Part 1 here

My kingdom for a wife (and an heir):

In the early 16th Century, Bath Abbey and England had a new king, desperate for an heir, married to a woman who could not give him a son.

Henry VIII, who had not expected the throne, was a carousing, hard-living man, tilting in yards, hunting, drinking and eating until late hours. And, he had a roving eye. Eventually, he decided that the first wife would not do, and to divorce her, he toppled the entire religious establishment in England.

Ultimately, Henry would have six wives, with a ditty to immortalize their fates: ‘Died, beheaded, died. Died, beheaded, alive.’

Prior Birde’s Chantry Chapel

A bit before Henry VIII, in 1496, came the appointment of a new Bishop of Bath and Wells, Oliver King. What King had inherited was an abbey inexorably crumbling into decay. And this had been the state of affairs for a good hundred years or so—in 1326, one of the Bath bishops lamented the ‘miserable state of his convent,’ and for many years the monks had been spending their money (presumably all those weaving riches) on revelry, and not maintaining the church.

The idea to rebuild Bath Abbey came to Bishop King on a visit to the church, when he came to swear in Prior Birde into his office in 1499.

That night (or so) King sat back on his heels after his long devotions and experienced a vision. He saw the Holy Trinity in a cloud and angels climbing a ladder to heaven. At the base of the ladder was an olive tree topped with a crown. Bishop King took this vision to mean that God was telling him to rebuild the abbey, in a quite direct message, because both olive (Oliver) and the crown (King) were in his name.

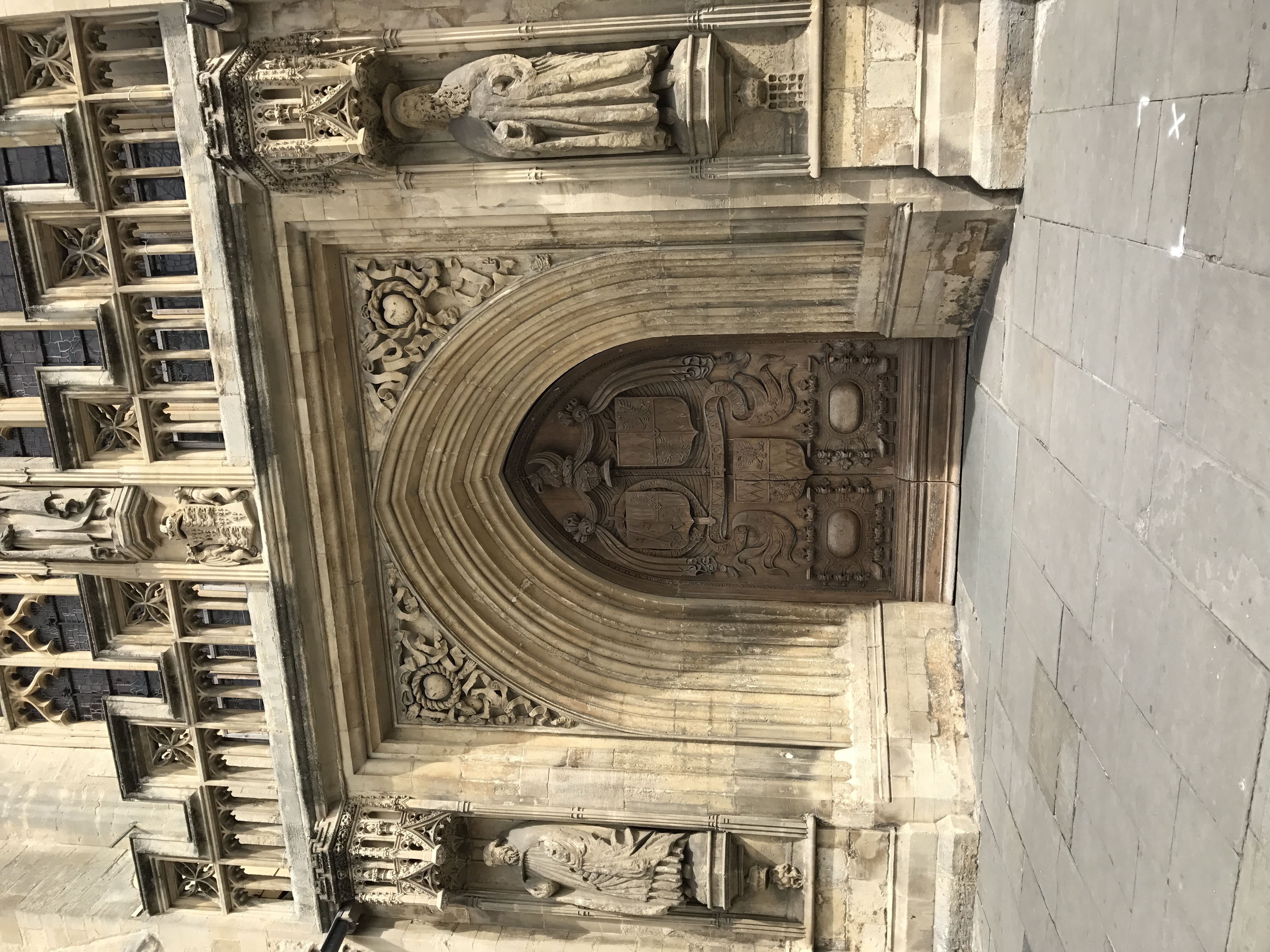

The front of Bath Abbey, the western side, was accordingly remodeled with Bishop King’s vision. On either side of the grand western window, on top of the main door, are the two ladders with angels climbing into heaven.

The West front of Bath Abbey, with the ladders on each side of the West window, and the angels climbing to heaven.

The rebuilding of Bath Abbey from its ruinous form was a long, hard, and costly affair.

This was no mere remodel or simple cosmetic improvements. Either the abbey was mostly demolished or King changed the plans and expanded it greatly, because he died before the ‘south and west walls were covered in, or even all the walls were raised to their proper height.’

It’s a somewhat bare statement for so extensive an alteration, especially since what Bath Abbey looks like today probably dates back to Oliver King’s vision—and not much earlier than that. In any case, King changed out the west front of the church completely.

The West door of the abbey

Prior Birde and his Chantry Chapel inside Bath Abbey

King had a helper, a man who oversaw the operations with about as much passion as he himself had, who was meticulous about details, and who nagged away at the workers to be clean, economical in their movements, to create something of lasting beauty. That man was Prior Birde.

If his name is familiar at all, after having visited Bath Abbey, it’s because, as a reward for all of his industry and diligence, Prior Birde allowed for himself—within the Abbey—a little stone-worked, wonderfully fretted little space. A chantry chapel. (I’ve talked a bit more about chantry chapels here, scroll down to Bishop Fox’s Chantry Chapel).

Inside Prior Birde’s Chantry Chapel

Prior Birde’s chantry chapel wasn’t all just pure vanity, it would seem. Not, for example, the indulgence of a wealthy bishop to leave his name and his likeness in stone for all posterity, so someone like I could visit, four hundred years later and think about him.

Prior Birde worked on Bath Abbey, and he not only oversaw the building of the church, but he very often dipped his hands into his own pockets to pay for the remodel of the church. To the extent, it is said, that Prior Birde died a poor man in 1525.

The work then continued under the auspices of another Prior of the abbey, Hollyweye, or Gibbs, who did not have the distinction of actually finishing the work on Bath Abbey, but his claim to fame instead was that he was—what was very loosely termed in the mid-16th Century—a chemist. In other words, since chemistry did not actually exist as a science, Prior Gibbs took money from unsuspecting people in return for giving them the Philosopher’s Stone, the Elixir of Life, the Universal Panacea, and presumably for turning base metal into gold.

We’re coming up on Henry VIII now, and the work on the abbey was still not quite finished. By this time, putting coffers of coins into renovating churches had lost its appeal. Henry VIII broke away from the Roman Catholic Church, and the heart just wasn’t there to finish the work anymore. In fact, around this time, the lead set aside for the abbey’s roof was stolen and some of the money was also drained and used for other, secular purposes.

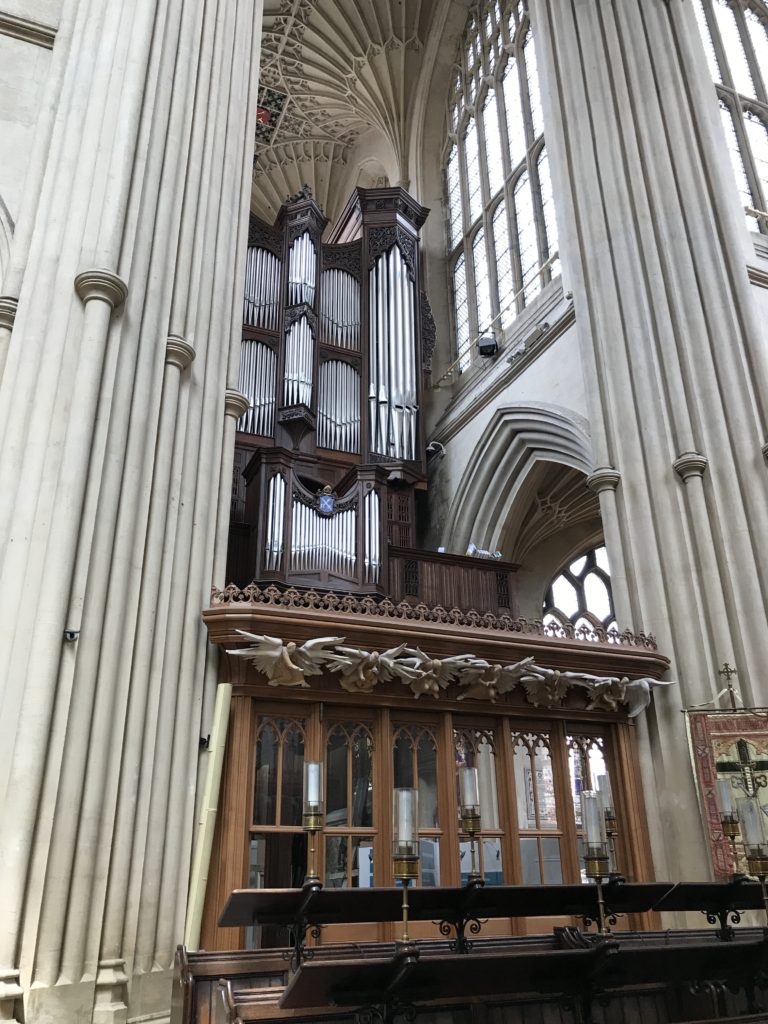

The Organ

And…Henry VIII and Bath Abbey:

The monastery of Bath was given up to the king in 1539, and ‘commissioners’ then attempted to sell Bath Abbey to the town of Bath for less than 500 marks—but the town refused. So, the abbey was broken up into its parts—glass, lead, iron, bells—and sold around town for the value of the scrap.

The church continued its existence somewhat woefully, and well after Henry VIII had died and his daughter Elizabeth I had become queen, there was more talk of its dire, neglected state.

Elizabeth becomes Queen of England:

In 1572, a local gentleman, Peter Chapman, applied to Queen Elizabeth I for money to renovate the church—she agreed, and sent out an order in the kingdom that a collection should be made. A new timber roof, covered in blue slate, then came to adorn the abbey, and a few years later the glass in the north transept, behind the organ, was glazed.

But, the work was s…l…o…w, incredibly so. By the end of the 16th Century, the south transept was still open to the skies (no roof there) and most of the nave was also exposed to the elements. Even so, the church was finally consecrated to St. Peter and St. Paul.

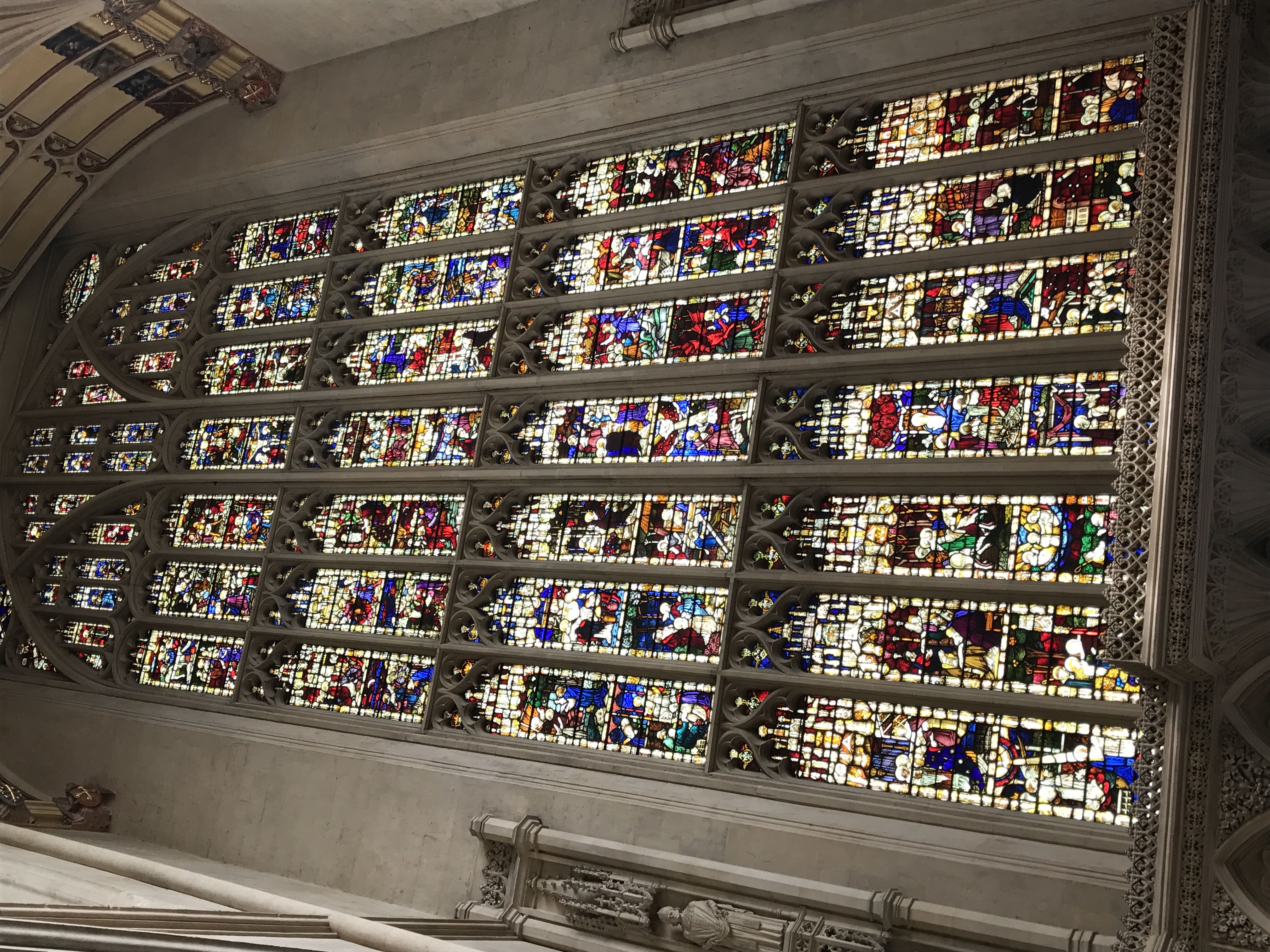

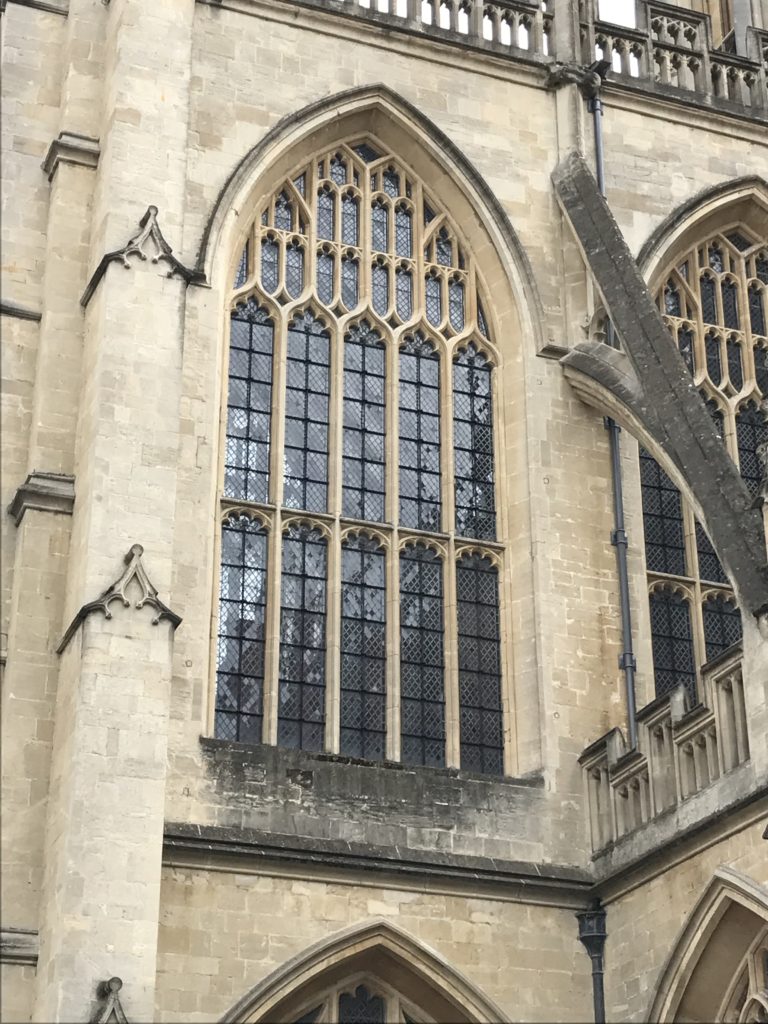

The East Window

Bishop Montague steps up…because he could not find a hotel near Bath Abbey:

Finally, and fortuitously, one of the wealthy bishops of the Church of England, Bishop Montague, was caught in a violent storm near Bath in 1608. The local squire, Sir John—instead of offering Montague shelter in his home—dragged him to the ‘shelter’ of the church and took him to the unroofed, exposed-to-the-wind north aisle of the nave.

“But, it rains in here,” said the bishop in consternation.

“Yes, your Excellency,” said the wily Sir John, “which is why your bounty is necessary to repair the church.” (Or something like that!)

That was enough, it would seem, for Bishop Montague to give a substantial sum—a thousand pounds—for the church to be finally completed, walls, roof and all. Turns out Sir John asked the right (and blindingly rich) person for help—the bishops in Queen Elizabeth I’s time had oodles of income from lead mines near Mendip, and money just lying around after they’d built and enjoyed their winter and summer palaces. Religion paid, it would seem, at least in those times.

Once Bishop Montague opened his hand, others followed, either to show their piousness, or to show off so they could be in Montague’s good books. The glazing, the roofing, the great west doors, and all other specific parts of Bath Abbey finally took shape, one by one, until it was more or less done—and much like it stands today—around 1621.

But…the Abbey’s still not complete:

With one difference. Over the years, buildings had sprung up all around the abbey, literally hugging the structure, built upon the outer walls, especially on the north side. The buildings—mostly houses—cast a gloom over the church, and as a consequence there was no actual view of Bath Abbey, from afar for example.

You came into the city, wandered through narrow, built-up lanes, and then the church loomed in front of you, with no gentle introduction, no sight of an elegant spire in the distance, no gradual, anticipatory entrance through the grand west doors.

Nothing of that sort.

About two hundred years after Bath Abbey was finished, more or less, in 1816 or so, one of the priests started agitating for the removal of these buildings and houses that so crowded the abbey.

Demolition work began and continued for a while, revealing Saxon coins, Roman baths, hidden rooms and other treasures. In one of the sealed-off rooms, workmen found two ‘empty’ chests, but supposedly one of them later became very, very rich and retired in great wealth. A-hem. Empty indeed.

The north front

The buildings crowding around Bath Abbey were so cut away—mostly from the built-up north side—leaving light and air around the church, and revealing its beauty for the first time since the renovations about 300 years ago.

It’s interesting to me that Bath Abbey is considered to have thus benefitted, because, as I pointed out earlier in this blog post (Part 1), it’s in the same courtyard as the Roman Baths (see my blog posts on the Baths, Part 1 and Part 2), and the area already seems crowded to me, especially in comparison to other churches and cathedrals with their cropped squares of greens (the ‘closes’) and their relatively solitary splendor.

It was another warm day when we visited Bath proper—the Abbey and the Roman Baths. Outside, in the courtyard, it was thronging noisy; a chatter of folks from all over the world; a young lady with a speaker at her feet singing opera (astoundingly well) with a hat in front of her for money; a juggler; a line forming in front of the baths.

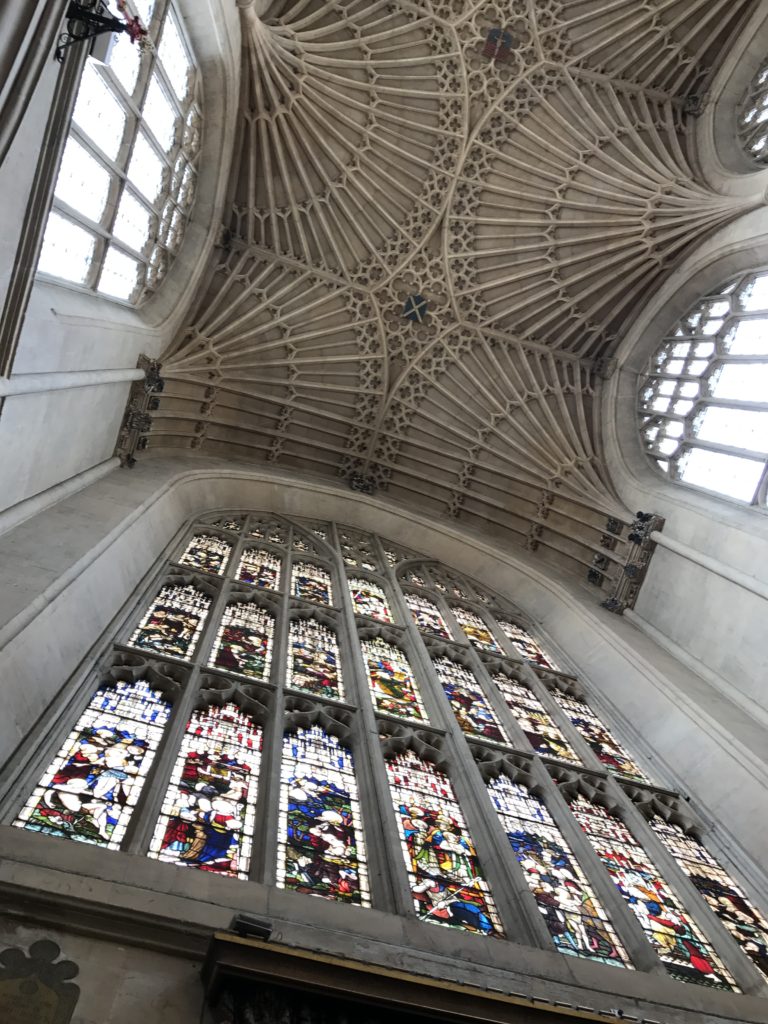

And then, we stepped into that quiet light and space of Bath Abbey and the world outside literally melted away.

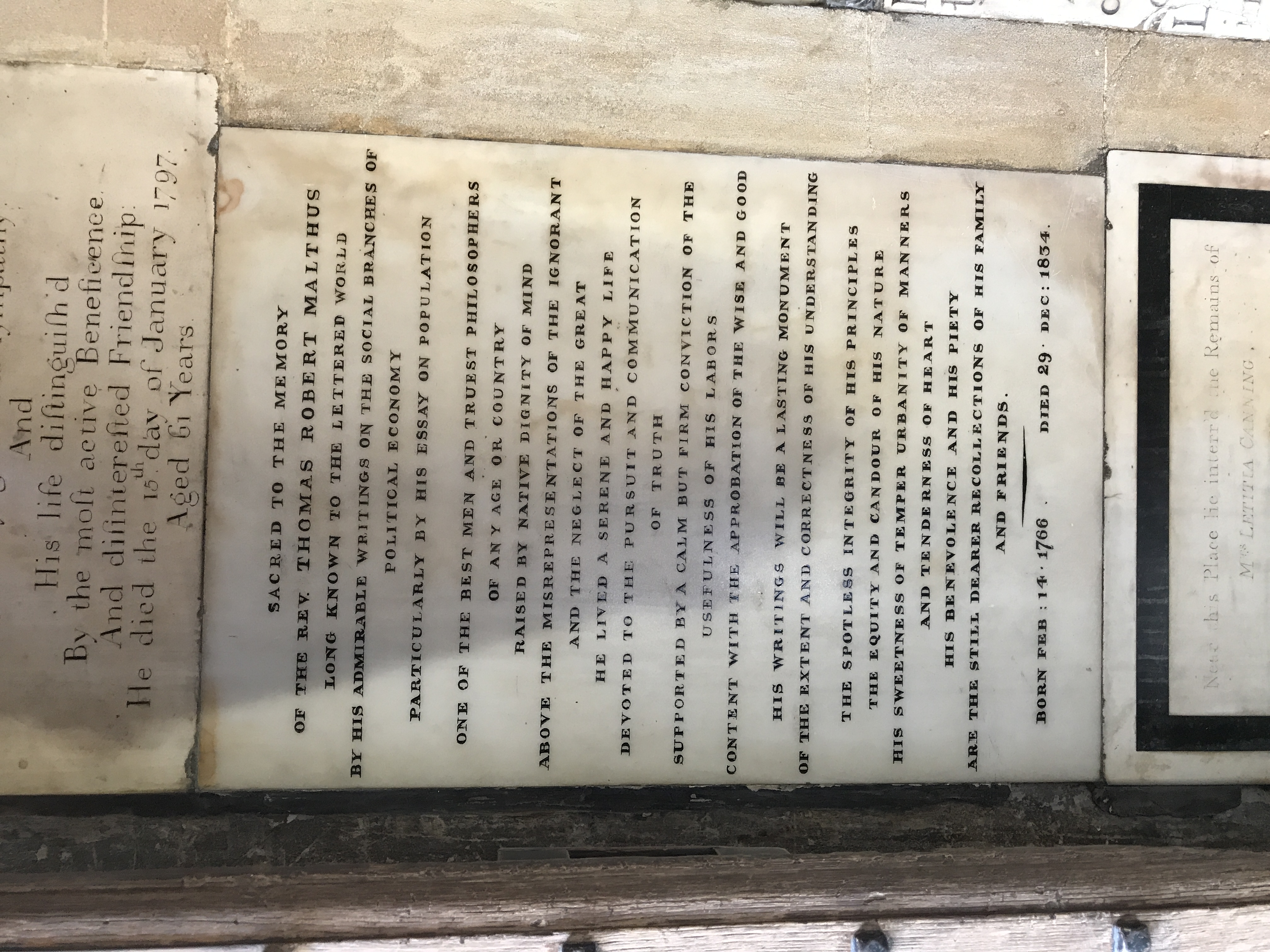

I’ll be honest, we’d already visited many churches and cathedrals; another one wasn’t on our list, but I wanted to pay my respects to Thomas Malthus, the economist, for what I might have been if I hadn’t become a writer. And so, we went to Bath Abbey.

The abbey is spectacular with all its centuries worth and layers of renovations, and had I realized where the memorial stone to Malthus was positioned, I might not even have stepped into the church.

Malthus is memorialized outside, in the little alcove leading into the church, to the left of the main west doors—which we discovered only after roaming around the whole church. And thankfully so. It was a busy day; we had places to go, things to see, and I’m not sure I would have wandered inside.

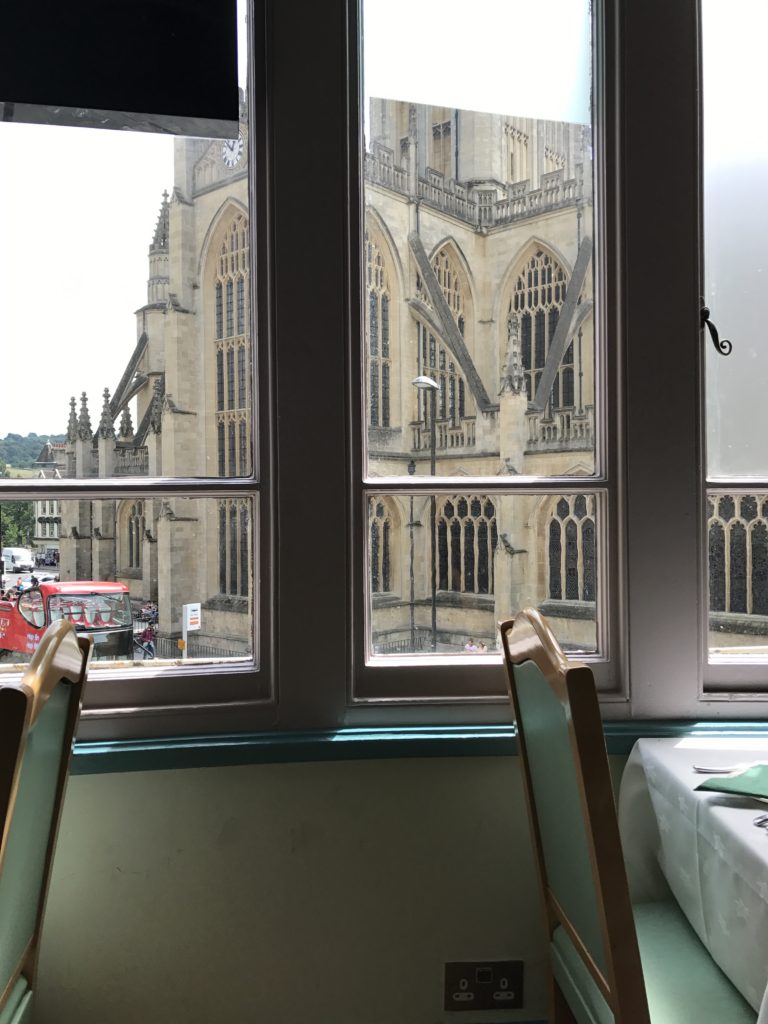

From the Abbey, we were off to see the bard in Stratford-upon-Avon. But first, lunch. If you’ve never been to England, you might not know that the national food there is…Indian. Truly. A chicken tikka masala—plated or sandwiched—is a permanent part of every pub menu (seems like), no matter where in the remote countryside. And the vegetarian option of saag paneer.

At the very least, those two.

But Bath’s a metropolis (sort of anyhow) and across the street on the north side of the Abbey we found this Indian restaurant where we had lunch. I’ve never been to an Indian restaurant with such a stupendous view.

And, the food wasn’t half bad either.

If you’ve enjoyed reading this, please consider sharing by emailing a link to the post, and by hitting the social media share buttons below, so others may read also. Thank you!

Keyword Phrases: When was Bath Abbey built; Bath Abbey Cathedral; Bath Abbey Ceiling; Bath Abbey England; Bath Abbey England; Bath Abbey history; Bath Abbey UK

On the next post—We go to southern India in quest of the ancient Chola dynasty—Ancient India–The Airavateshwar Temple–Legacy in Stone–Part 1

2 Replies to “Bath Abbey–A Storied History–Part 2”