 17th Century Akbarnama of Abul Fazl, Prince Salim’s birth at the Shaikh’s house at Sikri—the birthing chamber, the baby being bathed right after birth, the rejoicing in the outer courtyard, and the alms distributed among the poor. Image Sources

The details of this miniature painting (about 12” by 7”) are spectacular—they tell a whole story. There’s Maryam in an upper chamber, resting after the birth. Below, one of the women cradles the baby, while another pours water from a jug for a bath, and a servant behind proffers towels.

It’s possible that the court painter intended to denote Prince Salim’s wet nurse as the one with the baby on her lap. She was the daughter of Shaikh Salim Chisti, the Sufi saint to whose house Maryam went for her confinement. When Salim became Emperor Jahangir, he did not forget his wet nurse, or her son, Qutbuddin Khan Koka, who was—by virtue of their both having nursed at the same breast—his foster brother.

Years later, Koka, sent to arrest Sher Afghan in Bengal, would die in the conflict. Sher Afghan’s wife was a lady called Mehrunnisa—she would marry Emperor Jahangir as his twentieth wife, become Empress Nur Jahan, and the most powerful woman in the Mughal dynasty. (Oh, and Mehrunnisa is the main protagonist in my The Twentieth Wife and The Feast of Roses.)

In the other close-up of this painting, are the celebrations at the birth of a son and heir for Emperor Akbar with trumpets, drums and a cymbal. On the right, at the open door to the harem apartments, a server brings in nourishment for the lady who has just given birth.

On the left, a man throws coins to the gathered crowd below with his left hand, dipping into a sack for more with his right.

The boy was born on August 31st, 1569, and Akbar named him after the Sufi saint, Shaikh Salim Chisti, as Prince Salim.

But, Akbar never called him that, he always addressed this cherished boy as ‘Shaiku Baba,’ again after Shaikh Salim Chisti.

Maryam after her husband, Emperor Akbar’s death:

Maryam Muzzamani survived her husband for eighteen years, and died in 1623. Her son was emperor—she lived well-respected, enormously rich, owned jagirs and estates all over the empire, possessed ships that sailed the Arabian Sea routes, and traded in spices and indigo.

And all happened because her father, Raja Bihari Mal, was prudent enough to realize that Akbar’s empire was unstoppable, and that it would be wise to treat the Mughals as allies and not antagonists. And, he took that unusual step of making a first marriage of a Hindu woman into the Islamic Mughal imperial family.

We’ve now disposed off four wives; what about that most-loved one, Jodha Bai?

And, we’ll visit Maryam’s tomb.

If you’ve enjoyed reading this post, please share it, so others may read also. Thank you!

Keyword phrases: Is Jodha Akbar story real; Jodha Akbar real story; Mughal Emperor Akbar; Emperor Akbar’s tomb; Akbar the Great; Mughal harem; Mughal Empire in India; where was the Mughal Empire; Akbar’s wife.

Primary Sources: Henry Beveridge, trans., The Akbarnama of Abul Fazl, 2 volumes; Heinrich Blochmann, trans., The Ain-i-Akbari by Abul Fazl Allami; Lieutenant-Colonel James Tod, Annals and Antiquities of Rajasthan, 3 volumes; Vincent Arthur Smith, Akbar the Great Mogul, 1542-1605; Pringle Kennedy, A History of the Great Moghuls; Henry Beveridge, trans., and Beni Prasad, The Maathir-ul-umra; George Ranking, trans., Munktakhab-t-Tawarikh by Al-Badaoni; Rima Hooja, A History of Rajasthan; B. DE, trans., The Tabaqat-i-Akbari of Khwaja Nizamuddin Ahmad; William Henry Sleeman, Rambles and Recollections of an Indian Official; Beveridge, Henry, article in Journal of the Asiatic Society of Bengal, Volume LVI; Annette Susannah Beveridge, The Baburnama in English.

On the next blog post—Will the real Jodha Bai please stand up?—Two of Emperor Akbar’s wives: The mysterious Maryam and the elusive Jodha—Part 3

2 Replies to “Maryam’s tomb. Two of Emperor Akbar’s wives: The mysterious Maryam and the elusive Jodha–Part 2”