Part 1 here

We’re on our (somewhat leisurely, I know!) way to the Airavateshwar Temple in Kumbakonam in southern India, built by the Later Cholas who ruled from the ninth to the thirteenth century. Later, because yes, there was the Early Chola dynasty in ancient India from the first to the fourth centuries, and a gap between these two during which the entire dynasty disappears from all historical story line.

In the first post, I introduced the Early Chola dynasty, because their reign—even that far back—is surprisingly well documented in more than two thousand poems written on palm-leaf manuscripts. (This is the oldest known history of south India.)

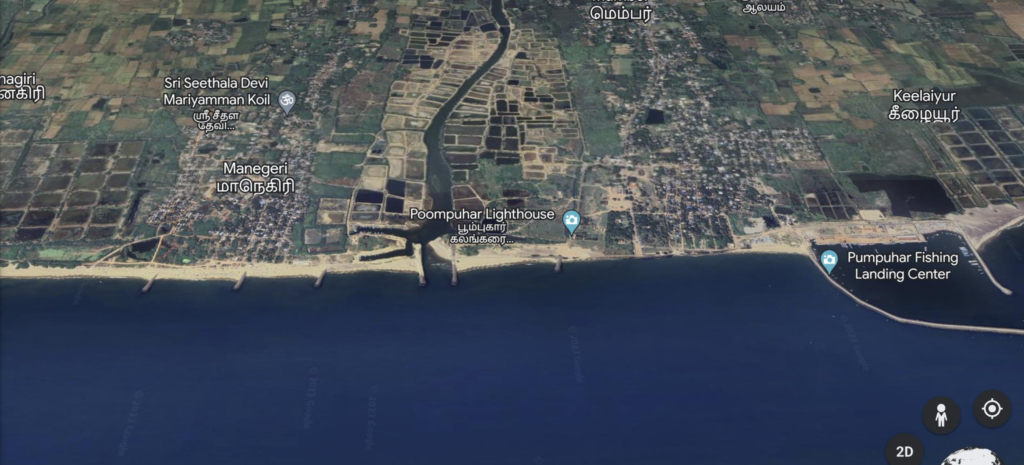

We visited the Early Chola dynasty King Karikala’s capital city at Kaveripattinam in the modern-day state of Tamilnadu, flitted through his palace, wandered down streets, stood at the docks at mouth of the Kaveri River, and marveled at the brisk trade and the mammoth ships from other parts of India and from Egypt.

So much for their lifestyle—what of the king? What of his duties, his responsibilities and his moral character? The Sangam Age literature of ancient India obliges even with that. Read on…

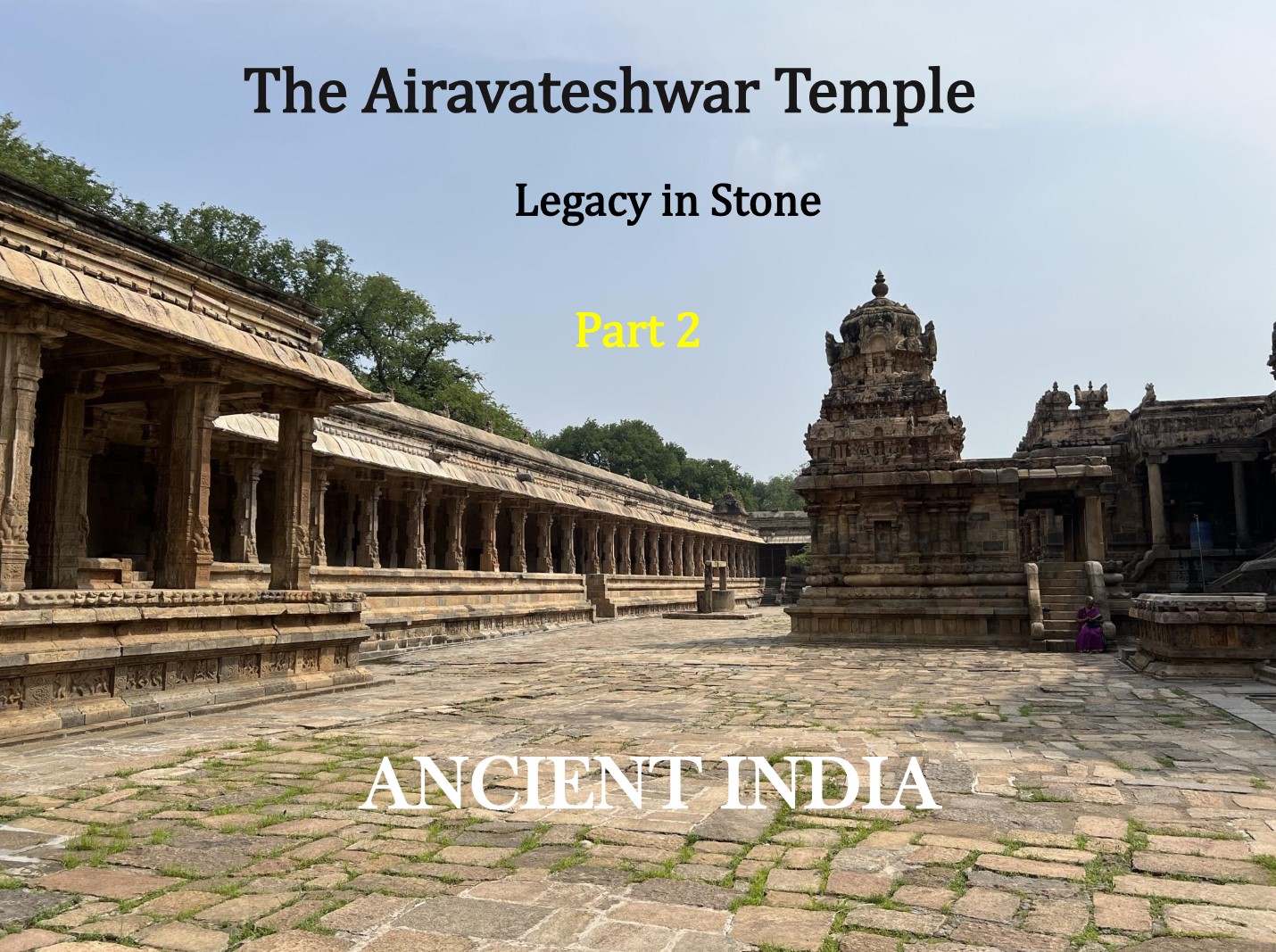

The 12th Century Airavateshwar Temple at Darasuram, Kumbakonam

Judge, devotee, soldier, sailor, warrior…prince?

In the Sangam Age poetry of ancient India, the Chola dynasty king, Karikala Chola, had to be all of these—in other words, he had to be just, upright, honest, benevolent, kind and charitable. Perhaps most importantly that last, for it was his hand that established the ‘sangams’ (hence the name of the time period) or colleges that housed, fed and sheltered poets in the land.

While most of the poets of these three most dominant kingdoms of south India (the Cheras and Pandyas were the other two) were men, one woman—Auvvaiyar—sometime around the beginning of the 2nd Century, not only composed verses from a very early age, she also enjoyed the patronage of many kings.

Despite her gender, her reception at the king’s palace was similar to that enjoyed by the male poet at Karikala’s court. In talking of her then-benefactor after his untimely death, she says that his generosity was boundless—if there was liquor, the king shared it while she sang to him; if there were guests, common or royal, he sat down to dinner with them, if arrows or lances were turned against her (his subjects), he shielded them. His death has knocked the bowl (food) from her hands, and from those like her.

It’s an almost constant theme in the poems, this, the ruler’s charity and liberality.

And, the poets were suitably grateful, in fact, at times somewhat fulsome in praise of their sponsor, as in this little verse about the Early Chola dynasty king, Karikala.

Thou art the Lord of the Kaviri whose floods carry fertility (to many a land)! This King is the lion of the warlike race of the Panchavas, who…has speedily scattered his enemies like the thunder bolt which smites whole broods of serpents. Thou art the warrior of Uranthai, where charity abides…

So munificent was King Karikala to these men of learning and talent, that a minstrel, upon coming to the palace, was immediately invited in, plied with wine in golden cups poured out by graceful and bejeweled handmaidens, and fed every day on rice, milk, and honey.

It all sounds great, but what’s that they say about too much of a good thing?

The minstrel soon tired of all this richness. He was picturesque in lamentation—‘our teeth became blunt and food and wine were no more welcome.’

He then asked to return home to his simple village life.

King Karikala was ‘displeased,’ but let him go, laden with gifts—lotus flowers to tie in the knot of his hair (by itself not a big deal; all guests were typically sent off with flowers), and pearl and gold necklaces for his wife.

But then, there was also a male and female elephant to follow him home, with their calves lumbering by, and an ivory-canopied chariot drawn by four striking white horses whose flowing manes had been dyed a bright red.

The mandapam, a pillared hall—used for gatherings—leading to the main sanctuary at the Airavateshwar Temple has a base carved with a horse and chariot on either side. Source

Lest you begin to think that the king has been awfully miserly, the final gift to the minstrel was a set of ‘well-watered villages!’

And all this because he had sung outside the palace gates, had been surfeited by the excess offered to him within the palace and had actually ‘displeased’ his host by rejecting his hospitality.

The minstrel had been abysmally poor before his visit to the king; no more, he now had enough wealth for several future generations.

It’s no wonder that King Karikala assumed an almost God-like influence over his chroniclers and his subjects. While they extoled, however, the poems also described the obligations of the king.

The primary duty of the Early Chola dynasty king in ancient India:

Our lady poet from the 2nd Century, Auvvaiyar, was bold enough to sing out a set of rules for an Early Chola king. She did this during a great sacrifice that the king was performing, and she had for an audience not just her patron but also two other kings. Sacrifices were common rituals in the Hinduism of ancient India, typically, a horse, a cow, a boar or a goat.

Auvvaiyar’s statue in Marina Beach in Chennai, along the long promenade of the beach.

So, here’s Auvvaiyar of ancient India, in full sabha, surrounded by ponderous ministers of court and the glitter of the throne room, confronting the awful majesty of three kings seated on golden chairs, and telling them how they should behave:

Be charitable (see, again that insistence upon charity!). Manage your anger. Give help when and where you can (charity again!). Let your subjects give alms (charity). Don’t talk of your own wealth (lest people expect charity of you?). Don’t be lazy. Don’t be ignorant (a king can hardly be illiterate when his subjects are not). Don’t beg (I’m making no wisecrack about this last).

I’m going to let myself be sidetracked a bit here, but not really, because this story about charity comes from the Ramayana (c. 400 BCE), very much this same time period in ancient India.

When the demon king, Ravana, decides to kidnap Sita, he comes up with a plot to send her husband, Rama, out of the way. But, Rama’s brother, Lakshmana, remains to guard his sister-in-law, and is eventually lured away also.

Before leaving, Lakshmana, with an arrow, draws a line in the dirt around the cottage and makes Sita promise that she will not leave the safety of this formidable circle.

Ravana kidnapping Sita, when he’s confronted by the eagle, Jatayu. Source

Soon enough, Ravana comes begging, disguised as a mendicant. So intrinsic was alms-giving and charity in ancient India (also true in many ways in modern India), that Sita comes out with a bowl of rice. She tries reaching over Lakshmana’s line to give it to Ravana, and he, realizing that this line—called the Lakshman Rekha—is too potent for him to defy, asks her to step beyond.

She resists; he berates her for being uncharitable, and she gives in. The moment she’s past the Lakshman Rekha, he takes her.

Both the Ramayana and the Mahabharata are powerful storytelling—and, in modern India, even today, the Lakshman Rekha is that…line in the sand, that step you must not take, that boundary you must not cross, that demarcation between right and wrong.

To come back now to our poet, Auvvaiyar, and her admonishments to three great and mighty kings in open court—there’s no record of how the kings took her advice. And all this, was very well in verse, but what did it actually mean?

The more you have in ancient India…the more is expected of you:

King Karikala, of the Early Chola dynasty, was a sovereign who was ‘born entitled to Kingship even from his mother’s womb,’ but also had no illusions that his monarchy could be sustained without effort.

He had two main means of wealth—agriculture and trade.

The former relied upon the Kaveri River that ran through his lands. But it was a tetchy, temperamental stream, flooding its banks regularly, destroying crops, carving out chunks of sand from the harbor and beaches at Kaveripattinam. (So, the Kaveri was in ancient India; today it is tamer, with dams on certain parts and a much more controlled flow.)

However, Karikala did try to subjugate the mighty Kaveri. He raised and fortified the banks, cut out canals to divert the water—especially in the times of the monsoon rains that swelled its flow—and diverted the excess toward the fields.

He was so successful that the yield from his land multiplied ‘a thousand-fold,’ and the poets, being poets, tell us the space that an elephant occupied when it lay down, gave enough grain to feed seven people.

The Hogenakkal Falls on the Kaveri River. Source

This was all very fine—it sustained the land, it gave his villagers occupation and made them self-reliant, and allowed him to look out of his palace at Kaveripattinam onto parks, green fields, birds and game, and trees flourishing in the distance.

The other, most common, source of income in ancient India:

It was his port, however, at the mouth of the Kaveri River, that brought King Karikala the most riches. He traded not only with other Indian kingdoms, but also the Arabs, and the Ptolemys—the Egyptian Greeks.

There were several godowns by the waterfront—warehouses where ships deposited their cargos and paid their customs taxes. Officers then stamped each piece with the image of a tiger (the symbol of the Chola dynasty), and distributed them to merchants further inland. So, the local markets were lush—fine horses from Arabia, and grain, agarwood, pearls, corals, gold and silver from different parts of India.

The mouth of the Kaveri River at present-day Poompuhar, where the ancient Indian city and port of Kaveripattinam was situated. Source: Google Earth

The Greeks brought wines, lead, brasses and glass for exchange, and when that did not suffice, poured their coins into Karikala’s coffers, because what they wanted in return was far more—pepper, cinnamon, tortoise shells, ivory, pearls, fine muslins, spikenard from the Ganges, betel nut, diamonds and rubies, corals and topazes.

The Greek merchants took all these goods home in a long and arduous journey. They departed from India sometime in December or January for their home port on the Red Sea, where the contents of their ships were laden on camels, hauled to the nearest point on the Nile, and from there, floated on barges down the river to Alexandria.

In my novel about the Kohinoor Diamond, The Mountain of Light, I’ve written about one such journey from India when the diamond is secretly taken to England. Even some fifteen centuries later, the only way the British could go back home was on this route–Bombay, Red Sea port, camels, Nile, barge, Alexandria, and from there, a ship across the Mediterranean to Portsmouth. This was the shortest route; else, they would have had to travel around the Cape of Good Hope.

Because Kaveripattinam was a thrumming hub of trade, the streets thronged with foreigners, absorbing local culture, disseminating it in their distant lands, and leaving behind impressions of their own traditions and customs.

The Greeks also absorbed elements of the local language, Tamil, and made it their own. They took back the Greek words for ginger (gingiver in ancient Tamil; zinziber in ancient Greek) and rice (arsi in ancient Tamil; oryzun in ancient Greek).

The stone Nandi, Shiva’s bull, on the ramparts of the Airavateshwar Temple in Darasuram, Kumbakonam.

One quarter of this port section of Kaveripattinam was inhabited by the Yavanas (foreigners), whose job it was to intercept ships from other parts of India and store their cargos in their own warehouses for the next ship that docked from Egypt.

And again, fifteen centuries later, when the British first came to India in search of very much the same items—spices, precious stones, brasses, and indigo—they also had ‘factors’ stationed at port towns to collect consignments for export to England when the next ship came in.

‘Factors’ because the barns in which the shipments were stored were called—at that time—‘factories.’

Despite the God-given right, the king who almost never was:

King Karikala was a warrior from very early on—so also was every ruler in ancient India. It was an occupational hazard, if you will.

His father had died while he was very young, and in the vacuum left by a powerful king, other claimants surged upon the throne. They seized the child and threw him into a fire. He escaped, but his foot was burned and charred. From then on, he was called Kari-kaal—Black Foot. Later, he reestablished himself on the throne with the help of an uncle, and then set about systematically establishing his kingship.

For the first few years, this meant going to war almost constantly. He fought and defeated an alliance of those two other powerful dynasties in southern India at the time—the Pandyas and the Cheras; he destroyed a confederacy of nine princes; he brought rival tribes into subjugation, and formed diplomatic relationships with the kings of Avanti, Vajra and Magadha. (See Part 1 of this post—these three kings sealed their friendship with Karikala by building and furnishing parts of his palace in Kaveripattinam).

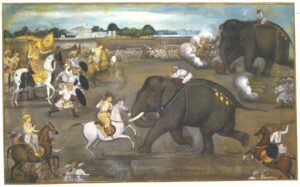

This painting is from the Padshahnama—about the Mughal Emperor (who built the Taj Mahal) Shah Jahan’s rule in the 17th Century. The battlefield of ancient India had prevailed much in character, troops, and animals used in battle later on. One major exception was the use of firepower, which did not come to India until the 16th Century. Source

Karikala was so successful at seizing his throne, holding on to it, and exercising his might over southern India, that one poet, describing a battle against a Pandya king, said that Karikala merely had to turn a look of anger upon that king and he fell in the battlefield.

Another poet—writing well after Karikala’s rule—claimed that he had conquered India up to the Himalayas (he hadn’t). But such was the supremacy of the king in the Sangam Age; one even claimed a descent from the gods, Vishnu.

My kingdom for a sword:

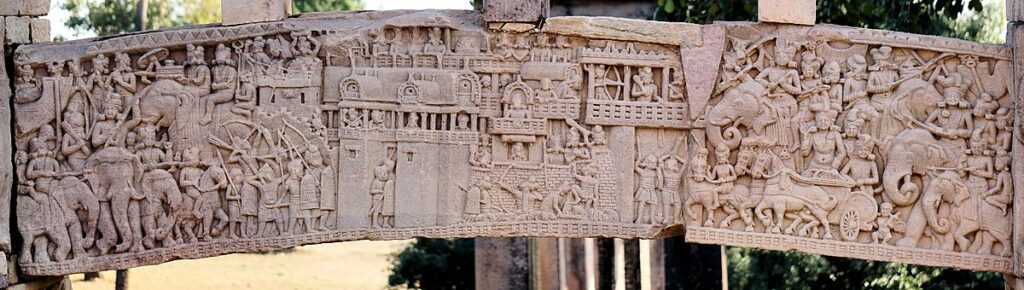

On earth, however, the Early Chola dynasty king, Karikala, preserved his power with a well-maintained and extremely well-regulated army, mostly infantry, some cavalry, a parade of elephants, but no sea power despite thriving trade—it was the Later Cholas who harnessed the vast seas around them and went into battle in far-flung lands across the waters.

Karikala was not just a figurehead ruler—since the kingdom was perpetually at war with neighboring feudal lords or the Cheras and Pandyas, he was also at the front of his army when they set out to fight. And, on the battlefield, when a king fell, the bearers of the standards, flags and royal umbrellas let fall their royal insignias, to signal to the vast army around them that they had been defeated.

Depiction of a battle at the Sanchi Stupa (c. 300 BCE). Karikala’s battlefield would have looked much the same—elephants, mahouts, horses, chariots, lances, spears, bows and arrows. Source

The king’s tent was a lavish affair—double-walled, staked to the ground by iron chains, with several rooms, the outer room guarded by the Yavanas and the inner room lit permanently by a bronze lamp in the figure of young maiden, standing and holding a cup in her hands which held oil and a wick.

This lamp is still used in Indian homes, more decorative now than functional, but it comes to us from ancient India. Source

The military camp at move, with its structured streets, its precisely laid out tents, its opulent interiors (at least, for the king and the nobles), its bazaars, its kitchens, its night-watchmen, its towers and guards, reminds me of similar encampments much, much later in Indian history—those of the 16th and 17th Century Mughal kings (best known for the Taj Mahal).

There are no photos or sketches of the Sangam Age literature military camps. Above, is an 18th Century or so Mughal encampment. There will be some similarity between the two, but they were essentially for different purposes. The Chola rulers used their military camps to house the army. A Mughal encampment such as this, above, would have moved the entire court from one city to another, depending on the seasons or the emperor’s whimsy—because the Mughal emperors had several capital cities and went from one to the other for their summers and their winters. Source

Still the same equipment, the same planning, the same movement of troops with the same attentive organization. The first Mughal emperor, Babur, however, brought gunpower to the Indian battlefield for the first time, and by the time of my Taj Trilogy novels, Mughal armies would have been, well…armed.

I wrote three novels on Mughal queens, see The Twentieth Wife, The Feast of Roses and Shadow Princess. In a later novel, set in a subsequent time period, the British in India use this same system of encampment when they are at move in India—my The Mountain of Light about the Kohinoor diamond.

Justice in ancient India:

King Karikala was also the supreme judge in his land. He had to be wise, unemotional in his rulings, and was held to the highest standard of morality and personal accomplishments. He gave audiences daily, showed himself to his people, administered the law of the land impartially, heard complaints and settled infractions.

The king’s daily audiences were called manrams, or sabhas, because he dispensed justice there. Since he naturally could not be called to arbiter every case in the land, villages and towns had their own manrams, usually held under the shade of a tree in the center of the village.

The temptation to stray?

With so much protection, so much wealth, and the chief of the revenue from land and trade, the Chola king was a mighty and powerful figure to his people.

But the burdens of kingship…these must have lain heavily upon one solitary man, surely?

And yet, there is little evidence of misrule.

Even if King Karikala’s palace was surrounded by the homes of his servants and bodyguards, (I mean, the courtiers were not nearby) he would still have had a trusted advisor to stay his hand against tyranny—his royal chaplain, a friend, a cousin, a minister, or perhaps even the uncle who helped him regain the throne.

The counsellors were all most likely men, but again, just like the lady poet, women played a vital—and equal, I think—role in society in ancient India.

The Chola dynasty is best known for two other most influential kings—Rajaraja Chola I and his son, Rajendra Chola I.

Their personal histories are formidable and so their names would probably have survived, but they also, each, left us two magnificent temples that we can visit today (one of those, the Tanjore temple, will come up on a future blog post).

Why do I mention these two kings?

Because their advisor was a woman, Kundavai. Who was sister to Rajaraja and so, consequently aunt to Rajendra, and they both leaned upon her wise counsel, and doubtless owed their prowess in conquest and diplomacy to her sage advice.

All work, and no play? How did a king amuse himself in ancient India?

The Chola king, brave in battle, wise in meting out justice, kindly toward his dependents, moral in character and bearing the burden of his decisions alone, had to be a model in his society and to his people.

It sounds like a very dull life!

King Karikala, with the enormous wealth flowing into this treasury from trade, had a veritable Fort Knox at Kumbakonam of his own. After taking care of the needs of his kingdom, he dipped into it for his own pleasures.

And pleasures, there were many.

In camp, at home in the palace, he celebrated religious feasts and festivals. The minstrel mentioned above speaks of encountering handmaidens in the palace—there were doubtless many, clad in silks, winning in their smiles, graceful in their manner.

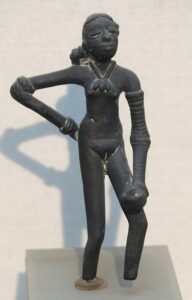

This is one of the world’s very first dancing girl statues, unearthed in the Indus Valley and dates to an astounding two thousand years or so before this Sangam Age (which dates to the 1st to 4th Centuries) of the Chola dynasty. So, this form of entertainment is as ancient as…well, as ancient can be. Every basic Indian history textbook will have this picture; mine did when I was in school and it fascinates me now as much as it did then. Source

Wines flowed, and so did meat. Brahmin priests ate and drank as did the others—there was no injunction against their eating meat or imbibing intoxicating spirits.

There was music in the palaces—on the yal and the flute. Lithe and nimble women danced, clad in flowing muslins, their anklets emitting musical tinkles of sound, their eyes outlined with kohl, their long hair threaded with the flame-like flowers of the kanakambaram.

Poets composed verses on the spot, and the soft thrum of a drum kept a mesmerizing beat in the background. There were parties in the gardens, heady with the fragrance of the night jasmine, and lovers stole away to adorn each other with the delicate blooms of the orange chethipoo.

Under an indigo sky, stars lay strewn on the earth, picked out in the fragile light of oil lamps all along the verandahs, and hung within the branches of the tamarind, the mango, the jackfruit and the coconut. The king’s cellars held jugs of liquor fermented with coconut water, palm fruit juice and sugarcane juice.

(Now, I’m having a bit of fun here in these above paragraphs in filling out some of the details, but I’m probably not that far from the truth.)

Detail from the Airavateshwar Temple in Darasuram, Kumbakonam, shows, middle, a flautist, at right a drummer, and on the left, a dancer.

There were also the women employed in the oldest profession in the world, who were courted (presumably) by the king and most certainly by the nobles, who kept mistresses about as easily as they kept their wives.

The wives, naturally, in the Sangam Age literature, hold the most honorable and preeminent positions, but the courtesans give them a run for their money, occupying chunks of storyline in the poems.

Two of the most famous Sangam Age epic poems:

The Silppatikaram is the story of a young couple, Kannagi and Kovalan, newly married and very much in love. But soon enough, Kovalan strays to a mistress and ends up spending all his wealth upon her. The long-suffering Kannagi takes him back and together they travel to Madurai to start a new life together.

Kannagi gives him one of her gold anklets to sell in the bazaar. The jeweler, thinking it to be the property of the queen, (who has one exactly like it), has Kovalan arrested. The king tries, and summarily executes him within just a few hours.

When Kannagi learns of her husband’s death, she wipes the kumkumam from her hairline (now that she is a widow, she can no longer wear vermillion), lets loose her hair, and storms into the royal palace with her other anklet.

Kannagi’s statue in Marina Beach in Chennai. Here, she is, ravaged by grief, holding up her anklet before she throws it down to break it open.

Turns out, the queen’s anklet is filled inside with pearls, but Kannagi’s has diamonds.

She flings her anklet to the ground, shattering it, and diamonds fly out. The royal couple is crushed, and penitent, but Kannagi’s anger has not abated—she destroys the city of Madurai in a great fire.

I’ve given you a very brief summary of the epic Silppatikaram, but it has a detailed and complex structure, and much space is given to the courtesan Madhavi’s character, her wiles, and her love for the feckless Kovalan. She also has a child by him, who figures in a later epic.

Courtesan-ship (for the lack of a better word) in ancient India was a fine art.

The women were all invariably beautiful, knew how to enhance their physical charms, had exquisite manners, could please almost anyone, moved with grace, were very accomplished in music, in singing, in playing instruments, and, in dancing. It was their life’s work.

And, it was during this Sangam Age in southern India that Vatsyayana (in northern India) wrote his Kamasutra.

The end is nigh?

And so, the Chola dynasty positively flourished for some three centuries, with their poets chronicling everything you’ve just read.

The Chola kings also made sure of their longevity through diplomacy.

Despite their almost-constant skirmishes, the three dynasties of the Cholas, Cheras and the Pandyas were wise enough to form marital alliances. King Karikala Chola’s daughter married the heir to the Chera throne and begat the next heir.

During the Later Chola period, when the line of direct descent was extinguished, the man who next came to occupy the Chola throne—and perpetuate the dynasty—found his way there through his mother.

All very good, but the poems now begin reflecting a different mood.

By the time the Manimekalai was written, probably a century or so later than the above-mentioned Silppatikaram, something is missing…the tone perhaps of supreme confidence in this Sangam Age.

Manimekalai is the sequel to the previous poem, and is the story of that illegitimate daughter of the good-for-nothing Kovalan and his mistress, Madhavi. The poet bemoans the extreme pleasures of his age, that death comes all too soon to all of us, and were we to spend our time in only pleasures—what value would our lives have?

Was that a sign of decadence? A loosening of morals? A sense of complacency?

Wherefore art thou, O Cholas!

If the Manimekalai is dated correctly—toward the end fourth century, it foretold the end of the Cholas, or rather, gave us a reason why. Because, at that time, the thriving Early Cholas just disappeared.

And then, nothing. Nada. Zip. Zilch…you get the picture.

The Cholas vanished from all chronicles and all histories for the next five centuries. It was not just the Cholas, the entire history of South India has a three-hundred-year gap at this point, no literature, no poetry, no temples, no palaces, no structures, no inscriptions in stone, no surviving oral tales to tell of what happened during this long-blighted night.

When the narrations resumed in the sixth and seventh centuries, there were three dynasties of rulers—the Pandyas, gamely soldiering on from the Sangam Age, and two others. But no Cholas yet—they don’t come into force until the ninth century.

And where had the Pandyas been for three hundred years? Who knows?

But when the stories began again, there were dark hints of wicked kings, the Kalabhras, who had decimated the three Sangam Age dynasties and held their kings captive.

Let’s pause a minute here. It beggars belief, held them captive for three centuries?

What are we talking about, something like nine or twelve generations of fathers, sons, cousins, uncles, and nephews, born and bred in the tradition of conquest, leadership and divine rulership, quelled for that period of time?

But so it was.

The courtyard of the Airavateshwar Temple, built by the Later Chola king, Rajaraja Chola II, with a view of the main shrine and the mandapam pillared hall, held up by two carved chariots and horses.

Naturally, the Kalabhras were an evil and powerful people, although no one knows where they came from or who they were—or, for that matter, where they went when the stories began again!

One thing was certain, while Buddhism and Jainism had been religions on the fringes of Hinduism before, they were now well-established, and one of the Kalabhra kings had been a patron of Buddhist monasteries.

(Several of the Sangam Age palm-leaf manuscripts—which have given us this rich history—were found in these monasteries, copied over and over again as time passed and the material disintegrated.)

And, what now?

South Indian history picks up again around the 6th Century, and the three prevailing kingdoms spend the next three hundred years or so in perpetual conflict with each other.

Still, no sign of the Cholas.

I’m writing a blog post on the 12th Century Chola temple in Darasuram, Kumbakonam, and here I am, having just finished off the Cholas by the fourth century.

How, and when, did they rise again?

If you’ve enjoyed reading this, please consider sharing by emailing a link to the post, and by hitting the social media share buttons below, so others may read also. Thank you!

Keyword Phrases: Chola dynasty; Chola dynasty architecture; Chola dynasty temples; Chola dynasty history; Chola dynasty time period;

On the next blog post—The Cholas come roaring back—and finally, leave an indelible mark in southern India—Ancient India—The Airavateshwar Temple—Legacy in Stone—Part 3

Thank you for this in-depth look at ancient India.

I loved learning about Our lady poet from the 2nd Century, Auvvaiyar.

She sounds like an interesting character for a future novel.

Ooh, yes, Janet! You’ve got me thinking. So glad you liked this.