Economics at Bath:

What, you might ask, does the church of Bath Abbey have to do with the study of economics? Follow me here for a bit, please.

Take an Economics 101 class, and you will learn that Adam Smith is the ‘father’ of modern economics. If Smith’s the father, then Thomas Malthus, with his theory on food production and population growth, is surely the ‘son’ of. I’m muddling around here a bit, but what I mean to say is that both Smith and Malthus were hugely influential in their economic philosophies.

I write fiction now, but I do have three degrees in economics, and when I heard that Thomas Malthus was buried at Bath Abbey, I had to go pay my respects at his memorial.

Malthus’ theory of population explosion is simple and reasonable enough. If food production grows, then it doesn’t necessarily, over time, lead to a better standard of living, because the population growth will eventually eat up all the food surplus.

The Romans are coming!

Long before Malthus (or Adam Smith or Bath Abbey itself), in the 1st Century CE, the Romans invaded England in waves. Around 50 CE they built the beginnings of the Roman Baths in Bath, using the natural mineral hot springs. (My Roman Baths blog posts—Part 1 here, Part 2 here).

Today, the Roman Baths front a small, flagstone courtyard. The Romans also built a temple to Minerva next to their baths and kept a fire burning day and night in front of the altar, which was fed by local coal from Newton.

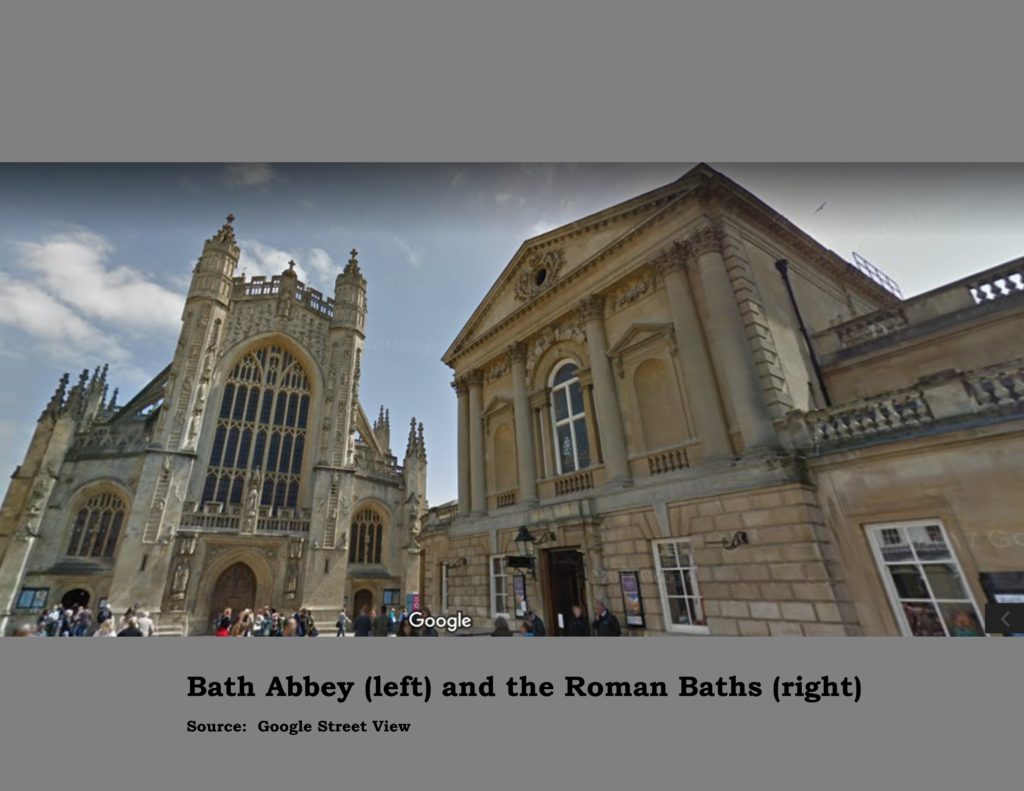

The temple doesn’t exist anymore, but right next to the Roman Baths is Bath Abbey—you literally turn left while you face the Baths and walk across a little, paved courtyard to the main entrance to the Abbey. So, it was speculated that the abbey sits on the site of the ancient temple to Minerva.

Bath Abbey straight ahead; on the right the building is the Roman Baths.

Perhaps. As with anything else that far down years, it’s difficult to substantiate this. Perhaps also, the temple to Minerva was part of the Roman Baths complex itself (i.e., it didn’t stretch east onto the site of the Abbey).

And then came the Saxons:

The Romans left Bath (and England) in the 5th Century and the Saxons were called in by British chieftains to aid them with various other invasions. The Saxons came to help and—in the manner of other ‘helpers’—took over and settled down in the country. Not without a fight though.

One of the earliest Saxon religious establishments at Bath was a nunnery, given by a grant to the first abbess, Bertana, by the King of Wessex, sometime around 675 A.D. (Good time here to visit the Max Gate blog posts if you haven’t already; Part 1 here and Part 2 here—it’s Thomas Hardy’s house and Hardy, of course, set his novels in the fictional county of Wessex, choosing the name from this very place in ancient English history).

Anyhow, back to the nunnery, which lasted about a hundred years, and then was destroyed to build instead a church for St. Peter on the site.

There’s a fair amount of doubt about when the church was built, or rather, if the current Bath Abbey is based on this church from the 8th Century, or that early original had been destroyed and a newer one built in the 9th Century on the same site. Whatever its origins, by the 10th Century—before the Norman invasion of England—there are references to a church of St. Peter in Hot Bathum.

Nave, looking east.

The Clergy fight at Bath Abbey:

Around this time, while the Saxons still ruled, there was a change in the leadership at the Bath church because of some sort of religious politics. The clergy at Bath church did not get along with the clergy at other places (most notably, it would seem, the Bishops of Worcester and Winchester) and these other bishops petitioned Rome to get rid of the Bath clergy. Archbishop Dunstan lent his weight to the argument, and a Papal See replaced the clergy at Bath with monks from elsewhere.

(I’m a little shaky about the relationship/hierarchy between the priests and the monks at Bath Abbey/Monastery, even after reading the histories, but follow along, please!)

Elphege then became the first abbot of Bath Abbey. He was an extremely devout man, spare and sparse in his needs, and when the people showered him with gifts and money, he took the bounty, built himself a palace which he then gave to the monks, and then went to live in a small house in the neighborhood.

The Saxon king Edgar was crowned in Bath Abbey on May 11th, 973 A.D. Edgar, suitably grateful to be ‘hallowed to king’ in such a magnificent church, gave the abbot grants of money and land to expand and remodel the church. After this, there is a gap in the history of the abbey until the Norman invasion of England.

And so, came William:

William the Conqueror established Norman rule in 1066 and ruled until his death in 1087. He had been the Duke of Normandy and had laid claim on the throne of England, because he was related to the previous king and considered himself heir. But William hadn’t actually lived in England until he took over rule of the country and to apprise himself of this new land, he sent out his men to do an official, and extremely exhaustive survey.

Think of it as a census, if you will, but not just of the population, but everything—the land, the churches and their wealth, the number of people, what they owned, how much it was worth in hides no less, sometimes down to the last sheep and pig.

This massive survey is called the Domesday Book. According to the Domesday Book, Bath Abbey had an annual income of something like 72 pounds. It owned property in Somersetshire and Gloucestershire, twenty-four burgesses paid twenty shillings each, a mill brought in twenty shillings in income, and there was a twelve-acre meadow.

Bath Abbey also had some very precious relics. If this list is all true, they’re priceless: the bones of St. Peter; the arm of St. Simeon; the ribs of St. Barnabas; the heads of St. Bartholomew, St. Lawrence and St. Pancras.

And, others like these: Part of Christ’s garment; part of Christ’s sepulcher; part of the pillar on which Christ was bound; the clean cloth in which Christ’s body was wrapped. The list also includes other relics of the Virgin Mary and Mary Magdalene.

It’s a truly impressive catalogue, and I’m not sure that Bath Abbey still holds all these relics, because the first mention of these relics comes from this 11th Century Domesday Book, and soon after, there was a plunder of the abbey—not sure by whom or why.

The magnificent vaulted ceiling of the nave. For a long while, the Abbey did not even have a ceiling, so this dates to about the 17th Century.

Three Bishops of Bath Abbey:

By 1090, Bishop John de Villula was ‘given’ Bath Abbey, and the entire city of Bath. These were not democratic times, clearly! Ten, years later, when Henry I became king of England, he extended the powers of the clergy and the monks at Bath, granting them more land, and allowing them to be exempt from civil lawsuits—the only thing the clerics could be tried for was robbery or murder. It must have been a good gig if you could get it.

John de Villula is said to have torn down, or demolished Bath Abbey and built a new one either on the same site or on the same foundations. When he died, he was buried in this new church.

In the early days, John de Villula had treated the monks severely, divesting them of their properties and lands, and leaving them a barely subsistence income. But he repented his harshness and in 1106 signed a deed in which he restored the lands and wealth to the monks, and also ‘my whole armoury, my clothes, my bowls, my plate, and all my household furniture, I give to St. Peter and his monks forever, to their own use and property, for the remission of my sins.’

Bishop John lived on until December, 1122, and in the meantime built a palace for himself west of the church (so, somewhere in that little stone-paved square in front) and also added two baths—a public one called the Bishop’s Bath and a private one called the Prior’s Bath.

There’s a theory that these two baths were not ‘new;’ they were built on or remodeled on existing Roman baths. There is, however, no contemporary sign of either of these baths today.

The next bishop, Godfrey, received further bounty from his king, Henry I, who gave Bath Abbey the lands and the manor house in Dogmersfield in Hampshire—it became the summer home of the clergy.

The manor house doesn’t exist anymore, in its place is a (much later constructed) mansion, which is now a hotel, and called by the same name, Dogmersfield House. (Jane Austen knew the then inhabitants of Dogmersfield Park, which is east of her market town of Basingstoke. Perhaps, a fact not of much interest to too many people—but it certainly is to me.)

Dogmersfield Park, home to the Mildmays in the late 18th Century. Jane Austen met them frequently at local balls–their son, Henry-Paulet St. John-Mildmay, caused a great scandal when he ran off with his wife’s sister. Source.

Under Bishop Robert, the next person to hold that position at the Abbey, the entire city of Bath burned down, along with the church of St. Peter. This seems like a terrific event, such widespread ravage, but there’s some doubt about whether part of the city was destroyed, or part of the church, or the whole of the church…what is documented is that Robert completed the remodeling on the church of St. Peter at Bath.

So, it’s likely that the church did not burn down, or was just partially damaged—else, building it entirely, from the ground up, during one Bishop’s tenure at the church would have been impossible, surely?

The Choir stalls.

The Bath Abbey church changes:

And so, the church at Bath continued on, with frequent squabbles arising between the monks and the clergy. The bishopric of Bath also included the church at Wells (southwest of Bath) and the appointment of the Bath bishop had to be done by the monks at Bath and the clergy at Wells. At one point, it was agreed that the bishop would now be called of ‘Bath and Wells.’

Minor disagreements aside, the entire religious establishment in England was upended when Henry VIII created his own religion, the Church of England, and broke away from the Roman Catholic Church.

Henry sent out his people to demand that the existing churches give up their Catholic faith and convert to this new religion. In that purge, the monastery at Bath bowed to the dictates of its king and gave itself up on the 27th of June, 1539.

Five years before, the value of the monastery was recorded at approximately £695.

The Pews.

That brought an effective end to the monastery at Bath, whose monks had been known for not only for their erudition but also their physical industry. Soon after the introduction of weaving in England, the monks at Bath had taken up this new pursuit to such good effect, that the city became a center for finely woven woolen cloth, and the shuttle, it is said, became part of the arms displayed on the abbey house.

King Henry VIII then gave the monastery and the lands it had owned outside the city to one of his loyal supporters, and a few years later, the monastery’s within-city-limits properties went to form an almshouse for the poor.

If you’ve enjoyed reading this, please consider sharing by emailing a link to the post, and by hitting the social media share buttons below, so others may read also. Thank you!

Keyword Phrases: When was Bath Abbey built; Bath Abbey Cathedral; Bath Abbey Ceiling; Bath Abbey England; Bath Abbey England; Bath Abbey history; Bath Abbey UK

On the next blog post—Bath Abbey–A Storied History–Part 2—Prior Birde’s Chantry Chapel—the ‘King’ who made the Abbey what it is today—Chicken Tikka Masala and the Abbey!

3 Replies to “Bath Abbey–A Storied History–Part 1”