Kumbakonam is a city in southern India where God dwells. In plenty. There are some 200 temples, most dedicated to Shiva, some to Vishnu and one of the very few places of worship to Brahma.

That is not all. Drive outside the city limits, and you will invariably glimpse the gopurams—the entrance stupas—of hundreds more etched against the sky. That is because the city is itself of great antiquity, inhabited since pre-Vedic times in ancient India, although most of the existing temples are either of more recent construct or date back to the 7th Century or so.

The Airavateshwar temple. Source

In the suburb of Darasuram is the Airavateshwar Temple (phonetically, eye-ra-va-teysh-var), built in the 12th Century by Rajaraja Chola II. The Chola dynasty of ancient India has given us another two magnificent temples in Tanjore and Gangai-konda-cholavaram (mouthful, I know, but if you speak Tamil, it’s self-descriptive) and all lie within fifty kilometers of each other in the state of Tamilnadu.

These were the Later Cholas, ruling from about 850 CE to 1279 CE. The dynasty itself has a farther-reaching history—very well established, and known by their literature, from the 1st to the 4rd Centuries CE, and somewhat murkily in the background as far back as 300 BCE.

But first…

Let’s step back, way back, into ancient India:

The Aryans migrated to India from about 2000 to 1500 BCE, possibly drawn by the opportunities offered in the highly sophisticated cities in the valley of the Indus River. (Mohenjodaro and Harappa, two of those cities of ancient India, date approximately to the time of both the Pyramids at Giza and Stonehenge—my blog posts about the latter, Part 1 here, and Part 2 here).

And then, the Aryans stayed on in large numbers, merging into the population, bringing their language, assimilating it with the local tongue, and, the Vedic Age began in India.

First, Prakrit, and then Sanskrit developed as the language of the masses, and the Vedas and the Puranas (ancient texts of wisdom and deportment) were written. Hinduism, a co-mingling of pre-Aryan religion and the new, post-Aryan era, took shape as we recognize it. The Mahabharata and the Ramayana were composed around 400 BCE (more or less).

Look at a topographical map of India, and you’ll see, midway, a series of mountains, the Vindhyas. For the longest time, it does not seem as if this new society ventured south beyond this range.

The histories of ancient India—the ones that exist today—mention very little detail of southern India, other than that some migration south took place. But who ruled? How long? What did they build? How did they live? Who were their friends, and who, their enemies?

One of Emperor Asoka’s rock edicts. They’ve been found all over northern India. Source.

We know so little—I mentioned earlier the murky lurking of any sort of historical narrative—but there is something to tell us about the south Indian kingdoms.

Emperor Asoka (c. 300 BCE) obligingly left us stories cut into rock, massive boulders and polished pillars. In the thirteenth of his rock edits—which primarily details his conquests of Greek kings, he mentions the names of four kingdoms, and here, finally, comes the first notice of the Chola kings.

Great territorial conqueror as Asoka was, these Tamil kingdoms of ancient India lay outside his empire, but he traded with them, offered them knowledge of medicinal plants, and sent his Buddhist missionaries to preach dhamma, the core principles of Buddhism.

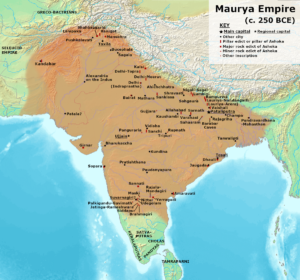

Asoka’s Indian empire encompassed modern-day Afghanistan, Pakistan and Bangladesh, but look at the south, all clear and green, not under the purview of this great emperor. Source.

And, the (sudden and strong) light at the end of the tunnel: After this relative blank in the history of the south in ancient India, there’s a veritable hoard of information from the 1st to the 4th centuries CE (called the Sangam Age) that finds us bang in the middle of three prosperous reigns, the Cholas, the Pandyas and the Cheras.

The literature takes shape in the form of ten anthologies of more than two thousand poems. They are written in Tamil (my mother tongue)–the oldest language that has endured from ancient India–but Sangam Tamil poems already show incursions of Prakrit and Sanskrit into the idiom, another proof of a long-established interaction with the north and the Vedic people.

Although the Tamil texts of these two great Hindu epics haven’t survived, both the Mahabharata and the Ramayana were already translated into Tamil by now. And, interestingly, all three southern monarchies claimed some sort of descent from feudal lords of both the warring factions in the (northern) stories of the Mahabharata.

The three dynasties of the Sangam Age, circa first to the fourth centuries. The Early Cholas are on the east coast, note their capital city of Kaveripattinam. Source

And, just who were these Early Cholas?

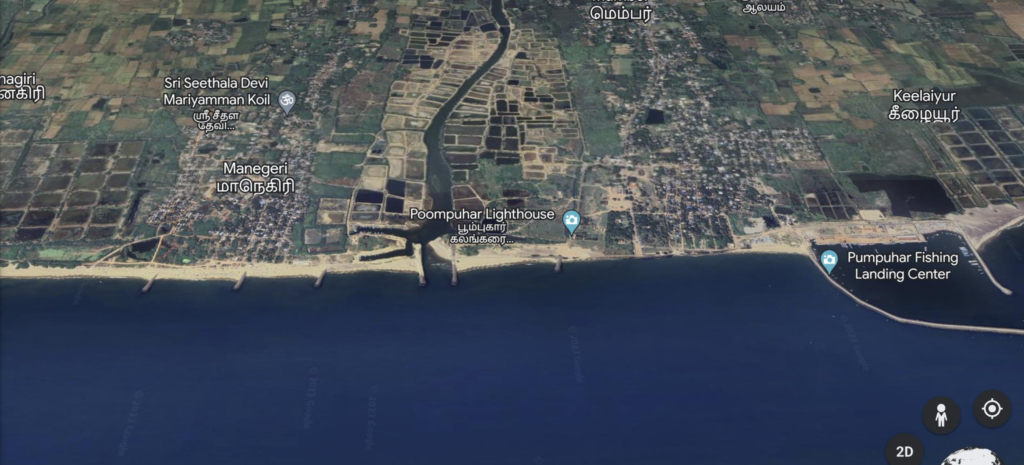

The most prominent king of this, early, Sangam Age of the Chola dynasty was Karikala (c. 190 CE). There are accounts of his battles with the Chera and Pandya kings, of his defeats and his victories, and of his capital city, ancient Kaveri-pattinam, on the mouth of the Kaveri River. (Not to be confused with modern-day Kaveripattinam in the state of Tamilnadu, this city was at modern-day Poompuhar, also in Tamilnadu).

The city of Kaveripattinam (I am—and will be—referring to the ancient city from now) flourished on the northern bank of the river, which was then wider than it is today, affording deep water moorage well inland.

It had two distinct parts—one at the place where the Kaveri drained into the Bay of Bengal, and the other, further up-river. The port part was naturally smelly with the fish-catches, noisy with the lading and unlading of goods from the massive ships that came to trade, thronging with crude, unwashed sailors from other parts of India and from other countries, and crowded with foreigners.

Roman coins have been found in various places in Tamilnadu, and Pliny, no less, bemoans a deficit in trade with Indian ports.

The mouth of the Kaveri River at present-day Poompuhar, where the ancient city of Kaveripattinam was situated. Source: Google Earth

Further up-country, away from all this mess that brought them splendid riches, was the genteel part of Kaveripattinam. Here, the river ran smoothly by, and cool breezes floated over well-planned and well laid out streets, with names like Royal Street, Car Street and Bazaar Street.

In between these two distinct parts of the city was a nice, disinfectant span of empty space, lush and tree-lined, studded with more shade trees in the grounds that hosted a weekly bazaar and meetings, so that you did not come directly from the stink of the docks into the elegant neighborhoods.

King Karikala had his palace, I’d imagine, on the riverbank, with the best views of the Kaveri’s clear and placid flow, and the sheen of an amber-hued sunset upon its waters. Surrounding the royal palace were the houses of the royal charioteers, mahouts, cavalry and the personal bodyguard. The servants, entertainers—court jesters, musicians, dancers—flower-garland makers, pearl-threaders, night watchmen and timekeepers who cried out the passing of the hours, all lived a little farther away.

Tradesmen and craftsmen also lived in this part of town, and in what we now know to be a feature of ancient Indian society, each street accommodated a particular trade—the Brahmin priests, the merchants, the astrologers and the doctors.

Away from the precincts of a city like Kaveripattinam, entire villages would host inhabitants of one caste or trade.

The Sangam Age manuscripts were written on palm-leaf ‘paper,’ similar to the ones in this photo, collated with a string through the holes to hold several leaves together. This particular one does have a part of a Sangam Tamil poem on it—but it’s a (later) copy—to preserve the manuscripts, they were copied out when the palm leaf deteriorated, and thus, some of them have been preserved. The original, from the 3rd Century or so, could not have survived. Source

We visited the Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library at Yale University this summer and they house their books in this light-temperature-and-humidity controlled gigantic glass cube, several stories high. It’s an absolute marvel, and I can’t help thinking that some of these very rare Indian manuscripts ought to have an abode such as this!

Mansion of the Gods:

King Karikala had a dazzling palace in Kaveripattinam, lofty and spacious. Artisans came from various kingdoms—smithies in gold and silver, carpenters, masons and mechanics who put together such an astounding edifice that legend came to call it the work of Mayasura, architect to the gods.

In Hindu mythology, Mayasura built a palace for the Pandavas in the Mahabharata, and was father-in-law to the demon king, Ravana, in the Ramayana—impressive credentials indeed, and, the ability to span across both the major Hindu epics!

But read a description of the earthly Chola palace and you will see why it was worthy of such praise.

The throne room, the sabha where the king held his daily audiences, had walls clad in beaten gold. The ceiling, carved and fretted, was held up by pillars of pure coral, studded with diamonds and rubies. And the bead curtains were made of pure pearls, shining soft and lustrous.

There’s obviously no photo/drawing of the Kaveripattinam palace hall—this photo is from the Mysore Palace. Imagine the pillars to be of coral and the luster of pearls—and the grandeur must have been similar. Source

Perhaps as a testament to King Karikala’s skill at diplomacy, various kings from northern India sent not only trained craftsmen to build the palace, but also dispatched gifts of immense value to adorn it.

The throne was decorated with a canopy of pearls sent by the king of Vajra. The king of Magadha sent all the furnishings—presumably, gold and silver cloth, hangings, the throne itself, carpets, and those curtains of pure pearls. The king of Avanti stepped outside the court hall, and his workers built the lofty, decorated gateway into the palace.

Garden of the Gods:

It’s a flat land, that, surrounding the banks of the Kaveri where it empties into the Bay of Bengal.

But that did not deter the sovereign. His landscapers raised small hills to break up the uniform horizon, dug lakes to set a shimmer of light in this heated land and to invite the nesting of water fowl, and created tiny ponds within the gardens with pure crystal beds that glimmered in the brilliancy of the sun. Trees provided shade, so also did artificial grottos and caves. And much like later French gardens, there were hedges formed into mazes for the pleasure of losing yourself for a short while within a forest of green.

All this was watered and kept fresh by wells ‘worked by machinery;’ in any case, there was no need to look far for water, the Kaveri flowed close by.

As a consequence of all this luxuriance of flora, game also flourished in the park surrounding the gardens—quail, hare, deer and mountain goats.

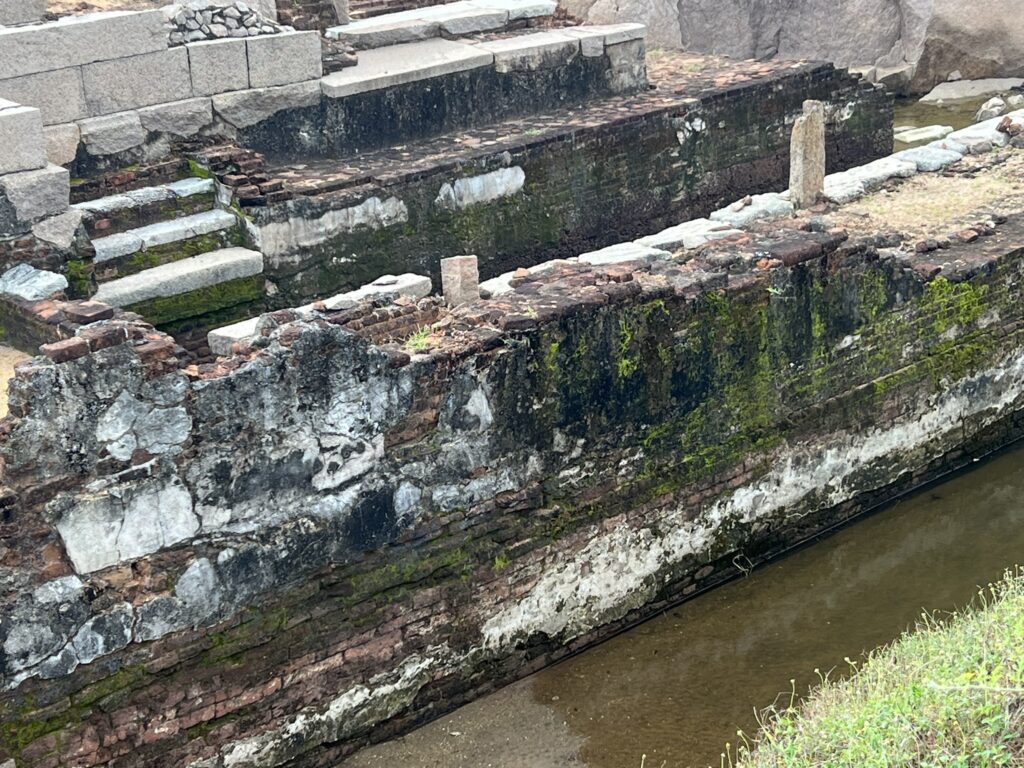

The 2004 tsunami uncovered a rock inscription that led archeologists to the site of this stone Murugan temple. Excavations revealed an 8th Century stone temple, and below, the brick-and mortar foundations of an earlier Sangam Age temple. And so, it’s known that stone architecture came a few centuries after the Sangam Age.

There were several temples—to Shiva, to Indra, the king of the Gods, to Kama, the God of Love, to the sun and the moon. And also, to Indra’s white elephant, Airavatam, who lent his name to the Airavateshwar temple in Kumbakonam that we will visit.

The Chola kings, historically, were Shaivaites, followers of Shiva. (The photo above is of a Murugan temple—Murugan is Shiva’s son). And they demonstrated their devotion in the number of Shiva temples in and around Kumbakonam. The Airavateshwar temple in the Darasuram suburb of Kumbakonam—which we will get to, I promise!—is also a Shiva temple.

We’re wandering now through the lives of the Early Cholas, and the Airavateshwar temple was built by one of the last of the Later Cholas. And, a span of five hundred years separates them, for the Later Cholas didn’t come into existence until about 850 CE. (This span is in itself quite exciting to contemplate, and we will…when we get there in this history of the Cholas).

These Early Cholas are fascinating, not just for the expansive view they give us of life in ancient India, but also because I think that it’s a complete picture, of the way distant past and, er, the somewhat not so way distant past of the Chola dynasty responsible for the temple. (From where we sit, both are way distant, of course—the Early Cholas ruled from about the first to the fourth century; the Later Cholas from the ninth to the thirteenth).

Because not much changed in their mode of life, their devotions, their conquering spirit, or their understanding of a king’s duties and his responsibilities, not just to his God, but also to his people.

The poetry of the Sangam Age, which so wonderfully details life in Kaveripattinam—ports, palace, trades and professions—interestingly omits the situation of the nobles of the court. Where did they live?

With the crush of royal employees surrounding the palace, courtiers, perhaps, lived at a distance. They had the means—a horse, a chariot, a bullock cart—to attend their sovereign at the daily audiences.

If true, it’s still a curious layout for the city. Perhaps the king thought of the convenience of those who worked for him in menial positions and could not afford a long commute to work. Or perhaps, he was only thinking of his own, in having his servants nearby?

It must have, however, been a lonely existence for the king, and I think, reflects what the poems describe as the essential character of a leader in ancient India.

If you’ve enjoyed reading this, please consider sharing by emailing a link to the post, and by hitting the social media share buttons below, so others may read also. Thank you!

Keyword Phrases: Chola dynasty; Chola dynasty architecture; Chola dynasty temples; Chola dynasty history; Chola dynasty time period;

On the next blog post—the burdens (and pleasures) of kingship in the Sangam Age–Ancient India–The Airavateshwar Temple–Legacy in Stone—Part 2

Very happy to see this article…Enjoyed reading the facts about Airavateshwar temple😍

Thank you!

Appadi podunga aruvala…this blog is such a delightful read.

Many years ago, then crazed with delving into the Mughals story, I read your 20th wife (Mehrunnisa’s romantic story beats any Mills & Boons!), Feast of Roses, Shadow Princess…supplemented with Alex Rutherford’s (pseudonym of Diane Preston) Mughal hexalogy. I was an expat in India then. I groused a bit on your Bath Abbey blogs – why the distraction into the history of our colonists, I wondered. Anyway, that was then…a peeve that doesn’t deserve a second glance.

Recently, I started poking around on S. Indian history and temples; and imagine my surprise, Gmail presented me with your blogs. Big brother is watching, grr…but this time, it did me a good turn.

Keep at it, Indu…you lace history with romance and poignancy, it’s not a dry diatribe of size, shapes, and chronology.

Looking forward to more. If your book tour brings you to Dallas, I’ll be sure to look you up.

Thank you! And also for all the history you’ve written. I’m chuckling at your Bath Abbey comment 🙂 I’m writing blog posts as I travel, you know, and it makes our travel that much more fun if I know the history behind everything–and then, I relive the trip in writing the blog posts.

Thanks again!

Independently, my Amma WAed the link to this Airavateshwar blog. Imagine her surprise when her non-religious lost-to-the-US brat of son, not only had already read it, and spoke fluently about the topic! I write blogs on my adventure travels, not nearly as enthralling as yours, but it is something. Scroll down to Narratives & Pictures for my 4-5 day backpacking in Grand Canyon with my son https://www.travelstosavour.com/grand-canyon/#1697690598078-bf1d8a9a-5a97b87d-36be

Nice 🙂 and thanks for the link. Your photos are great.

Enjoying your blogs immensely! I enjoyed your Mughal series very much! Looks like you are preparing to write a series of books on Cholas and others around the first and second chola dynasties! How very exciting and look forward to more blogs and wishing fervently you would write books about these periods. I started with Nilakanta Sastri’s old History of South India and then Kalki’s works. Not enjoying Sandilyan’s attempts afterwards that much. Just started reading some Kannadasan’s attempts. Wish more light was thrown on the History of South India with all these kings having fabulous empires, trading internationally and being world citizens that early in the history of India!

Thank you for this comment!

I’m very glad to hear you mention Nilakanta Sastri’s History of South India–it is the first book I picked up to research this blog post, and I found it enormously informative and well-written.

Visiting the Airavateshwar Temple and writing these posts has certainly sparked my interest in the Cholas. For the longest time, I’d thought that the history of southern India was not well documented, as much as, say the Mughals in my Taj Trilogy. That’s substantially true, perhaps only in that I don’t read Tamil, and so am reliant on English translations. (I don’t read Persian either–the language of most Mughal documents and histories–but the Mughal manuscripts have been, historically, translated into English by the British in India).

But, I’ve begun thinking about the Cholas after all this discovery I’ve made for these blog posts, and that thinking and reading will go on for a while–as I work on something else now.

Thanks again.

It is a pleasure going through this blog article. Lots of facts and apt comments are overwhelming. Very enriching.

Thank you; glad to hear you enjoyed reading the post.