Part 1 here

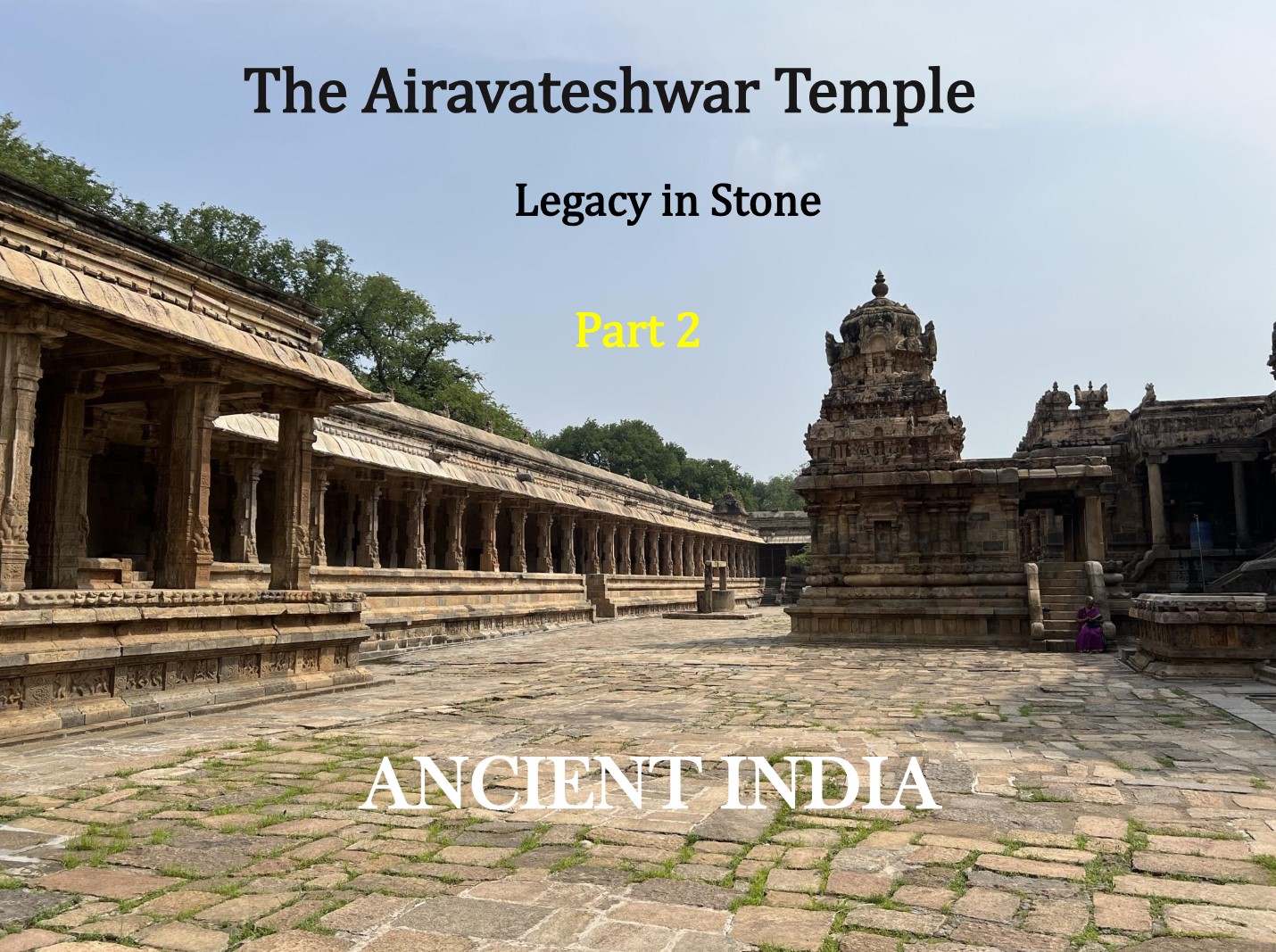

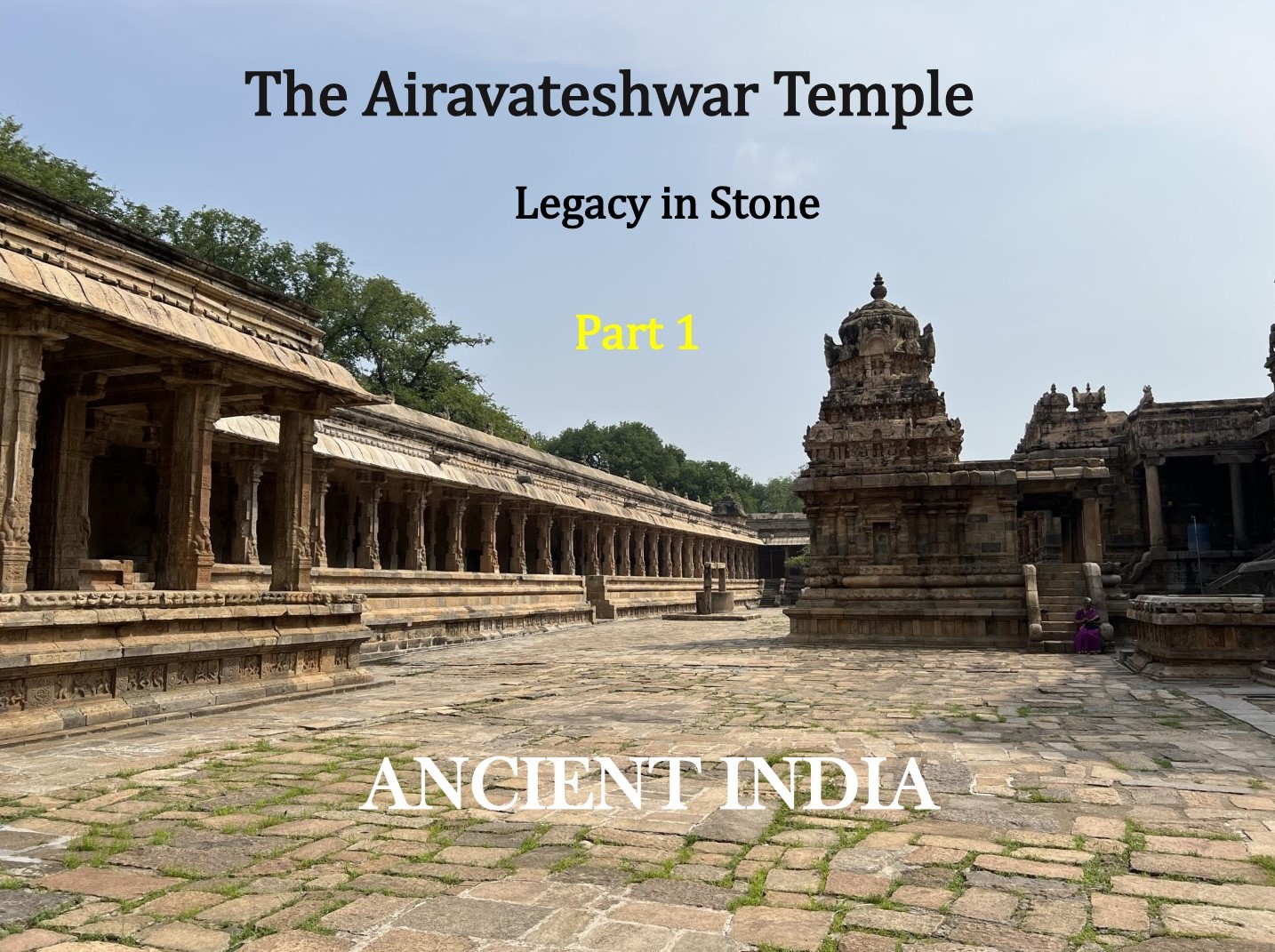

We’re on our (somewhat leisurely, I know!) way to the Airavateshwar Temple in Kumbakonam in southern India, built by the Later Cholas who ruled from the ninth to the thirteenth century. Later, because yes, there was the Early Chola dynasty in ancient India from the first to the fourth centuries, and a gap between these two during which the entire dynasty disappears from all historical story line.

In the first post, I introduced the Early Chola dynasty, because their reign—even that far back—is surprisingly well documented in more than two thousand poems written on palm-leaf manuscripts. (This is the oldest known history of south India.)

We visited the Early Chola dynasty King Karikala’s capital city at Kaveripattinam in the modern-day state of Tamilnadu, flitted through his palace, wandered down streets, stood at the docks at mouth of the Kaveri River, and marveled at the brisk trade and the mammoth ships from other parts of India and from Egypt.

Continue Reading