We went to the Appomattox Court House National Historic Park by pure chance last summer. It was a lucky set of circumstances—a long drive, sheer boredom, trolling through the map app on my phone, and a name that popped up that sounded. . .familiar.

In these blog posts, we’ve taken a ramble through the end of the American Civil War.

Part 1 was the general introduction; Part 2 was about the Union Army commander (and future president), Ulysses S. Grant. Part 3 was General Robert E. Lee’s life, his childhood and boyhood, until he came to surrender at the village.

In Part 4 we followed the two generals after the fall of Richmond, over the last seven days of the war.

Now, we visit the village, so you can see what I saw that summer afternoon.

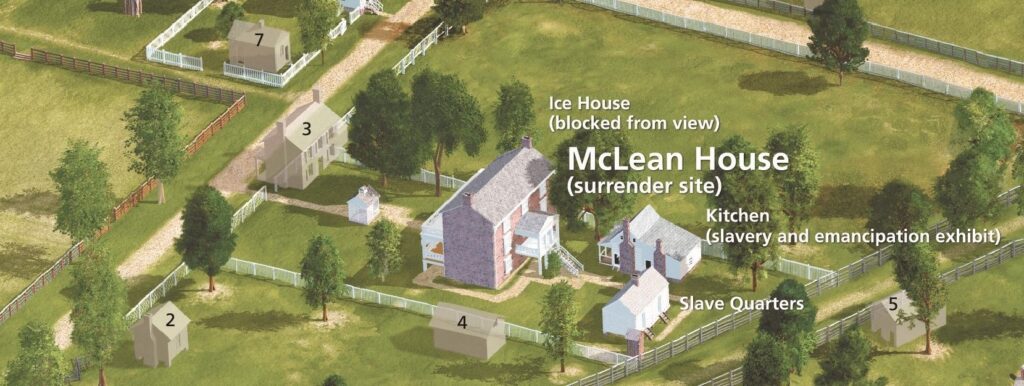

Appomattox Court House National Historic Park as it is today in a bird’s eye view. Of note, to start with, the red-roofed building (left center) is the court house. Bottom left near the parking lot is the McLean House where Grant and Lee met for the surrender and the end of the Civil War. Image Source.

We go way back now, to the first immigrants into the area:

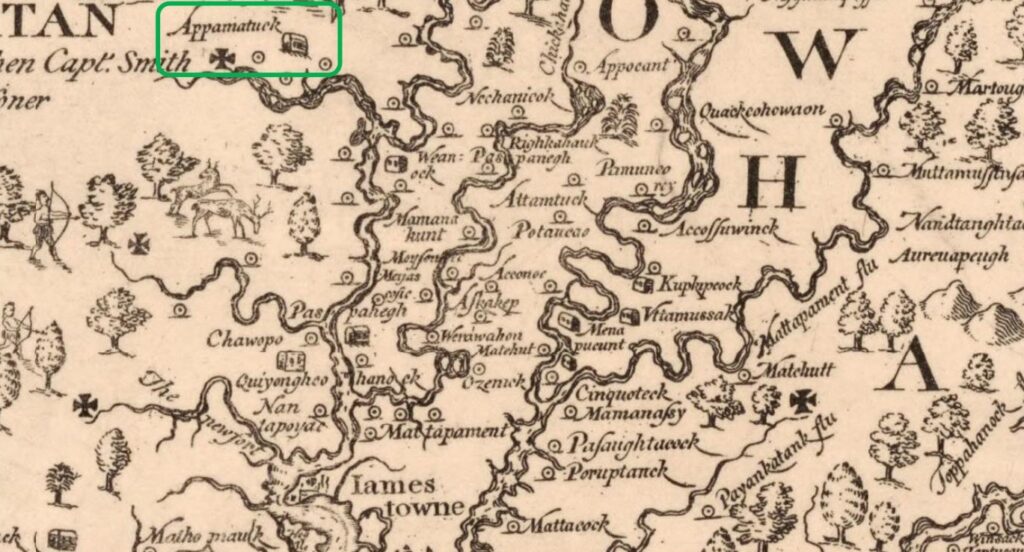

In 1606, Captain John Smith—one of the early travelers and settlers at Jamestown in Virginia—published a map of the Chesapeake Bay and surrounding areas. We’re at a bit of a distance from Appomattox Court House here. . .still, this is interesting.

Because the Appomattox River drains into the James River, and if you look at Smith’s map, there’s a Native American village on the top left (highlighted in green) called Appamatuck.

I think (it’s hard to tell) that the river below that is the Appomattox River meeting the James River. Smith hadn’t explored the Appomattox River very far obviously—but if the Appamatuck village is on the Appomattox River, then it was somewhere near modern-day Petersburg in Virginia.

A good hundred miles west of Petersburg is the village of Appomattox Court House, where Lee surrendered to Grant—more or less (if you’ve read Part 4 of this blog post) the same route that Lee took fleeing from Richmond, and Grant took, in chasing him.

A close-up view of John Smith’s map of Virginia in 1606, with the Appamatuck village highlighted. The Appomattox River comes from the west, flowing just above Appomattox Court House, the village where Lee surrendered to Grant. Image Source.

The Lees (of Robert E. Lee fame, see Part 3), the Washingtons (who eventually begat the first president of the United States) and other prominent families gravitated toward these parts about as early as Smith himself. They had huge landed estates and mimicked their back-in-England lives with balls, suppers, hunting, and of course, they were all in some sense farmers, or plantation owners.

There’s a whole country out there:

Tobacco was the produce of choice then. But it was a demanding crop—the hours were long in the sowing, weeding and harvesting and the work was back-breaking for the slaves and the indentured servants. Most of all, tobacco leached resources out of the earth, and the fields turned infertile after four years of growing.

So, the plantation owners and farmers moved out westward from Chesapeake Bay over the next century and a half after John Smith’s exploration.

As the land around the (soon-to-be) village of Appomattox Court House was developed, the farmers took their crop west twenty miles to Lynchburg for transportation to Jamestown in ferries down the James River, from where it could be shipped to remote lands for more profit.

As this tobacco trade flourished, other factors became important. Farmers and traders needed to conduct legal business, or vote in the elections, or get licenses, and often they would travel on indifferent roads and for very long distances, taking time away from their work and their potential earnings.

Meet the Pattesons, builders of the oldest structure at Appomattox Court House:

Two brothers, Alexander and Lilbourn Patteson (or Patterson in other records) decided to establish a stagecoach route on the 120 miles from Richmond to Lynchburg in 1809.

By 1819, they had built the Clover Hill Tavern on a ridge near the Appomattox River along the stage route. It was their headquarters, hosted weary travelers, gave them a good fire on cold evenings, and roasted meat and game for dinner.

No one lived there at that point, they had plenty of land around and they used it to build all the ancillary structures they needed.

A close up of the park map showing the Clover Hill Tavern and the outbuildings. Image Source.

Behind the tavern was a two-storey kitchen. Next to it was a small, single-frame building which housed the slaves who worked at the tavern. The dining room was attached to the main tavern (doesn’t exist today; marked a ghostly 12 on the map).

To the left of the tavern was another small building for extra guests that the main tavern could not accommodate—the guest house. Other original sheds and barns–which have long disappeared–were the carriage house (14), the mule stable (15) and the horse stables (16).

The Clover Hill Tavern and its outbuildings today. Front right is the main tavern. Behind, the two-storey building is the original kitchen, and to its right, the little white structure is the slave quarters. On the left is the tavern guesthouse.

By 1833, Patteson had a brisk trade in both his tavern and his stagecoaches. The coaches ran every day of the week excepting for Sundays from Richmond to Lynchburg, and they were pulled by four horses. Several other homestead owners along the route raised taverns of their own—which probably paid more than farming did.

One homesteader, thirty miles east, a Raine by name, took advantage of the stage route passing by his house. He called his place of business Raine’s Tavern. And then, the hamlet that sprung up around him came to be called by the same name. Raine’s Tavern.

Raine’s Tavern still exists on the contemporary map, east along the stagecoach route from Appomattox Court House. On the west is Lynchburg, on the James River. The stage route provided a more direct course to Richmond by land. Image Source: Google Maps.

Around 1836, or so, Patteson sold his Clover Hill Tavern to a John Raine and his brother Hugh Raine (who were, I think, brothers of the Raine’s Tavern owner). Hugh Raine also acquired 206 acres around the village, which was now called Clover Hill after the tavern.

In 1845, the Virginia legislature created the new county of Appomattox, whittling land for it from four surrounding counties, and establishing the county seat (and so, the court house) in Clover Hill village. They first built a jail on the north side of the stage road and then the court house itself in the center of the road, forcing it to curve around the structure on both sides.

The Clover Hill Tavern in 1865 and now. In the old picture, you can just about see the dining room attached to the main building, to its left. First Image Source.

A year later, John Raine sold the Clover Hill tavern and kept the land just beyond the court house and to the south of the stage road.

Here, he built another tavern and called it Raine Tavern. Two years later (perhaps business was so good in this tiny village that two taverns did not suffice) he built a large, two-storey structure in the backyard of Raine Tavern, and called it. . .Raine Tavern–this was the ‘new’ Raine Tavern.

By 1863, the Raine estate had sold both these Raine taverns to a man who came from two hundred miles away, who left the first tavern in its state of disuse and converted the second (newer) one into a family residence.

He had hoped to escape the devastation of the Civil War, only to find two famous generals in his front parlor, one accepting a surrender, the other tendering it.

That man was Wilmer McLean.

Wilmer McLean, the man who was at the right place, at the right time:

Wilmer McLean could very well have lived and died unknown in the chronicles of history, but that was not to be his fate.

He’d probably not thought much about fame; he must have thought himself well past the time to make any fame for himself. He was, in 1865, fifty-one years old, had several children, and was in a steady jog-trot way of life, certainly not expecting what was to happen.

Wilmer McLean in 1860. Image Source.

His father, Daniel McLean had been a baker and a sometime merchant in Alexandria for many years. He had amassed enough wealth to make him one of the city’s most prominent citizens.

And he used his influence to break away from his church and provide a house he owned on Fairfax Street for a new church, St. Paul’s Episcopal. He then gave money for land just abutting this house for the construction of a new church building, and in return, the McLean family has (even today) a pew dedicated to them at St. Paul’s.

Daniel McLean and his wife had ten children. Wilmer was orphaned when he was nine; his mother having died two years before, and his father following her soon after. Daniel McLean had left at least some fifty thousand dollars to be divided amongst his children, but not until they reached the legal age of twenty-one.

So, Wilmer was brought up by relatives, and went, most probably to the Alexandria Academy (around the same time as Lee, who was seven years older, and they would have overlapped by two or three years), where he went through the usual course of education at that time—mathematics, grammar, Greek and Latin and the art of writing well.

Wilmer moves up:

His first job, once he was eligible for his inheritance, was to invest in a grocery business. All men in Virginia between certain ages were required to be a part of a local militia—with light duties—and McLean rose to the rank of a major.

(John Raine, who bought the Clover Hill Tavern, and built McLean’s home, also had a military handle–he was a captain. So, it seems, most men had a military rank, even though they were not part of the regular army.)

McLean was an old thirty-nine when he married a very wealthy widow, Mrs. Virginia Beverly Hooe Mason, who could trace her ancestry and wealth through the Beverleys and the Hooes.

She owned several estates, and in an early version of a pre-nuptial agreement (called a settlement then), put all her property in trust for her own use and benefit the day before they were married. Then, the couple moved to her estate named Yorkshire, more than a thousand acres, mansion, farmland and slaves on the plantation, very near the Bull Run River.

It was a tremendous step up for McLean, even if he could not control his wife’s property, he could enjoy the income.

The ‘Yorkshire’ estate in Prince William County where the Confederate Army under General Beauregard set up its headquarters. Image Source: The Photographic History of the Civil War, Francis Trevelyan Miller, Editor-in-Chief, 1911.

For the next few years, McLean lived the life of a prosperous plantation owner. He and his wife had two children at Yorkshire, entertained their friends and family members, held the usual balls and parties and, living where they did, and as they did with their income dependent on slave labor, were strong Confederate sympathizers.

When the American Civil War began, in 1861, McLean ‘rented’ out Yorkshire to the Confederate Army—the outside barn became a hospital, and the mansion housed the surgeons and staff.

Even had he not adhered to the Confederate cause (unlikely; his entire extended family were as strong in their support), who would dare deny an army of soldiers? As it was, he was paid for his accommodations.

One of the first shells fired by the Union Army came through the wall of the log cabin on his grounds which was the kitchen. The McLeans were not in possession of Yorkshire at that time—they had moved away, leaving their house to the army.

The entryway of Wilmer McLean’s home at Appomattox Court House. The door to the left leads into the master bedroom. On the other side of the corridor is the parlor, where Grant and Lee met on April 9th, 1865.

The family never came back to Yorkshire, and, a year later, after the Second Battle of Bull Run, McLean bought a house in a village very far away, so he thought, from the war and unlikely to affect his family—in Appomattox Court House.

Unexpected guests come calling:

During the early days of April, 1865, even as Lee fled westward hoping to reach Danville, it was obvious to the inhabitants of Appomattox Court House and the neighboring villages that the Confederate Army was in a poor shape. For days, they had seen deserters from the army file through their neighborhoods, men who were living shells of what they had once been, starved, stick-thin, their uniforms in shreds, some without shoes, their shoulders hunched in defeat, their feet bloody.

McLean was out on the morning of the 9th of April, and so, he met Lee’s military secretary, Colonel Marshall. Who asked him for a suitable lodging for…what purpose he probably did not say.

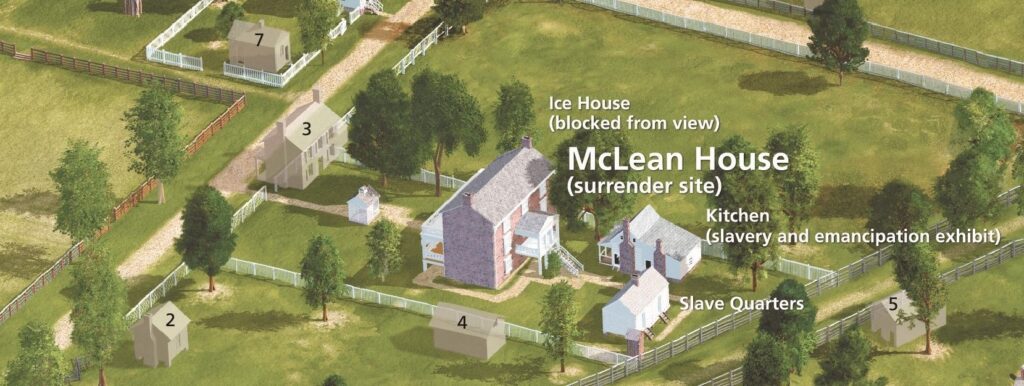

A closeup of the park map with the McLean House and its outbuildings as they were in 1865. Number 3 (ghostly) was the unused Raine Tavern—the first one (doesn’t exist anymore); McLeans’ residence was the second Raine Tavern. Image Source.

My guess, based on Marshall’s description of the building—dilapidated and unfurnished—was that McLean first showed him the original Raine Tavern (marked a ghostly 3 on the map above) which was in his front yard, and was an unused building at that time. It doesn’t exist today.

I think McLean would not have shown Marshall a barn or an outbuilding—or Marshall would have identified it as such. Nor would McLean have been able to—not owning it—show him another house in the village.

Appomattox Court House had the requisite court house, of course, the Clover Hill Tavern, a few law offices, a store, and a few other houses set away from the court house, but for the most part, the general description of the village was that it had very few buildings.

Marshall did not like the first choice. Then, either McLean offered him his own house, or, more likely, Marshall looked beyond the Raine Tavern to the large red-brick house—the best in the village, and said, how about that one?

Wilmer had had to ‘rent’ out his Yorkshire mansion to the Confederate Army at the beginning of the war. Now, at the end of the war, he could still not say nay to a Confederate colonel.

So, that one, it was.

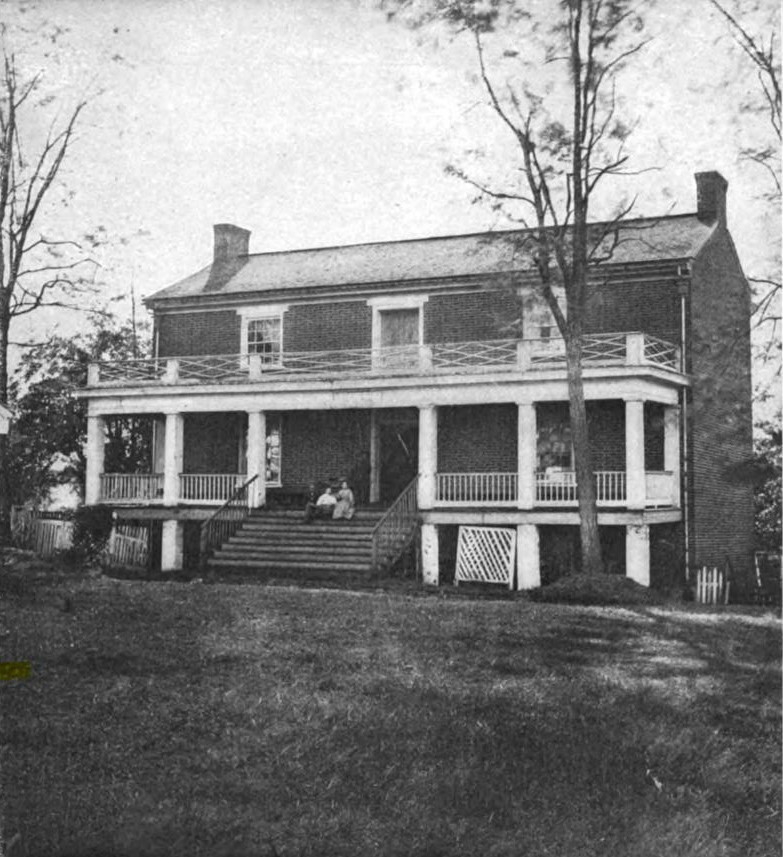

The McLean House, photographed just after the surrender in 1865. Image Source: The Photographic History of the Civil War, Francis Trevelyan Miller, Editor-in-Chief, 1911.

Briefly. . .the house and the village after the war:

The McLeans left Appomattox Court House two years after the end of the war. Over the next few decades, the home changed hands, with every new owner aware of its enormous consequence, and the weight of history upon it.

In 1891, a new owner came, with the intention of dismantling the house and rebuilding it on the stage of the 1893 Chicago World Fair. That work began, and it was painstaking, down to every outside brick loosened from mortar, washed, and put aside carefully.

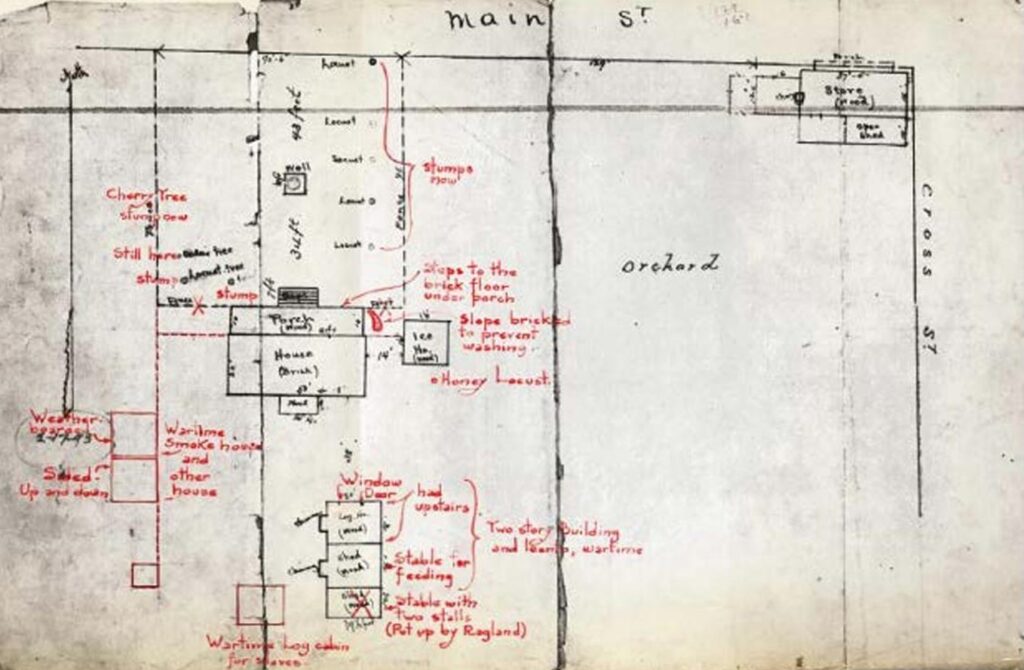

Door frames, mantlepieces, floorboards even, windows, details of paint colors—everything—was documented. Look at one of the plans drawn below of the McLean House.

One of the meticulous drawings of the McLean House site, on the outside. These later helped in reconstructing the building as it was that day in 1865. Image Source: Thinking Beyond the “Surrender Grounds,” by Josh Howard, for the National Park Service, May 2022.

But alas, the disassembled house, carefully packed, lay on the premises because the new owner had no funding to cart it away. The seasons passed, summer heat bleached the packages, and winter snows laid their cold hands over the remains of the house, until the courthouse burned down in 1892.

No one had the heart to go on at the village, it seemed, when the courthouse was moved to nearby Appomattox Station.

It wasn’t until 1940, when the Appomattox Court House National Historic Park came into being, that the authorities began to think about reconstructing the McLean House.

All those meticulous plans came in use now—paint, color, measurement of the rooms, designs on carpets, fireplace grates, the placement of the doors, windows, mantlepieces, the outhouses, the size of the structure, and where it had stood on the land.

This new McLean House, as exact as it can be to the original one, was completed in 1949.

A step back in time:

Grant and Lee met around 1:30pm on the afternoon of April 9th in this room (below), the front parlor. The house had originally been laid out as the second Raine Tavern, and so, the rooms were large, or at least, ran the whole width of the house.

There were two rooms on each floor and the house had three floors. The first floor, up a flight of seven steps and through a wide porch had the drawing room or parlor on the left and the master bedroom on the right.

McLean’s front parlor. Lee’s desk (marble-topped) is on the left, Grant’s wooden oval is on the right, and the carpet pattern and the sofa (not in the picture) have been reproduced faithfully. Image Source.

The furniture all belonged to McLean, of course, and Lee sat on the left, near the window looking out the front of the house, at a marble-topped table. Grant sat on the right in an office chair, and did his writing on that oval, wooden spindle-legged table.

A closer look at Lee’s marble-topped desk, and Grant’s desk, on which they signed the documents of surrender. And, the sofa against the doorway wall, with McLean’s daughter’s doll upon it.

During the signing and the during the some two hours that Grant and Lee talked, the room was filled with Grant’s officers and staff, who either stood around, or sat on the sofa against the front wall (where the entry doors were).

The master bedroom:

The other room on this first floor was a bedroom, the master bedroom presumably, because of the cradle. If McLean had moved his entire family here from Virginia, then he had with him two grown step-daughters from his wife’s first marriage, and his own son and two daughters, the youngest of whom would have been two and a half at the time of the surrender. (His wife was expecting another child then, not born until September, 1865).

The curators have done an exquisite job of recreating period furniture in the bedstead, the fire irons, the desks, the armoire, the quilts and throws, and that cradle—indeed all over the house.

The master bedroom on the first floor of the McLean House, opposite the front parlor where Grant and Lee met.

Knowing the inhabitants of McLean’s house at the time of the surrender, the placement of the cradle—front and center—seems a little. . .inconsistent with historical narrative. There was no infant in the house, I’d have placed the cradle against the wall, awaiting the baby in September!

The family poses for a photograph:

I was curious, so I zoomed in on the photograph of the McLean House taken in 1865—right after the surrender—to see if I could identify who was on the front steps.

Here’s what I’m guessing: the man on the left (light-colored jacket) is Wilmer McLean. Next to him, to his left, is his wife, Virginia Beverly Hooe Mason McLean. In front of Mrs. McLean is one of her grown daughters from her first marriage, and to the left of that young woman is the other daughter.

Their names were Maria Beverly Mason (twenty-one this year) and Osceola Seddonia Mason (twenty this year).

The McLeans on the front porch of their house in April, 1865. Image Source.

In front of Wilmer McLean is his eight-year-old daughter, Lucretia Virginia (born 1857). The little one on the steps is the youngest McLean child, two and a half-year-old Nannie Maury (born 1863).

I don’t know all this for a fact, but these were the people inhabiting the house at that time. The son, Wilmer McLean Junior (born 1854) is clearly not in this photo. Which brings us to the layout of the bedrooms on the second floor. . .

The first two pictures are of the bedroom over the master bedroom—the daughters slept here. The second two pictures are of McLean’s son’s room.

Upstairs, there are two bedrooms, one over the front parlor and the other over the master bedroom. These, to my mind, are laid out more logically.

Each adult stepdaughter slept with one of McLean’s daughters, so two double beds in a large room. The other room with just the one bed in one corner and the desk and chair would have been for McLean’s son (eleven years old in 1865).

We now go below:

The daylight basement level held the indoor kitchen—there was an outdoor one also in the backyard, where presumably, most of the roasting and frying was done.

The daylight basement kitchen (left), and the dining room.

This ‘warming’ kitchen inside would have been for the morning hot water and tea, maybe some gruel or porridge. And perhaps, every now and then, a fragrant bread baked in the oven—all the genteel stuff.

On the other side of the corridor in the basement is the dining room.

All the outhouses of a comfortable, southern family residence:

Wilmer McLean had slaves on his ‘Yorkshire’ plantation near Manassas and the First Battle of Bull Run. Here too, in Appomattox Court House, although he had no land and did not farm, he had slaves who cooked and cleaned for him.

A closeup of the NPS park map, with the McLean House and its current and former outbuildings. Image Source.

In the front of the house, there was a well for drawing water, and a well-house, a lattice-work structure covering it for safety. It stands today as it did then. It’s the small white square just behind the ghostly Raine Tavern (which is marked 3 on the map).

The McLean House with the well-house in the front yard—both are recreations of original structures.

There was also an ice house, as you see in the photo below—it’s the log shed to the left of the house.

(Right) The dark brown log shed, sunk into the ground, that served as the icehouse for the McLeans.

The ‘real’ kitchen was in the backyard—where the slaves did all the heavy cooking, roasts, meats, anything that caused billows of smoke and a sharp aroma of food.

The outdoor kitchen at the McLean House at Appomattox Court House.

And right next to the kitchen is a small single-frame house with two rooms for the slaves.

The slave quarters at the McLean House, next to the outdoor kitchen in the backyard.

These, above, are the buildings (I’m including the well-house) that have been recreated at the McLean House—five in all. There were three others: a privy, a smokehouse (ghostly 4 on the park map above) and the stables (ghostly 5 in the park map, behind the kitchen and slave quarters).

With a name like Appomattox Court House, there ought to be a court house?

And there is! Perhaps I ought to have started my tour of the village here, because it’s the first edifice nearest to the parking lot as you walk up the slope. But I began with the history of the place, and that begins (as I did) with the Clover Hill Tavern.

After the Virginia legislature created the county of Appomattox, paring land from four surrounding counties, they established the county seat here, in the-then village of Clover Hill.

In 1846, they built the courthouse right in the middle of the Richmond-Lynchburg stage route, compelling the road to curve around the square structure before it went on to pass the McLean House.

The courthouse is the Visitor Center today, and it’s not original, but recreated–still in the middle of the old stagecoach route. Image Source.

The first government building in this new county seat however, was the county jail, built in 1845 (ghostly 18 on the map above).

It burned down in December of 1864, so wasn’t there when Grant and Lee met in 1865 for the signing of the surrender. It was rebuilt in 1867 (marked opposite ghostly 18) and is one of the original structures in the park.

The 1867 jailhouse (left), and the courthouse, right. This is as you come into the village of Appomattox Court House from the east, from Richmond.

The original court house burned down in 1892 and the county seat was moved west to the town of Appomattox (current name); at the time of the signing, it was called Appomattox Station since it was a stop on the Southside Railroad.

The park, to preserve this village with a remarkable place in American history, came into being in 1940. And then, several buildings were reconstructed. The courthouse was one, as late as 1964.

The old courthouse in April, 1865, with the Union Army soldiers posing in front. And, the reconstructed new courthouse today. First Image Source.

For a while, the county seat was still called Clover Hill, but the name of the village soon came to reflect its purpose, and it became Appomattox Court House.

It was to tell county residents, who had to do all of their legal business in this building—no matter where they lived in the county—that this was the place where they would fight their legal battles, and vote. The idea of creating this new Appomattox county and its capital was to allow people the luxury of not having to travel more than 15 miles or so to conduct their affairs.

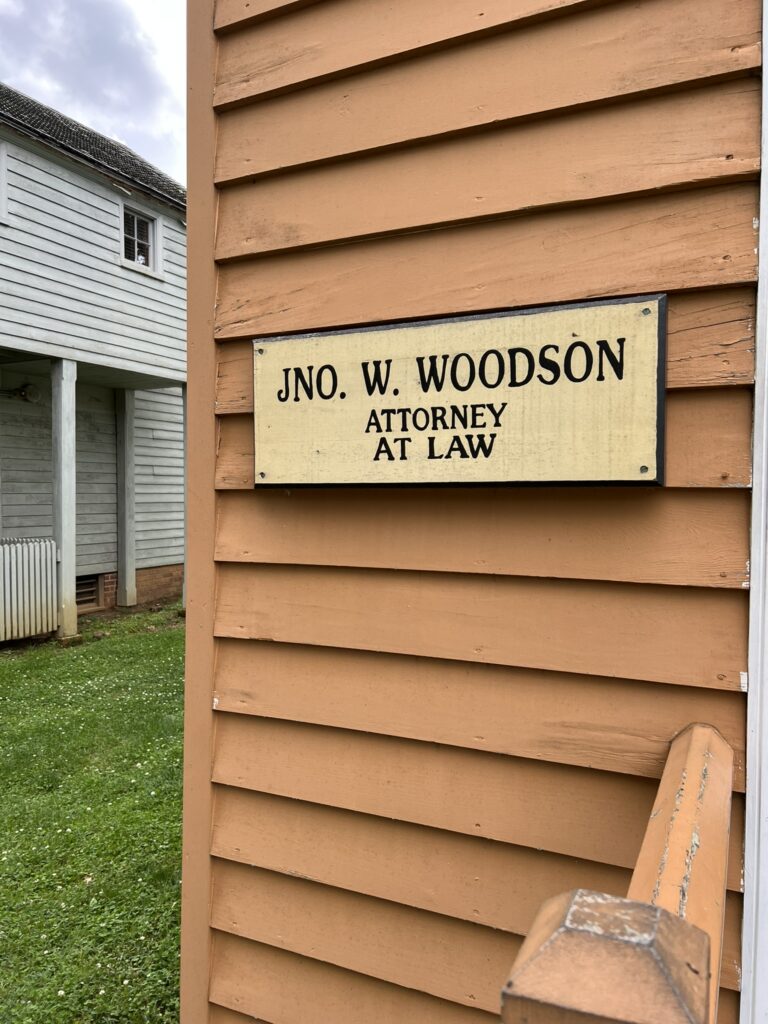

As Appomattox Court House became established, several lawyers set up shop in the village. Directly in front of the court house is another of the original structures, the Woodson Law Office.

The brown building is the single-room Woodson Law Office, near the village store (building on the left in first picture.)

John W. Woodson was one of the lawyers working at the court house and he rented this small structure from one of the original land owners around Clover Hill, and eventually bought it. But, while his office remained in 1865, he had died the previous year.

A village needs a general store, surely?

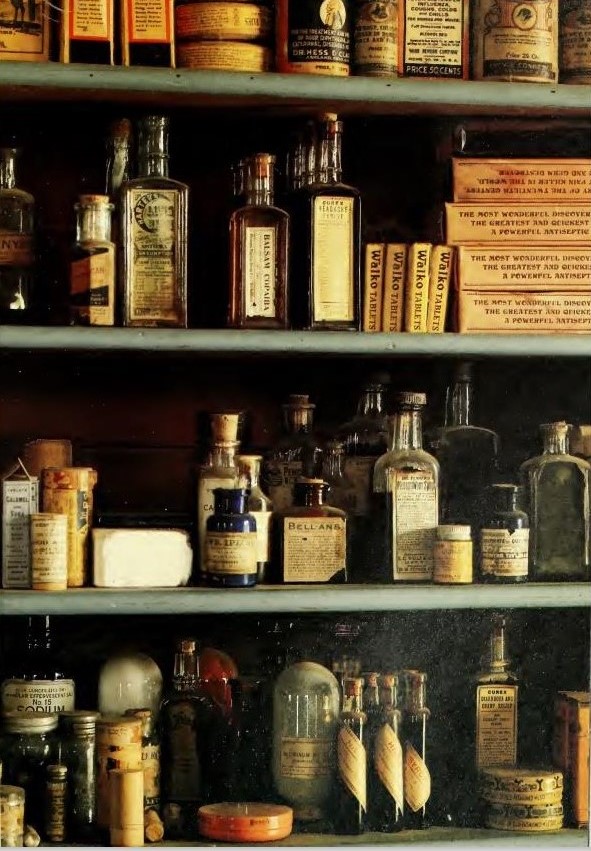

Right next to the Woodson Law Office is this larger building, also original, which is the Plunkett-Meeks store. The village store was also, typically, the post-office, and the store owner was the postmaster for the village.

The Plunkett-Meeks store (left) and the inside of the store. Second and third image sources: NPS brochure.

There’s not much information about either Plunkett or Meeks, but I think that the Plunkett who constructed this store was a David Plunkett, who was the village postmaster (so, aha, the owner of the store, surely?) and later a sheriff.

He owned the house in the park called the Peers House at the time of the surrender. And, we’re going to zoom out on the park map so that you can see the Peers House on the top (marked in a blue circle) and the general store opposite the courthouse (marked as the Meeks Store).

The Plunkett-Meeks store is circled in blue at the bottom, opposite Appomattox Court House. On the top of the map is the Peers House. Image Source.

We might as well take a look at the Peers House as it stands today—it’s also one of the original buildings in the park, but not open to the public.

Three other original buildings in the park:

There are three other original structures—the Kelley House, the Bocock-Isbell House, and the Mariah Wright House.

Another close-up of the park map, with the Kelley House (left), the Bocock-Isbell House (center), and the Mariah Wright House (right). Image Source.

The Kelley House is a small building on the south side of the stage route. It was originally built by Lorenzo Kelley in 1855, and during the Civil War his mother was alive and living in this house. Kelley and his four brothers all enlisted in the Confederate Army—two of them died, one deserted, and the other two were probably present when the surrender occurred.

In 1871, John Robinson, a freed slave, bought this house and reared eighteen children within its tiny confines. He was shoemaker and plied his trade from the basement.

The diminutive Kelley House.

The Bocock-Isbell House was one of the more substantial properties at Appomattox Court House when Grant and Lee met there. It was built about five years before the Kelley House by two brothers, Thomas and Henry Bocock.

The former was an attorney and eventually Speaker of the Confederate House of Representatives, and the latter was the county clerk.

Lewis Isbell was at the house during the surrender; he too was an attorney, but I’m not sure if he owned the house then, or was renting it from the Bococks.

The Bocock-Isbell House at Appomattox Court House.

The third house, also somewhat sizeable, belonged to a widow, Mariah Wright, at the time of the Civil War. It dates to the 1820s, when her farmer husband built the house. They had seven children there, some of whom enlisted in the Confederate Army.

The Mariah Wright House.

Time to say goodbye:

The Appomattox Court House National Historic Park had not been on our schedule that summer day last year. We had been on a long drive, I was bored, and swiping at the map on my phone when I found it. So, we arrived an hour before the park closed and sped about trying to see everything and absorb it all.

We met several curators as we zipped around, all of whom were extremely nice, and reminded us that the park would shut soon. However, we could stay on as long as we liked—the buildings would be closed, but the space was open.

Only, the parking lot would be barricaded, so we should move our car to the Confederate cemetery a mile away, and walk back.

We did, and for a long while after, as we wandered, we were the only people in that warm sunlight. I taped the blog video, we looked at everything leisurely, and then we went back to the cemetery to get our car.

As we drove away, I looked over my shoulder at the little village, basking in that amber hue like a sepia-toned photograph, with shimmering strands of mellow light filtering through the trees, casting an etched shade over the buildings.

It holds within its heart such an important slice of American history—which tells the tale of an America rent asunder, and the end of the war that patched it together, and made it whole again into. . .these United States.

If you’ve enjoyed reading this post, please share it, so others may read also. Thank you!

Keyword phrases: surrender at Appomattox court house; Appomattox court house date; who won Appomattox; battle of Appomattox court house; when was Appomattox; the civil war Appomattox; Appomattox importance; significance of appomattox; confederacy surrendered to the union ending the civil war; who surrendered at Appomattox Court House; Where is Appomattox.

Primary Sources: Campaigning with Grant by General Horace Porter, 1897; Lee at Appomattox by Charles Frances Adams, 1902; Various NPS brochures; The End of an Era by John S. Wise, 1901; Personal Memoirs of U. S. Grant, 1894; The Life of General Robert E. Lee by G. Mercer Adam, 1905; A Personal History of Ulysses S. Grant by Albert D. Richardson, 1885; Ulysses S. Grant by Owen Lister, 1901; Memoirs of Robert E. Lee by A. L. Long, 1885; Life and Letters of Robert Edward Lee by Rev. J. William Jones, 1906; Biography of Wilmer McLean by Frank P. Cauble, 1969.

On the next blog post—we return to India—Maryam’s tomb. Two of Emperor Akbar’s wives: The mysterious Maryam and the elusive Jodha—Part 1

One Reply to “Appomattox Court House–The End of the American Civil War–At the Village–Part 5”