Almost from the moment that some Confederate states alienated themselves from the United States (after Lincoln was elected and before he was sworn in), it became clear that the American Civil War was imminent.

Also clear was the main directive for the Union Army—capture Richmond, the Confederate capital.

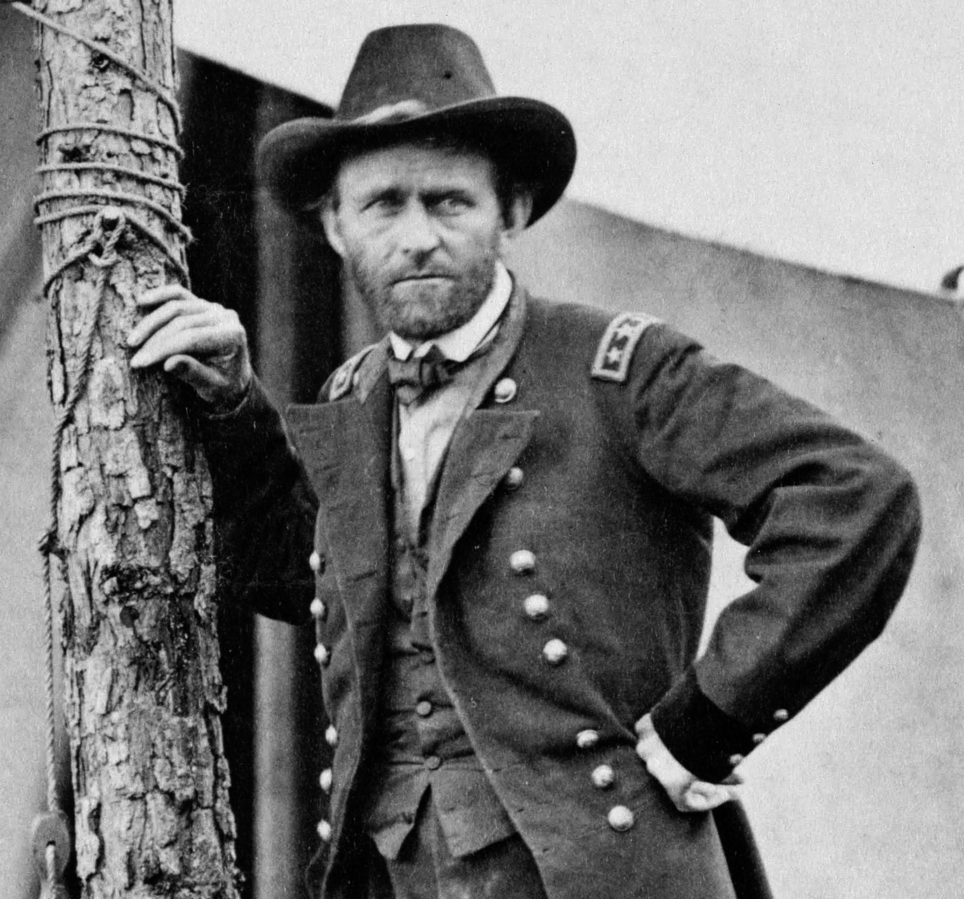

It was four years before that happened—four years, far too many lives lost, battles fought, and four chief commanding generals appointed in the Union Army. The man who ended the American Civil War, Ulysses S. Grant, was the last, and he accepted his commission from President Lincoln in April of 1864.

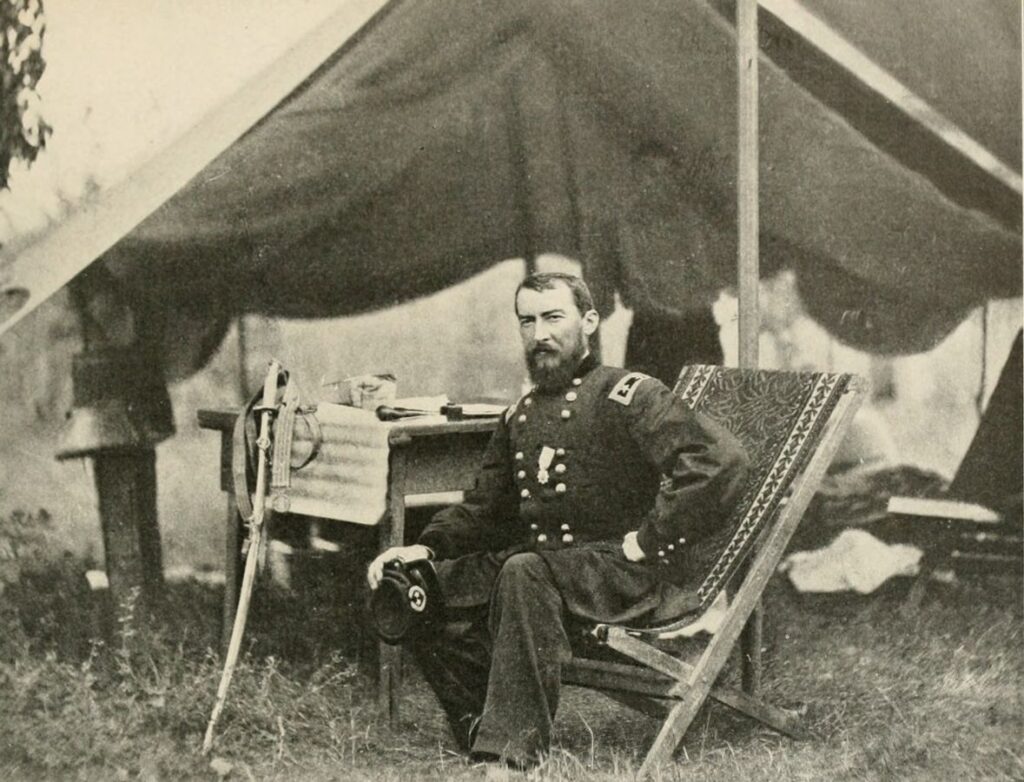

Ulysses S. Grant at Cold Harbor, ten months before he forced Lee to surrender at Appomattox Court House. Image Source.

If you recall (from Grant’s mini-biography in Part 2 of this blog post) he had been out of the army for seven years, clerking in his father’s leather store when the American Civil War began in 1861. He joined as a volunteer when President Lincoln sent out a call, and in three short years, the once-indifferent soldier became a dazzling, brilliant commander of all the Union armies.

Oh, finally, an end to the American Civil War? Richmond in sight:

By April, 1865, Grant was laying siege on Richmond—also on Petersburg, just south—cutting off supplies, trying to capture the two railroads that brought provisions, men, and artillery to the Confederates. Robert E. Lee, newly appointed to the post of General-in-Chief of the Confederate armies, was defending the two cities.

Finally, the Union Army captured Five Forks, just southwest of Petersburg, which was the main supply route to and from the Southside Railroad. (The other railroad was the Richmond-Danville line—we’ll hear more of the routes of these two railroads as we go further in this narrative.)

Petersburg now stands on shaky ground:

There were still battles to be fought the day after the capture of Five Forks, and on April 2nd, the Union army began battering away at outer Confederate defenses at Petersburg.

Grant was right there, behind his advance forces, riding around the front. At one point, he sat on a rise behind a farmhouse as he wrote dispatches to his officers.

The Confederates turned their attention to this slope and began bombing. In that cacophony and chaos of war, how could they have known that the Union commanding officer was there? It was simple, both armies had spies embedded within their ranks. And Grant obviously knew that he was providing a sitting target—a very rich prize indeed.

With shells exploding all around, his staff urged Grant to move, but he sat on, quietly at work.

By noon, all the outer lines of the Confederate defense had been decimated, only the inner lines remained. For all practical purposes, Petersburg had fallen to the Union Army.

Grant then sent his troops to capture two forts, Gregg and Whitworth. Then, he halted the fighting; one, he wanted to give the civilians a chance to escape, and two, he wanted to save his reserves to follow the rest of the Confederate army west because they would also surely evacuate.

Allow me to tender you, and all with you, the nation’s grateful thanks for the additional and magnificent success. At your kind suggestion, I think I will meet you to-morrow.

President Lincoln to General Grant, April 2nd 1865

With this confidence, at 4:40pm that afternoon of April 2nd, 1861, he sent a message to his president, saying he had captured Petersburg. Would his commander-in-chief care to visit him there on the next day?

Where’s Lee? Evacuating Richmond about now:

Richmond is only some twenty miles north of Petersburg. On this same day, the second of April, 1865, well before Grant had started his assault on the outer lines defending the latter city—around 10am or so, I think—Lee had sent a telegram to his president, Jefferson Davis, saying that it would be impossible to hold onto the Confederate capital any longer. Richmond had to be abandoned.

This note was brought to Davis as he was attending the service at St. Paul’s in Richmond.

They had known Grant was close, Petersburg would be besieged, yet, Davis had gone to church with the controlled air of one who was determined to assume normalcy. To give courage to his people that all was. . .all right.

But, after reading the note, the Confederate president left his seat and fled down the aisle even as the clergyman was in the midst of his sermon. At this, the congregation became restless, spoke in muted whispers, and the society ladies in the front pews rose and stalked out majestically. And, for those who remained, the clergyman sent around the collection box, as if to say that Confederate money would still hold weight as legal tender.

St. Paul’s Church in Richmond, as it was on April 2nd, 1865, with its 225 foot spire. The spire no longer exists. Image Source.

Official word was not sent out through Richmond until 4 o’clock, but there was no ignoring the signs of distress—similar to Davis’s accelerating lope out of church.

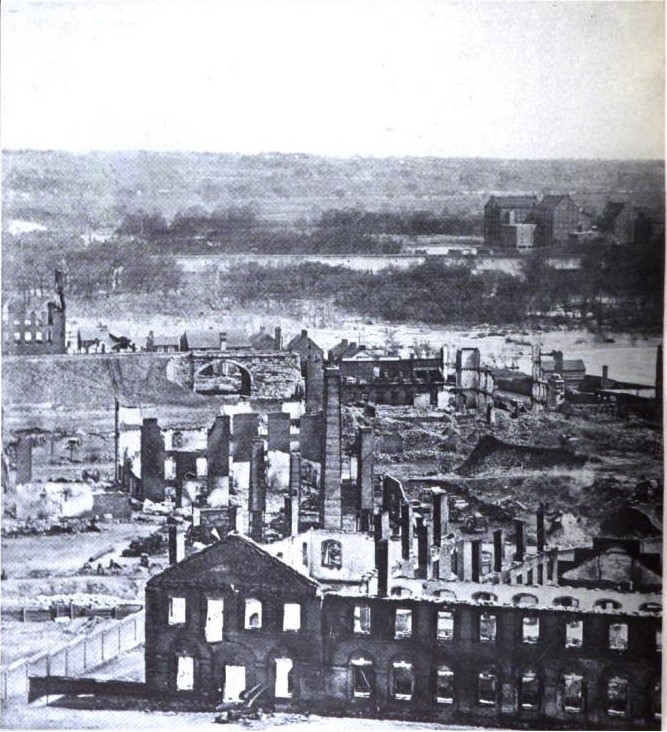

Richmond burns:

Every government office around the Capitol began destroying its papers, starting a bonfire in the square outside. The people in the actual know—government officials and leading citizens—bolted out of the city in carts, on horseback, in carriages, or any vehicle that would move on wheels. Station platforms had barely space for a footprint, the trains were packed to bursting, the waterways of the James River were clotted with skiffs, barges, boats and even crude punts—all that could float.

Trains occupied by the Confederate War Department, the treasury, the Post Office Department, and other government agencies also chugged out of the station, bloated with officials and papers.

The last few people leaving, who were to turn out the lights, did so in a spectacular manner. They set fire to the tobacco warehouses in Richmond, and parts of the city still burned when the Union soldiers entered the next day.

Richmond in, April, 1865, after the fires had been put out. Image Source: The Photographic History of the Civil War, Francis Trevelyan Miller, Editor-in-Chief, 1911.

A special train had been commissioned for Davis and his cabinet, scheduled to depart at 8:30pm, but he extended the wait, clutching at the fervent hope that Lee would send him word that the evacuation was no longer necessary. After waiting until 11 o’clock, Davis left on the Richmond-Danville Railroad, to reach Danville, from where he hoped to go further south and eventually set up his capital deeper in Confederate territory, at Charleston, South Carolina.

Grant, that same night, April 2nd, knew little of this exodus—he was waiting to enter Petersburg the next morning, but Richmond also had been abandoned.

The last time Abe and Ulysses met during the Civil War:

The Union general was up early on the morning of the third of April, waiting to hear that Peterburg had fallen. It had, and at nine o’clock, Grant rode into the town and settled into the front porch of a house belonging to a Mr. Thomas Wallace, who was very much on the Confederate side; well, being well within Confederate territory, there was a reason Mr. Wallace stayed on, his politics matched the place!

The Wallace House still stands, and probably looks the same as it did on that momentous April 3rd, brickwork, Doric columns, and that tiny front porch. Today, the land around–which had then contained stables and outbuildings–is much curtailed, and the curved balcony sit-out, left of the door, is new. Image Source: Google Street View.

But, I suppose, to the victor go the spoils, and Mr. Wallace courteously offered his house, his porch, his library, his kitchen and his cook, and anything else he could to the conquering commander of the Union forces.

President Lincoln arrived by train from City Point, which was the eastern-most end of the Southside Railroad (now all obviously under Union control). Grant dispatched a cavalry regiment to meet him, and also sent his own mount for the president to ride from the station to the Wallace House.

Grant had three horses for his use during the American Civil War—Egypt, Cincinnati and Jeff Davis. This is Cincinnati, the horse President Lincoln rode on April 3rd, 1865. Image Source.

They met in the front yard, Grant, unusually subdued (he wanted to be away, chasing after the Confederate armies), and Lincoln, exuberant, exhilarated that this long war had finally ended.

Grant comes down the steps from the front porch to welcome his president. The young boy is Tad Lincoln, the youngest Lincoln son, who would have been twelve at this time. The oldest Lincoln son (twenty-two then) was an officer in Grant’s army, and had gone to escort his father from the train station for this meeting at the Wallace House. Image Source.

Lincoln very much wanted to go to Richmond, but alas, it had not fallen yet. Or so they both thought then. Actually, Grant could very well have accompanied his president to Richmond—it had been under the control of his army from 8:15am.

Grant did not get this message until was well on his way westward, and he was most likely thankful for that. He had a great respect, and liking, for his commander-in-chief, and although the American Civil War was over, Lee and the Confederate armies were still loose, still to be captured. This was not the time for the Union commander to be dawdling over a burning Richmond.

Grant had accomplished the necessary diplomacies at Petersburg, handing the city over officially to his president; now, he wanted to be soldiering.

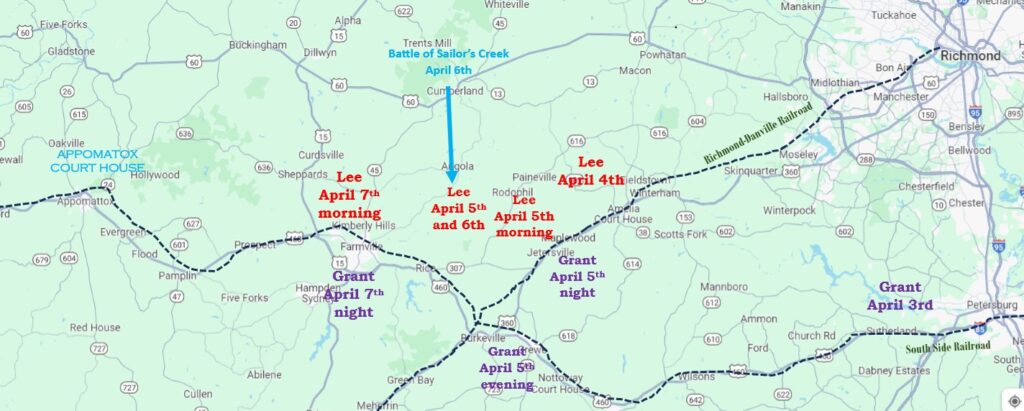

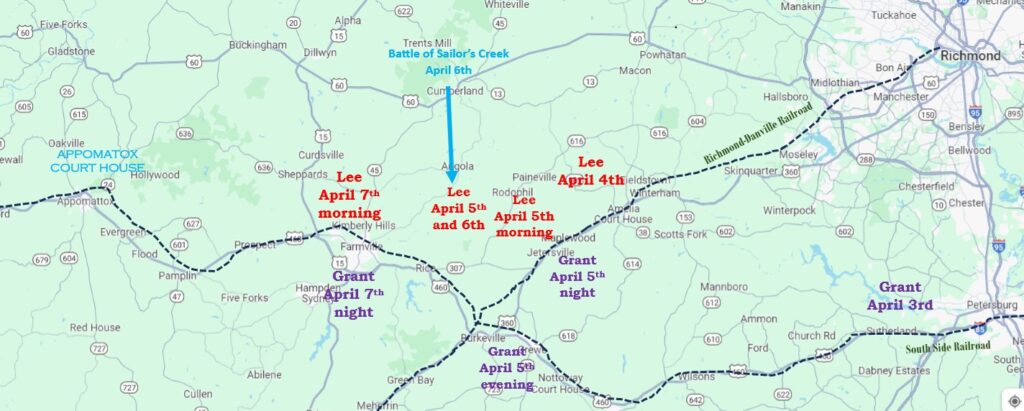

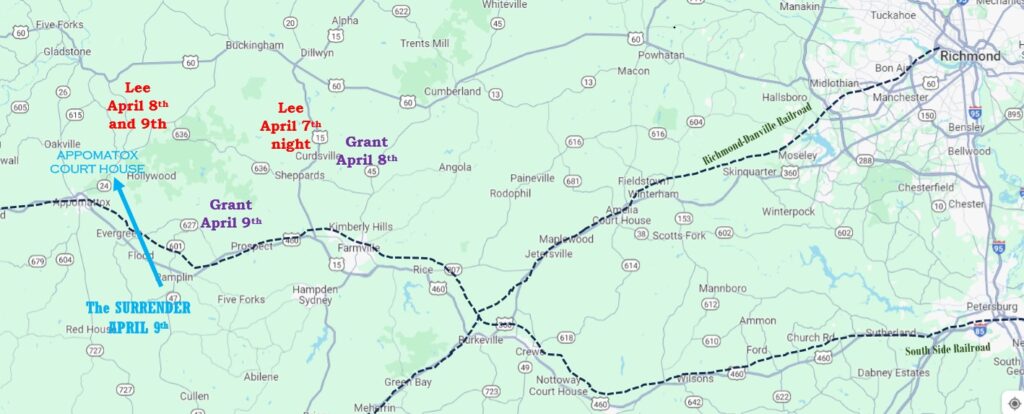

A map of Grant’s and Lee’s movements during those last seven days of the American Civil War. Here, so you can see where Grant stopped for the night on April 3rd, after meeting President Lincoln. Image Source: Google Maps. I’ve put in the legends.

At dusk on April 3rd, when he heard that Richmond had fallen, he was spending the night at Sutherland’s station.

Can a country have two presidents? It did, during the American Civil War. Where was the other one?

The next day, Grant was still along the Southside Railroad, on a wagon trail south of the actual railroad lines, when he heard news from a captured engineer at Burkeville that Davis and his cabinet had passed through that station on the morning of April 3rd, on their way to Danville.

Burkeville was the junction point of the Richmond-Danville railroad (sort of north-south on the map above) and the Southside Railroad (east-west on the map above).

And, where’s Lee about now?

Lee was following Davis on the same Richmond-Danville line, but he had left a day later, on the 3rd, instead of the 2nd, and by then Grant had been at Petersburg with Lincoln, at Sutherland station on April 3rd night, and was headed toward Burkeville (where Lee was headed) to cut Lee off.

On April 4th, as Grant was marching toward Burkeville, Lee was still at Amelia Court House on the Richmond-Danville line (marked Lee April 4th on the map). Now, Lee could no longer hope to pass through Burkeville, so he had to go west again.

Lee’s army had stopped at the station at Amelia Court House hoping to find a supply of rations from Danville, but—some miscommunication about Lee’s whereabouts—it had gone past them, to Richmond. There was no retracing their steps to Richmond which was now under Union control, so, they had to forage and find food.

Lee was isolated further when the Union soldiers took Jetersville (look just south of Amelia Court House) on the same day (April 4th) that Lee landed there, and cut the overhead lines so his president at Danville could not raise him on the telegraph.

Why did the near-miss of the train of supplies mean so much?

The Confederate Army had long been on very short supplies, with Grant surrounding them, cutting off their deliveries, reducing their food to a very minimum. During the past two months, several men had deserted, unable to put up with the deprivation. They were exhausted, and they were rabidly hungry. A long walk to wherever their homes were, was better than staying in the army, weak, unfit to serve, waiting to be captured.

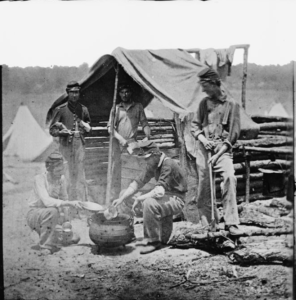

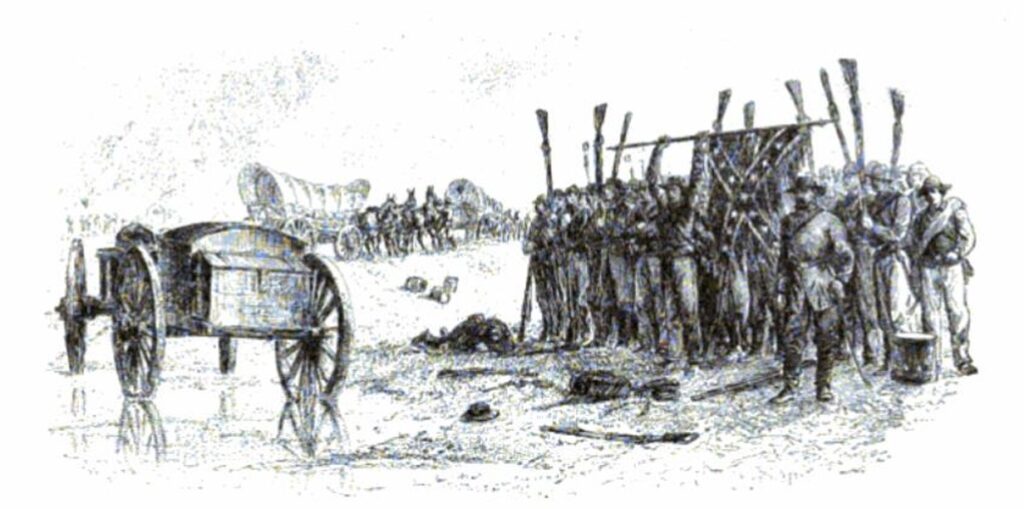

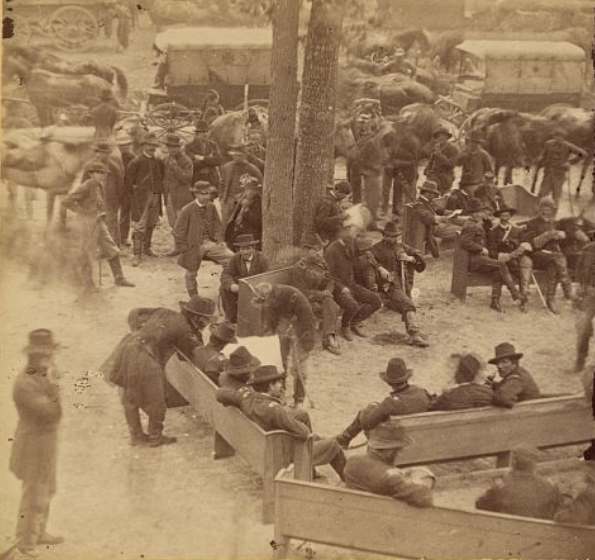

During the American Civil War, army rations at camp were a pound of dried, salted beef or pork (‘fresh’ beef in a can was a luxury), a pound of hard tack, which was a dried ‘bread,’ of sorts, and some dried vegetables.

Hard tack was wheat flour, water, and salt cooked in a pan until it desiccated into a very inflexible biscuit. The only way to eat it was to dip it in hot coffee, or soup, or a stew.

The soldiers on both sides—when things ran to plenty—were doled out dried beans, peas, tobacco, coffee and peanuts. They typically put their resources together and had a cookout. However, things didn’t run to plenty very often, especially when the troops were on the march.

Volunteers in the Union Army cooking their rations together. Image Source.

By the end of the American Civil War, the Union army managed fairly well to continue to feed and nourish their men, but the Confederate soldiers flailed.

Their wheat became corn—corn, water, salt hard tacks. Their vegetables became non-existent, excepting for peanuts. Their coffee was variously made from corn, apples or acorns, and they found a brew of chicory root the best substitute.

Lee goes further westward, and Grant pursues him:

By the time Lee neared Jetersville (still following the direction of the Richmond-Danville railroad), he realized that there was no going further along that route—the Union Army had taken Burkeville Junction. So, he started to move westward and landed up somewhere north of the village of Rice, around the Sailor’s Creek area.

A look at the map again. Lee was at Jetersville or near it on the morning of April 5th—by nightfall he had gone west to the area around Sailor’s Creek. That same night, Grant was camped where Lee was in the morning—you’ll see why as you read on. Image Source: Google Maps–I’ve put in the date legends.

A Union scout came riding up as Grant arrived near Burkeville on the evening of April 5th. The man was dressed in a Confederate uniform—so the messengers were often clad, so that they could slip through enemy lines without being killed—and tonight, because of his Confederate uniform, he was almost captured by his own Union soldiers.

This scouting, on both sides, must have been a perilous occupation—if the man managed to convince the enemy that he was one of them (he was wearing their uniform, after all), he was in danger of being killed when he entered his own lines, where some soldier with a trigger-happy finger would shoot first and then ask who he was later.

In true spy fashion, this scout pulled out a note from his mouth, where it had been lodged wrapped in foil secure within a wad of tobacco!

I wish your whereabouts, were hereabouts, instead of thereabouts:

The message came from General Sheridan, who was at Jetersville, very excited at having thwarted Lee. He updated Grant and then added a small, wistful line, something like, wish you were here. . .

Grant and Sheridan didn’t go back a long way; they only met in the American Civil War, but Grant had been impressed enough to appoint him leader of the cavalry regiments when he himself was made Commander-in-Chief a year ago, in 1864.

Grant was not very tall—five feet, seven inches in some tellings; five feet, eight inches in more generous ones.

Sheridan was five feet, five inches. There is an anecdote about his reception in Washington when he came to accept the cavalry command in March, 1864. The War Department was surprised by his size—and he had lost weight recently, topping the scales at a hundred and fifteen pounds, and well, he was short. He was to lead the cavalry?

You will find him [Sheridan] big enough for the purpose before we get through with him.

Ulysses S. Grant in Washington, crushing objections to Sheridan’s leadership of the U.S. cavalry.

Although they had ridden for a long while already this evening of April 5th, Grant decided to go twenty miles north to Jetersville and spend the night at Sheridan’s camp. It was a risky move, foolhardy even to put himself in danger—just like sitting on the slope outside Petersburg in full view of the Confederate armies.

They left with a small escort, fourteen cavalry and a few of Grant’s staff, and rode through deep woods, lit only by a waxing gibbous moon in unclouded skies—illumination enough to ride by, because they did not dare light a lantern and advertise their presence.

Their path took them very near Confederate lines; they saw fence rails thrown down on various fields to accommodate the enemy’s cavalry regiments, and the Union cavalry, they knew, had not passed through here. Soon enough, Confederate campfires glimmered through the woods. They went carefully past the Confederate armies—unlike the scout, they did not have the security of being clad in (fake) Confederate uniforms.

General Phillip Sheridan in camp. Image Source.

When they got to Sheridan’s camp, it was past ten o’clock. There was no way for Sheridan to have known if his boss was going to come in response to his summons, so he was pleasantly surprised. He welcomed them and put out a wartime feast—cold chicken, beef, hot coffee. And then, by the dying embers of a campfire, Grant and he settled down for a talk.

Lee had been very close to Jetersville that morning, and now, was not very far away, some eight miles west perhaps—although neither Grant nor Lee knew it that night. (Look at where they each were on April 5th night on the map).

One more decisive battle, April 6th at Sailor’s Creek:

A war is fought, or measured anyhow, by battles, movement of troops, loss of life, victories and defeats. But, in writing this blog post, I turned to what interested me—where Grant and Lee were during the last seven days of the American Civil War, who they met, what they said, and what they thought. But this battle was important, so we will visit it very briefly.

On the 6th, Grant went back south to Burkeville Junction (where he had been the previous evening), and Sheridan pushed west with his cavalry near Sailor’s Creek, following Lee’s footsteps.

Here, the Union Army and the Confederate Army fought the last decisive battle of the Civil War. At the end of it, the U.S. Army had captured seven thousand Confederate soldiers, and more importantly, six of their generals. One of the generals was Custis Lee—Lee’s oldest son, the one who had followed him to West Point and graduated top of his class (Part 3 of this blog post).

General Ewell and his troops surrendering at the Battle of Sailor’s Creek, on April 6th, 1865. Image Source: Battles and Leaders of the Civil War, Volume 4. The Century Company, New York. 1888.

(Just a reminder about Ewell (see Part 2 of this blog post). He was Grant’s commanding lieutenant at his first posting after West Point. When Grant was transferred out, he asked Ewell for a few days leave to go courting his wife, to ask her to marry him. Ewell agreed. And now, this April 6th, 1865, twenty years after, Grant had captured Ewell. See what I’ve been saying about connections between people during the American Civil War?)

Abandoning Richmond had been that closing of the coffin, this Battle of Sailor’s Creek with the mammoth arrest of soldiers and several generals, was that proverbial final nail in it. Everyone knew it, Lee did also.

Perhaps only Jefferson Davis, in Danville by now, fiercely pawed at a glimmer of light. But the Confederate president was not there by Lee’s side, not on the ground, and knew nothing of daily movements of his army because the Union army had cut off their communications by slicing through the telegraph wires.

However, that day, a messenger had found his way to Lee from Davis, riding hard for two days. There were words of encouragement and a thinly-veiled order: Stand your ground, do not surrender at any cost.

If Lee had not seen the writing on the wall, Wise read it out for him:

As Lee was mulling over this directive, on the evening of April 6th, one of his generals, Henry Alexander Wise, came with contrary and forceful counsel.

The men were exhausted, under-fed, sleep-deprived, with no will to fight. No matter where they turned, they were pursued by the Union army. It would all end in more bloodshed. Capitulation was the only solution. The men needed to go back to their homes and pick up their lives as best they could.

And there, by Lee’s campsite, Wise bellowed out his advice, painting an idealistic portrait of surrender, freedom, and a slip back into normal life—as though the last four years of the war had not devastated almost everyone, in comrades lost, animals slaughtered, farms left without able-bodied men to work on them, women scrabbling a desperate existence from idle fields.

Concede, Wise said, and all will be fine.

It was April, just the time for ploughing. Concede, and the men would go back to their homes and their fields, turn the soil, sow and weed, and harvest blissfully later this summer. If Lee continued in this futile war which needed to end, and more men died, their blood would stain his hands forever.

Lee was thoughtful for a long while.

What of their country, he asked.

They have no country, Wise replied, their loyalty is to you. If you ask them to carry on, they will, but they have not the heart for it anymore.

Looking back, as we do now at the Civil War, how long it lasted, how utter the devastation was, it’s a testament to both Lee’s and Grant’s leadership that they were able to demand and acquire the devotion of their men, soldiers and generals alike.

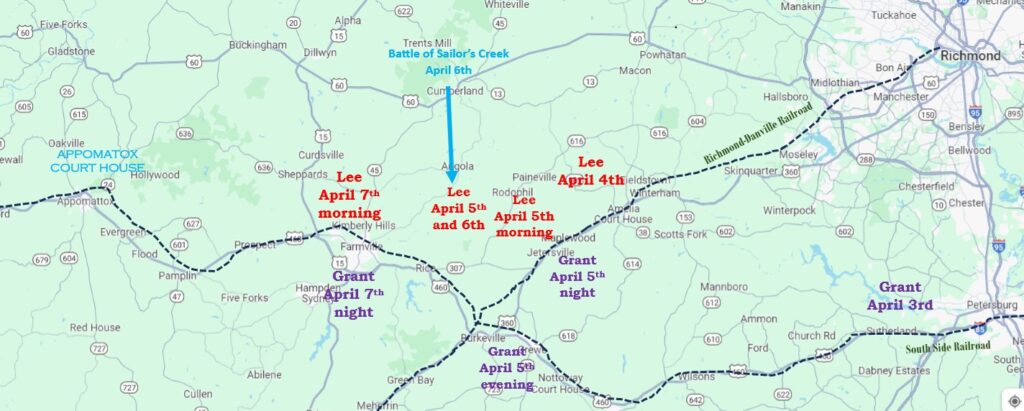

Lee’s at Farmville on the morning of April 7th—and then north at Sheppards and Curdsville. Grant arrives at Farmville on the night of April 7th. Image Source: Google Maps–I’ve put in the legends.

The next morning, April 7th, Lee went to Farmville (on the Southside Railroad, just west of Burkeville) just before the Union Army got there, and managed to find rations for his men. But the respite was brief, and he turned northward into the country.

He had already sent a message to Jefferson Davis—his first direct communication since they all fled from Richmond—that he would have to surrender.

Even so, Lee moved on.

Glory, Glory, Hallelujah!

Grant was again right at Lee’s heels on April 7th—by noon, he arrived at Farmville and settled into the one hotel in the town. Logically, the next place Lee would go to refuel with provisions was almost certainly Appomattox Station (marked as Appomattox in the map; just west of Appomattox Court House). Sheridan was already on his way there, to cut off Lee’s retreat.

And so, we’re now approaching the place of the surrender.

Appomattox Station in 1865. Lee’s supplies arrived on the morning of April 8th and they were being loaded onto wagons and carts when the Union Army ambushed them. Image Source : The Photographic History of the Civil War, Francis Trevelyan Miller, Editor-in-Chief, 1911.

At 5p.m., on April 7th, 1865, Grant wrote the first of his letters to Lee, essentially saying (like the Borg!) that resistance was futile.

Then, Grant ordered a regiment that had accompanied him to Farmville to march on to support another. The men were shattered, they’d already walked far today, but they lifted their weary limbs and set off on their general-in-chief’s command—again, that devotion I just spoke of.

And now, Grant experienced one of those moments of grace that touch us all at times in our lives.

Night had fallen, and it was dark and indistinct outside the porch of the hotel where Grant had established his temporary headquarters. The soldiers lit little fires along the road in front, grabbed straw and made torches that they held aloft as they marched by. And began singing.

Grant rose to his feet and he and his staff stood against the railings, watching the men. One young voice began ‘John Brown’s body,’ that had become the battle hymn of the Union forces, and when the chorus came. . .

Glory, Glory, Hallelujah

Glory, Glory, Hallelujah

Glory, Glory, Hallelujah, But his soul goes marching on. . .

The chorus of John Brown’s Body by Stephen Vincent Benét

. . .everyone joined in. Maybe, Grant did too, under his breath, as he listened to these young men who had given so much already, their voices sweet and hoarse, going to another battle from which some of them would never return.

Perhaps Grant thought of his father at that moment. Jesse Grant had been employed by Owen Brown, John Brown’s father, and it was from him that Jesse had learned to be a staunch abolitionist, and it was Jesse who had taught his sons that same maxim that all men were indeed created equal.

Grant had been slow in coming into the fold, not because he believed in slavery, but because he had not believed in the secession that would follow an attempt to abolish slavery—the splitting apart of his country into two, the chance of an American Civil War—and he had thought that they went together.

But once President Lincoln had won the election of 1860, once the first shot had been fired at Fort Sumter, Grant had joined the volunteer army on the side of the Union.

And now, he was standing here, commanding these men, at the very brink of the end of the American Civil War—an end he had brought about.

That night, at midnight, Grant received Lee’s answer: what were to be the terms of the surrender?

Grant’s and Lee’s movements on the last two days before the surrender at Appomattox Court House. Grant follows Lee up north from Farmville as they exchange letters, to keep close to him. On the 8th, he is where Lee was on the 7th. Image Source: Google Maps–I’ve put in the legends.

The day before the surrender:

When he woke that morning at the hotel in Farmville, Grant briefly wrote out his terms of surrender and then went up north toward Curdsville, where Lee had been the previous night, and where one of Grant’s generals was following Lee closely to cut off his rear flank.

Grant took up quarters in a white farmhouse that night, April 8th, waiting for Lee’s response. He was sick, plagued with headaches, drained by the chase, wearied by the long war. He was so close to the end; when would it be over?

His men gave him a mustard foot-bath and tried all they could to make him comfortable. He slept in the front parlor of the farmhouse, and his staff was in the opposite room, across the corridor.

Ummm. . . I did not mean to surrender:

Lee’s reply was unsatisfactory at the very least. He had never intended to surrender his Army of Northern Virginia, he only wanted to know what the terms of surrender would be. Would Grant be willing to meet him on the old Richmond-Lynchburg stagecoach road (Lee was in the hills north of Appomattox Court House, very close to that stage line) so that they could hash out terms of peace?

Grant read the letter and crawled into bed again, sickened by this response.

The next morning, he declined the peace talks. He would not bandy words anymore, he had laid out his terms for Lee’s capitulation.

He had no authority to proclaim peace, he said, only to accept the surrender of Lee’s army. As a soldier he could do no more.

The first photograph was taken in May, 1864, about a year before the surrender at Appomattox Court House. It was outside Massaponax Church in Virginia—one of Grant’s councils of war. The soldiers had brought the church pews out under the trees. Grant is on the left, standing, leaning over a pew and his generals, pointing at the map.

The second photo is a view of Massaponax Church with the Union Army soldiers around. First Image Source. Second Image Source.

Then, the Union Army general went down south again along his original route, not choosing to follow Lee to the north of Appomattox Court House.

Close to noon on April 9th, 1865, Lee sent up a white flag in another letter that found Grant some six miles east of Appomattox Court House. He’d gone to meet Grant for the peace talks, but Grant hadn’t been there. He was now willing to surrender on the terms Grant had previously offered.

Grant agreed; he would meet Lee wherever he wanted.

That wherever became the village of Appomattox Court House. An hour later, about 1pm, Grant rode into the village and headed toward the Mclean House where Lee was already waiting for him.

How did the Mclean House, the site of the surrender, make it into history?

Lee’s headquarters were northeast of Appomattox Court House, and he went toward the village, stopped just north of the Appomattox River in an apple orchard, and sat waiting for Grant’s reply.

It came after noon, in the hands of a Union soldier, Colonel Babcock, who rode up to Lee along with Lee’s military secretary, Colonel Marshall. Then, they set off to the village to find a place that would be worthy of this meeting.

It cannot have been an easy day for Lee, nor could the surrender have been an easy decision. He had not yet heard from his president Davis, his own first communication to Davis (since the flight from Richmond) had just reached Danville the previous day. In that, Lee had said that surrender was inevitable.

Davis’s return message exhorting him to continue the fight was still on its way. It would not reach Lee in time, because by then, he had signed the surrender documents.

However difficult and painful, Lee had made the decision to capitulate—it was the right decision, and any further delay would have only resulted in a further loss of lives, unnecessary, avoidable, and uncalled for. The defeat of the Confederate armies had been assured as soon as Petersburg and Richmond had fallen.

Lee and his generals. Image Source.

And then, Lee had come to surrender personally. He need not have, but he did. As much as Grant was exhausted by this time, Lee was also. Fatigued from the long American Civil War, sick to heart at having seen his soldiers desert over and over again, knowing he could not feed them, and indeed, not having eaten much himself, because there were simply no rations either for the men or the officers.

Lee and Babcock reined in just outside the village, and Marshall rode on to find a house or a structure that would shelter them.

They could have met outside, it was fine day. It had been a mild spring that year, 1865.

The rain and mud had made the armies miserable, but in the countryside, trees were setting leaf; on the Appomattox River, the willows had begun to bud even as they trailed over the waters, birds chirped in the warm air, and wild turkeys gobbled in the distance.

Wilmer McLean steps into history:

The first man Marshall saw was Wilmer McLean. Was there any place they could meet?

Now, McLean had originally lived near the Bull Run River in Viriginia, very close to Manassas—and depending on who you talk to, the first battles of the American Civil War, the first real engagements, that is, are either called the First and Second Battles of Bull Run or the battles of Manassas. (Hence, the American Civil War is bookended by the phrase ‘From Manassas to Appomattox’).

McLean’s home was so close to the Manassas conflict that some of the fighting went on in his fields. The Confederate general Beauregard appropriated his mansion there, called ‘Yorkshire,’ and then turned it into a hospital and occupied it. One of the first shells from the Union Army exploded through a log cabin outbuilding that was used as the kitchen and scatted dirt and logs over the food. (See Part 1 of this post).

Wilmer McLean around 1860—this is pretty much how he must have looked that morning of April 9th, 1865. Image Source.

After the Second Battle of Bull Run (a year later), McLean left his home and moved two hundred miles away, to Appomattox Court House in 1863, trying to flee from this American Civil War.

And here was a Confederate colonel in uniform, asking him for a space where. . .well, it’s not quite clear how much information Marshall had given McLean at this point, only that he wanted a space.

But first. . .McLean’s (somewhat) connections with both Grant and Lee:

As I’ve been researching these blog posts, it’s been curious how people have been so connected with each other, by place, family and chance. America was a very small country then, it would seem, and everyone either knew everyone else, or lived in the same place, or married into a distant branch of the family, or. . .something.

As he stood there, that morning of April 9th, Wilmer McLean had no idea of his later fame. Perhaps he was just exasperated that the war had followed him thus far, into the village where he had moved to avoid it.

But, he also didn’t know then that Grant and he, and Lee and he, could trace some link in the past.

During the war, the Grants had moved to Burlington, New Jersey; rather, they moved their children there, and Mrs. Grant was often somewhere by the side of her husband or waiting close by during the American Civil War.

Wilmer McLean’s maternal grandfather had lived a few houses away. Sort of a connection between McLean’s past and Grant’s present.

But it’s also possible that McLean’s older brother, Samuel, lived in Galena, Illinois—where Grant was working in his father’s leather business before the American Civil War.

Galena was a small town, and the McLeans would have been some sort of prominent citizens (the Grants certainly were), so Grant may well have recognized the name when he came to the village of Appomattox Court House.

And the McLean-Lee connection?

Wilmer McLean grew up in Alexandria, Virginia. He most probably attended the free Alexandria Academy, beginning about 1821 (when he was seven). At the same time, there was a fourteen-year-old boy at the Academy in a higher class—Lee. They would have overlapped for three years, although, given their age difference, it’s unlikely they knew each other.

But. . .maybe. Maybe. As I said, small country then.

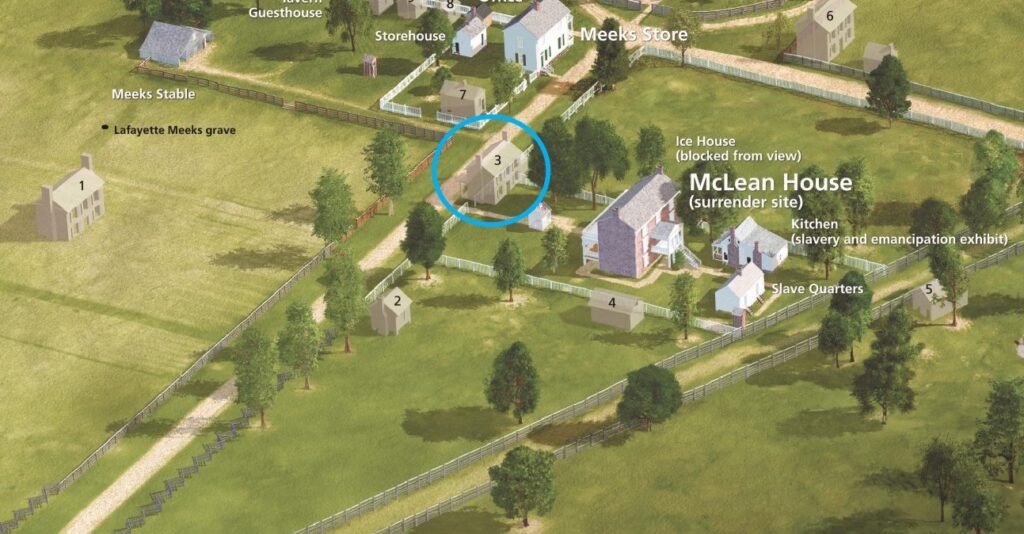

How does this unused building at Appomattox Court House look?

In all the narratives, it’s only said that McLean showed Marshall a building which the latter did not like at all, and then, either McLean offered his own home, or Marshall saw it and appropriated it.

I’ve been curious about the first place McLean showed Marshall and have been studying the map of the village intently, trying to figure out which it could have been. Marshall, in a later account, only says that it was ‘dilapidated and. . .had no furniture in it.’

It’s possible of course that McLean pointed to a barn or a shed, possible, but the ‘no furniture’ part makes it seem as though it was a formerly inhabited structure. (In any case, Marshall understood this meeting to be momentous—it couldn’t have been a barn or a shed. Were the two generals who ended the American Civil War expected to sit on hay bales during the signing?)

McLean also could not very well have taken Marshall to a house that had belonged to someone else, even if unoccupied then. So, it must have been something that belonged to him.

The old Raine Tavern marked in the blue circle, in the front yard of McLean’s house (which was the new Raine Tavern). It’s a ghostly figure in this NPS map, because it doesn’t exist anymore. But, in 1865, it was there, not used, an empty building. Not inhabited, but certainly had had furniture in it before! And, more importantly, it belonged to McLean. Image Source.

My guess is that McLean took Marshall to the (old) Raine Tavern. The Raines had owned the Clover Hill Tavern in the village (still exists), then they sold it and built a tavern here, south of the stagecoach road in 1846. It was a substantial two-storey building, but less than two years later, Raine built a larger tavern (the new Raine Tavern) just behind, which, in time, in 1863 in fact, became Wilmer McLean’s residence. (See Part 1 for a more extended Raine history.)

Both the old and the new Raine Taverns belonged to Wilmer McLean.

In this view, looking east, you see the court house directly ahead. The road is on the same path as the Richmond—Lynchburg stagecoach route. It came into the village directly behind the court house, curved north and south around the building and then came straight ahead (toward us). On the right is the McLean house as it stands today; the little white lattice-work structure, in the front yard, surrounds the well. Directly in front of the well, abutting the road, would have been the (old) Raine Tavern that Marshall would have seen and dismissed as not adequate. Image Source: Appomattox Court House, NPS brochure (2002?)

So, it’s likely McLean first showed Marshall the disused old Raine Tavern. And likely that Marshall sneered at the decaying building, looked beyond and saw that handsome red brick house with its wide front porch and its general air of habitation and comfort—McLean’s residence, the ‘new’ Raine Tavern.

Just as Mr. Wallace had had no option but to offer his hospitality to Grant in Petersburg, just seven days ago, Wilmer McLean could not say nay to a Confederate colonel, to whatever room he wanted to occupy in his house.

Marshall checked out McLean’s front parlor and went back to his general and the Union colonel Babcock to tell them he had found a place.

General Lee went in, sat down in a chair to await Grant, and during that time, drained and fatigued, he fell asleep.

Grant comes by:

A half-hour later, Grant rode into the village. Babcock had left his orderly outside to direct his general to the McLean house and the man flagged them down and showed them the way.

Grant and his staff had met generals Sheridan and Ord, and other officers, waiting at the edge of the village and now, they all assembled in the front yard of McLean’s house.

Grant went in alone, up the stairs to the front porch and through the front door. Colonel Babcock, who had been watching for their arrival, opened the door to the front parlor.

Lee rose from his cane-backed chair and the two generals shook hands.

Lee was clad in a new dress uniform of Confederate gray, with a sash, and a sword with gold-work on the scabbard. His boots were new, embroidered with red silk at the shins. Everything about him was trim.

Not so Grant, who had ridden in from the field. He was wearing a ‘blouse’ coat of Union blue flannel, open at his throat, his shirt showing, a sugar-loaf hat, his trousers tucked into his boots, and mud splattered on both. Grant was dressed like a private in the Union Army. Only, on his epaulets, he had the three gold stars that denoted his rank.

They were vastly different men otherwise also. Grant was fifteen years junior to Lee, had no gray in his brown hair and beard, stooped a little. Lee towered over him by five inches, stood erect, his white beard and full head of white hair combed neatly.

Colonel Babcock now went out to invite the rest of the Union officers in, on Grant’s request, and they filed in quietly and arranged themselves around the room. There’s no actual account of who exactly was there, how many, but the Union officers far outnumbered the two representing the Confederate side—Lee and his military secretary, Colonel Marshall.

Perhaps this was a calculated move on Lee’s part; he had come to surrender and could not have come with a show of force.

Grant and Lee meeting at McLean’s front parlor on April 9th 1865. The people identified in this portrait are: Lee, seated on the left, and Marshall leaning against the mantle. Porter (aide-de-camp to Grant) is standing on the left. General Sheridan is near the fireplace (and next to Marshall); Babcock (with sword) is in the front in that line. Image Source: Campaigning with Grant by General Horace Porter.

Grant now began speaking of having seen Lee during the Mexican War, some twenty years ago. He had been a lieutenant during that war, Lee had been part of the commanding general’s staff, several ranks higher. Grant remembered Lee, the latter did not, but said he was trying to recollect.

It was Lee who brought up the reason why they were there—Grant had been enormously courteous, reluctant to rush matters and injure Lee’s dignity; he was here as a victor and wanted to extend every civility to his opponent.

What were the terms of the surrender, Lee asked? The same as he had offered in his letter two days ago, said Grant.

Would he write them out again, so that there would be a record and no possibility of misunderstanding?

Colonel Parker, a Native American on Grant’s staff, brought him a little wooden table from the edge of the room, and Grant wrote out his terms in pencil.

The Confederate Army was to surrender, the officers would be paroled individually and could not again take up arms against the United States. All the artillery and property of the Confederate Army was to be given up, but the officers could retain their personal sidearms, their horses, and their baggage.

Grant, photographed with his staff earlier in the Civil War. Colonel Ely Parker is third from left. Image Source.

Lee hesitated for a while after reading these terms. It was all very well, very generous indeed, to allow the officers their personal property, but. . .perhaps General Grant did not realize that the cavalry and the artillery also had brought their own horses and mules to the Confederate Army.

Would it be possible to allow. . .well, Lee did not actually ask that favor, but Grant gave it anyhow, saying he would not change the terms as written, but when his officers paroled the men, they would be allowed to choose their own mounts and take them back home.

The reunification begins. . .with the terms of the surrender in Confederate ink and Union paper:

When it came time to commit the surrender document to ink, McLean’s parlor had none. The only person with an ink box in his pocket was Colonel Marshall, and Colonel Parker copied out Grant’s letter using his ink.

When Lee had to write out his letter of acceptance, they had no paper, and the Union generals provided it.

As that was being done, Lee remarked that he had no provisions for his men—for the last few days they had been living upon parched corn. Sheridan had captured the Confederate provisions at Appomattox Station, and Grant promised Lee 25,000 rations for his men.

When the terms of surrender had been signed, and the letters exchanged, Lee and Grant shook hands again. It was now about 4 o’clock—they had been together some two and a half hours.

Lee leaves the McLean house after the surrender meeting, as Grant bids him farewell. Image Source. Appomattox Court House, NPS Brochure (2002?). Painting by Keith Rocco.

Lee and Marshall went out first, and the general’s horse, Traveler, was brought to him. As he mounted, Grant came out and lifted his hat in farewell. The Union officers also saluted Lee in the same way, a salute he returned.

And then, he turned his horse around and rode away northeast back to his headquarters.

The day after the surrender:

Grant and Lee met again the next morning for a conversation about peace, about what was to happen now, if Jefferson Davis, the Confederate president would also surrender.

They were both aware that in the end, they were simply soldiers who had negotiated a. . .sort of truce, but an important one. Would the other Confederate armies surrender so easily? Wasn’t Lee’s influence great, could he not effect that?

The second (and last) time Grant and Lee met was on a small rise of land, east outside the village of Appomattox Court House, in the open. Image Source.

After that meeting, Grant went back to the village and sat on McLean’s porch in the sunshine.

Later that day. . .

The American Civil War had made rivals of men who had grown up together, stood up at each other’s weddings, married each other’s relatives, had learned their soldiering skills at West Point, and had finally to confront each other as enemies.

Confront, and in some cases, kill.

After Grant’s second (and forever last) meeting with Lee outside the village, a few of the Union officers crossed over Confederate lines to meet their erstwhile friends. Two Confederate generals, Wilcox and Longstreet, came back with them to meet Grant.

Longstreet had been at Grant’s wedding to Julia Dent; he had known Julia’s brother also—they had all been fellow cadets at West Point. It must have been an emotional meeting for Grant and Longstreet, a rekindling, finally, of a long and varied friendship. Even though they now met on unequal terms, victor and vanquished.

By noon, Grant was on his way to Burkeville Junction to catch a train on the Southside Railroad all the way to City Point, where his wife waited aboard a steamboat for him. He spent two days with her and then they went on to Washington, arriving on the morning of the April 13th.

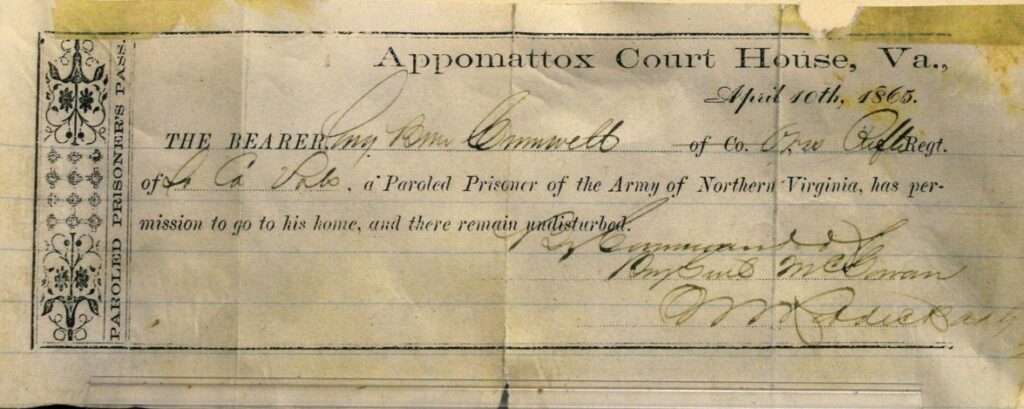

Lee stayed on for two more days, overseeing the laying down of the arms and the beginning of his army’s parole, the forms for which were printed in the Clover Hill Tavern in the village. And then, he too left the Appomattox area on the 13th of April.

One of the parole passes for Lee’s surrendering Army of Northern Virginia, which were printed in the Clover Hill Tavern at Appomattox Court House. Some 28,000 such passes were printed. Image Source.

Grant met his grateful president on the 13th and the morning and afternoon of the 14th. Lincoln had arranged for them to go see a play that night at Ford’s Theatre. Would Grant and his wife come?

Thank you but no, Grant said respectfully, they wanted to leave by the 4pm train to get to Burlington, New Jersey—they had not seen their children in a long while.

So President and Mrs. Lincoln went without the Grants to Ford’s that evening, the 14th of April, 1865. By eleven o’clock that night, John Wilkes Booth had fired the shot that injured Lincoln mortally.

By the next morning, the president who had brought about the emancipation of 4 million slaves and had reunited the country, was dead.

If you’ve enjoyed reading this post, please share it, so others may read also. Thank you!

Keyword Phrases: Surrender at Appomattox Courthouse; Battle of Appomattox date; Appomattox Court House date; Appomattox Battle Significance; who surrendered at Appomattox Court House; Who won Appomattox; Where is Appomattox.

Primary Sources: Campaigning with Grant by General Horace Porter, 1897; Lee at Appomattox by Charles Frances Adams, 1902; Various NPS brochures; The End of an Era by John S. Wise, 1901; Personal Memoirs of U. S. Grant, 1894; The Life of General Robert E. Lee by G. Mercer Adam, 1905; A Personal History of Ulysses S. Grant by Albert D. Richardson, 1885; Ulysses S. Grant by Owen Lister, 1901; Memoirs of Robert E. Lee by A. L. Long, 1885; Life and Letters of Robert Edward Lee by Rev. J. William Jones, 1906; Biography of Wilmer McLean by Frank P. Cauble, 1969.

On the next blog post—we visit the village—as it was then, and as it is now—The End of the American Civil War—Appomattox Court House—At the village—Part 5

3 Replies to “The end of the American Civil War–Appomattox Court House–The Last Seven Days–Part 4”