(Part 1 here)

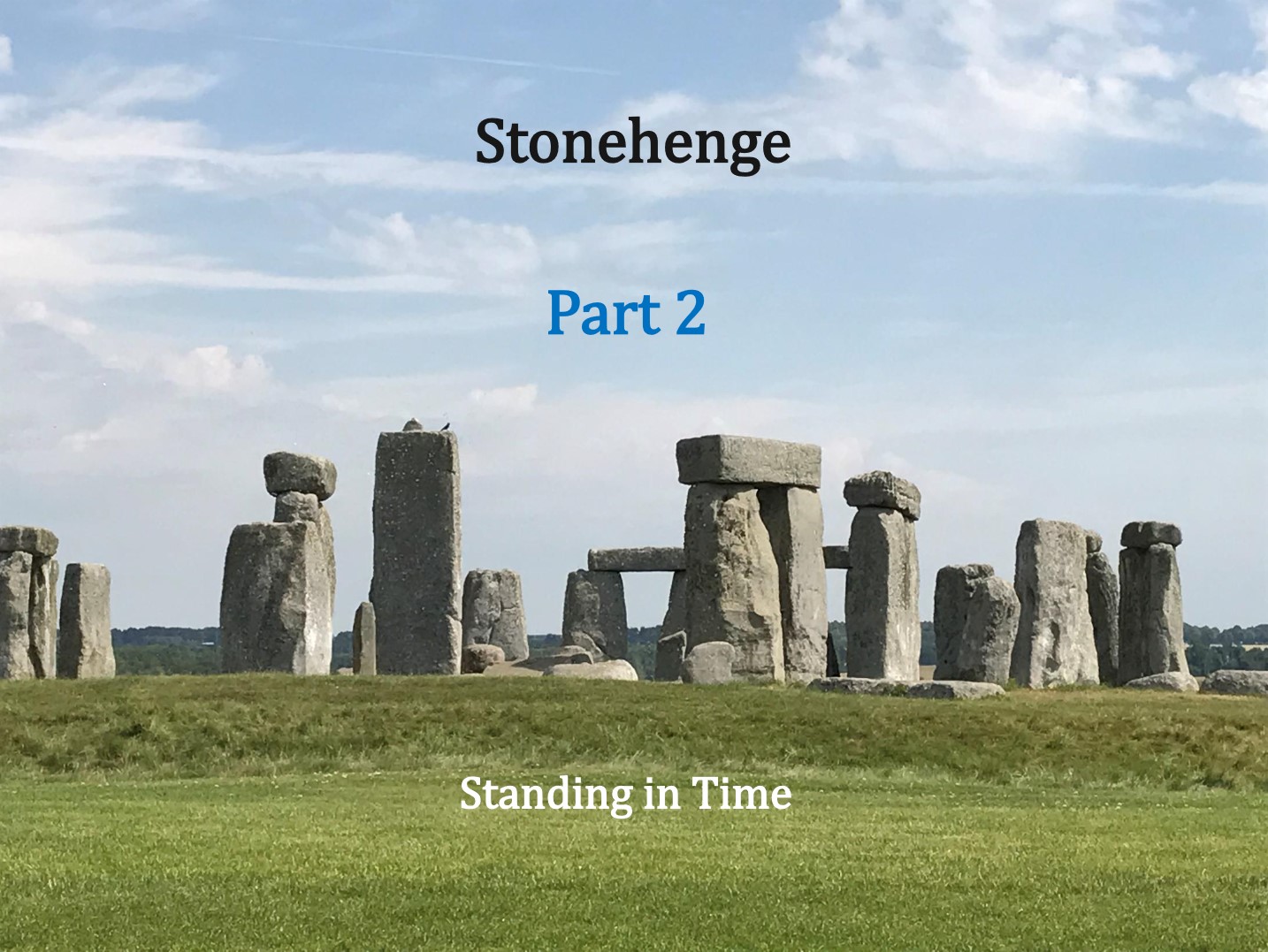

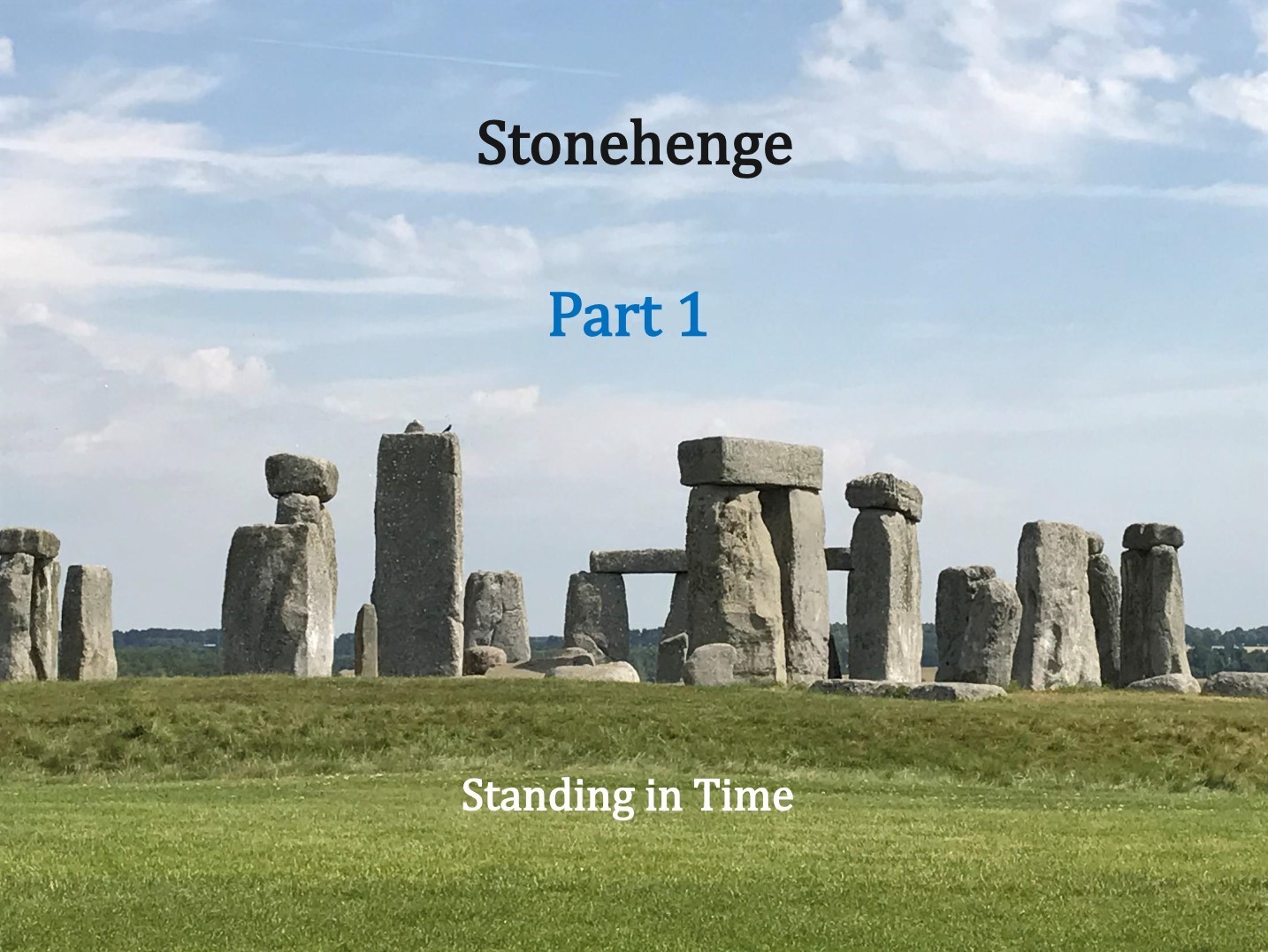

What is it? What was it used for? Circles beget circumambulation, and so several guesses have been made that it was part of the ritual at the stones. This, going around as a form of prayer, is still present in Hindu temples and ceremonies. It’s called Pradakshina (Sanskrit for ‘moving to the right’), and in temples, devotees set off on a clockwise path around the deity, or brides and grooms around the sacred fire during a wedding ceremony.

The Stonehenge stones are also arranged on a northeast/southwest axis in line with the midsummer and the midwinter sun—on the day of the summer solstice, the sun rises and strikes the northeast entrance to the stones; on the day of the winter solstice, the sun sets at the southwest point of the circle. Stonehenge has been dated (at its earliest) to the end of the Neolithic period, around 3000 BCE, and construction continued for a good 800 years after. If the stones stand today, more or less as they were composed some five thousand years ago, with that northeast-southwest axis, then the reasoning is that Neolithic man knew something about the sun, the moon and the stars. And they followed the path of the sun, and understood what the summer and winter solstices were. So, it’s an observatory of some kind? Something that allowed Neolithic man to track the movement of the sun?

Continue Reading

The front of Chawton Cottage, where Jane Austen spent the last eight years of her life. Source: Jane Austen: Her Homes & Her Friends, by Constance Hill.

The front of Chawton Cottage, where Jane Austen spent the last eight years of her life. Source: Jane Austen: Her Homes & Her Friends, by Constance Hill.