The Bath years, the writing falters, but the research doesn’t

George Austen had had it by 1801. He had been rector of two parishes, Steventon and Deane, for thirty-seven years. He had conducted two, maybe three services a week at the two churches. He had visited the poor, the sick, administered last rites to the dying, and buried them in the churchyards. He had home-tutored pupils who had lived in his house year-round to prepare for the university. His wife had to be their de facto mother, and she had fed them, washed their linens, and tended to their fever and chills. All this, to make extra money to supplement George Austen’s income. Now, his children were grown up, some were married (Jane and her sister Cassandra were not, and were still at home), he was old(er) and in poor health, and he wanted to live the rest of his life out in a relative peace.

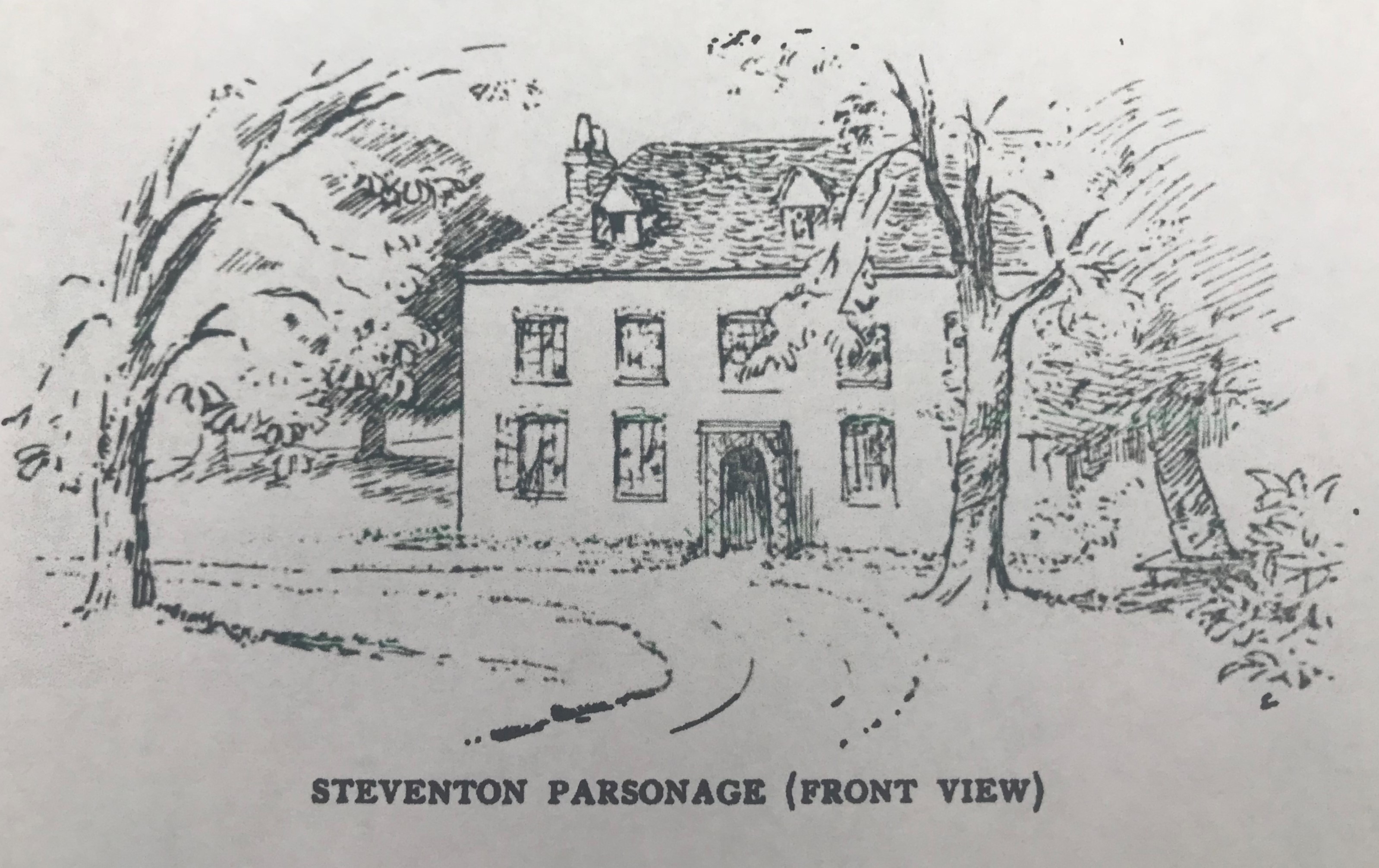

Steventon Rectory. The sketch is attributed to Anna Lefroy, Jane’s niece. Source: Jane Austen: Her Homes & Her Friends, by Constance Hill.

Cheerio, Steventon: Jane came home with a friend to the old rectory at Steventon from a walk one day, and was greeted by the news of the move. “Well girls, it’s all settled. We’re moving from Steventon to Bath.” Or something like that. It doesn’t seem to have been a topic that had been previously discussed with any seriousness between Ma and Pa Austen and the sisters Austen, because Jane Austen fainted immediately from the shock.

Reverend Austen transferred his duties to his eldest son James, who moved in with his family into the old rectory. (And two of whose children, Anna Lefroy and James Edward Austen Leigh, sketched the old rectory and wrote a memoir of Jane Austen respectively).

Jane had been born in the rectory in 1775 and was twenty-five years old when they moved to Bath. Steventon was the only home she had ever known. She must have realized that when her father died, either her brother James, or someone else would occupy Steventon rectory, but this—prematurely leaving Steventon for the ‘city’ of Bath, at least compared to the bucolic Steventon—was something she had not anticipated.

The Church of St. Nicholas at Steventon, where Jane Austen attended services. Blog posts on the church and Steventon Part 1 here and Part 2 here.

They seem to have moved almost as soon as the decision was made. In Sense and Sensibility, Marianne Dashwood wanders around her childhood home, Norland, just before leaving it forever for Barton Cottage, in another county. Marianne is the ‘sensibility’ of the title, sensitive, quick to flights of imagination, her heart touched by everything. Departing from beloved Norland (also the only home Marianne has known thus far) is a sad wrench, ‘when shall I cease to regret you! –when learn to feel a home elsewhere! –Oh! Happy house…who will remain to enjoy you?’ So, perhaps her author Jane (who perhaps prided herself on being more ‘sense’ than ‘sensibility’) also felt when she left Steventon rectory. Jane must have wandered around the house, the gardens, and the fields that she would definitely see again when she came to visit her brother James, but it would be someone else’s home, not hers anymore.

Jane kept busy in the interim—there was a lifetime of memories and things to pack and arrange at Steventon, and they didn’t quite know where they would eventually land in Bath, or if the new house would be as spacious as the rectory. The Austens had to bid goodbye not just to the land and the house, but also their servants, some of whom they had employed for decades. Jane mentions being happy when one of them has found further employment. And then there was the round of visits to their neighbors and friends, and the poor towards whom Cassandra and Jane had shown attention and compassion over the years.

George Austen had some work to finish at Steventon, Cassandra was visiting their brother Edward, so Jane and her mother made the journey to Bath by themselves, where they would first alight at the home of her uncle, her mother’s brother, Mr. Leigh-Perrot.

Camden Crescent today, down the street from the Paragon houses where Jane stayed upon first arriving at Bath. Source.

The Sojourn at Bath and fodder for another novel at Lyme Regis: Mr. Leigh-Perrot lived in the Paragon, a set of twenty-one houses. On the other end of the street was another set of townhouses set in the shape of a crescent, which Jane called Camden Place, and is today called Camden Crescent. This other end, Camden Place, was one of the most sought-after residences in Bath in Austen’s time, and the short time that Jane and her mother spent at her uncle’s house down the street, walking past Camden Place, gave her material for her novel Persuasion.

When our heroine, Anne’s father, Sir Walter Elliot, is forced to downsize and rent out his family estate to make up for all of his frivolous spending in the past, they move to Bath. Where in Bath? Why, no address other than the lofty Camden Place would do for Sir Elliot—because his author knew that it was the address that the fashionable gravitated towards in Bath.

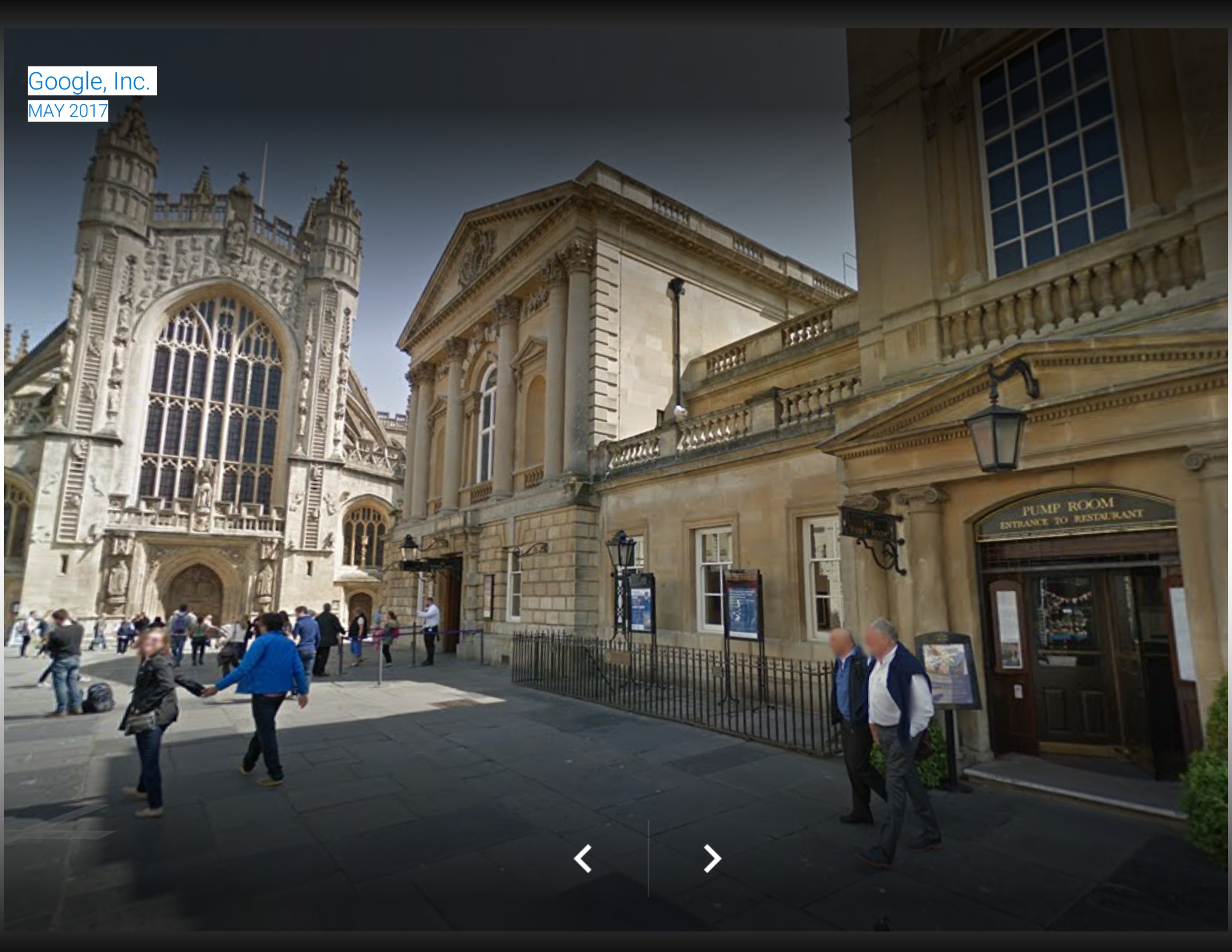

The Pump Room at Bath (right). To its left is the entrance into the Roman Baths, and the building straight ahead is Bath Abbey. Both the Roman Baths and Bath Abbey are in other blog posts. Source: Google Street View.

The days were busy. Jane walked down from the Paragon to the Pump Room in the courtyard of Bath Abbey with her uncle on most mornings, so that he could have a drink of the mineral springs water that Bath was (still is) so famous for. (Although today perhaps Bath is more known for Austen!) The rooms were always thronging with people who had come to Bath for their health, to drink the waters, to bathe in them (Roman Baths at Bath, Part 1 here and Part 2 here). You also came to see, and be seen. The women wore the latest fashions in jackets, gowns and headwear, the men strolled in their morning coats, nodding and bowing. The streets outside were filled with traffic—sedans, two-wheeled carriages, and equipages. The libraries did good business, being again not just places in which to check out books, but check out each other. Bath was, in other words, a year-round meet-and-greet and mating resort of sorts.

The difference from the sleepy Steventon countryside and rectory couldn’t have been more stark.

Musicians’ Gallery Bath Assembly Rooms. Source: Jane Austen: Her Homes & Her Friends, by Constance Hill.

Jane Austen attended the balls in the Bath Assembly rooms, and put the experiences into her novels, notably Persuasion and Northanger Abbey. The room were crowded, hot, and all the elegant, made-up ladies drooped. People danced and courted, chaperones played cards in other rooms or sat against the walls watchful of their charges, and everyone ran for tea and scones when the musicians took a break. Constance Hill in her Jane Austen: Her Homes & Her Friends sketched the musicians’ gallery around 1901. Nothing much has changed today; perhaps just the color of the walls, from when Jane visited, danced and watched all the gaiety in this ballroom.

The ballroom at the Bath Assembly rooms; the musicians’ gallery is to the right, above the door. Source.

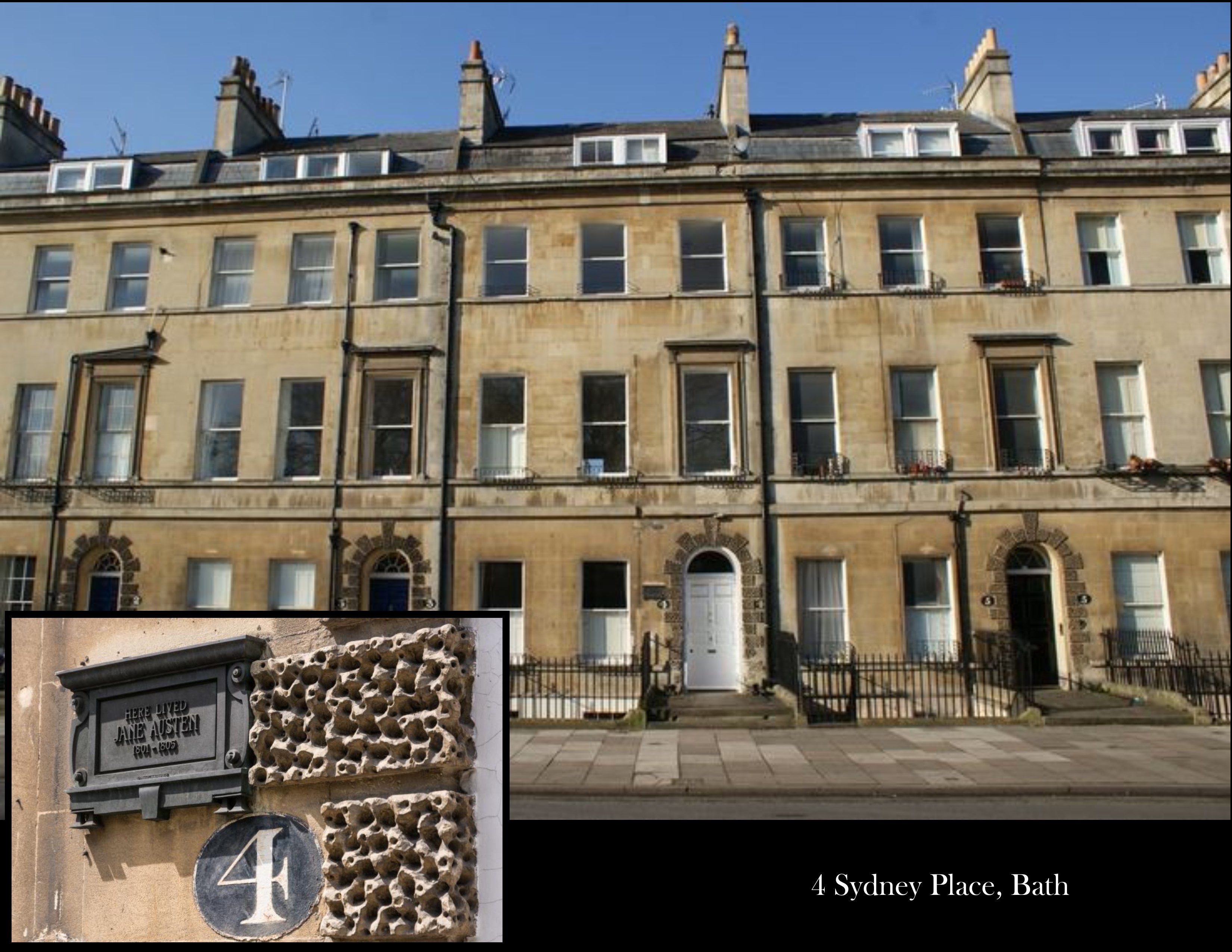

But, where did Jane live in Bath? As fashionable as Camden Place/Crescent was for the, um, fashionable, and while it was fine for Sir Walter Elliot in Persuasion, his author and her family could not afford to live in those elegant houses. They settled instead upon a townhouse, 4 Sydney Place.

For a moment, Jane had thought even that might be beyond their means. She had wanted to live near the Sydney Gardens, close enough to be able to go there everyday for a walk. As luck would have it, 4 Sydney Place was right opposite.

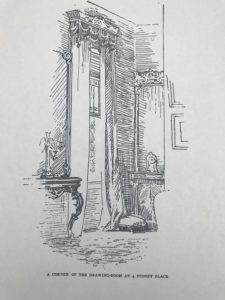

4 Sydney Place is the row house with the white door, and the scope of the house is to the left, two windows on the ground floor; three on the ones above. The windows above the door light up the staircase landings.

It wasn’t a mean house at all, quite large, in fact. The ground floor housed the dining room in the front, and a hall in which a staircase led upstairs to the drawing room. The kitchen would have been in the basement, lighted by the well of windows left of the front door and the rooms above would have held the parlor and the bedrooms. The corridor on the side of the staircase went through to the garden behind the house. The attractions, however, were all in front, in Sydney Gardens, where they had musical evenings under summer skies, with lights in the garden and the nights ending in fireworks. Even if Jane didn’t attend these festivities often, or went home before they ended, the situation of 4 Sydney Place was perfect. She went to bed with the glitter from the fireworks flashing against her bedroom windowpanes, and was lulled to sleep by their muted thuds.

Left, is the staircase leading to the upstairs rooms, directly ahead of the front door. Right is one of the windows from the drawing room, which was upstairs, above the ground floor dining room. Source: Jane Austen: Her Homes & Her Friends, by Constance Hill.

The move from Steventon had definitely been a blow, even as Jane enjoyed all the activity at Bath. The quiet was now gone and as a consequence, the Bath years were not really productive. She worked on the early parts of one book, The Watsons, which was still unfinished at the time of her death. Pride and Prejudice, Sense and Sensibility and Northanger Abbey all date to the Steventon years. She must have revised Northanger Abbey at least quite a bit after the Bath years, or perhaps during the Bath years with all of its Bath scenes. But the shock of the move, of leaving beloved Steventon and moving so permanently to another home, whatever it may be, definitely had some effect on Jane’s ability to write.

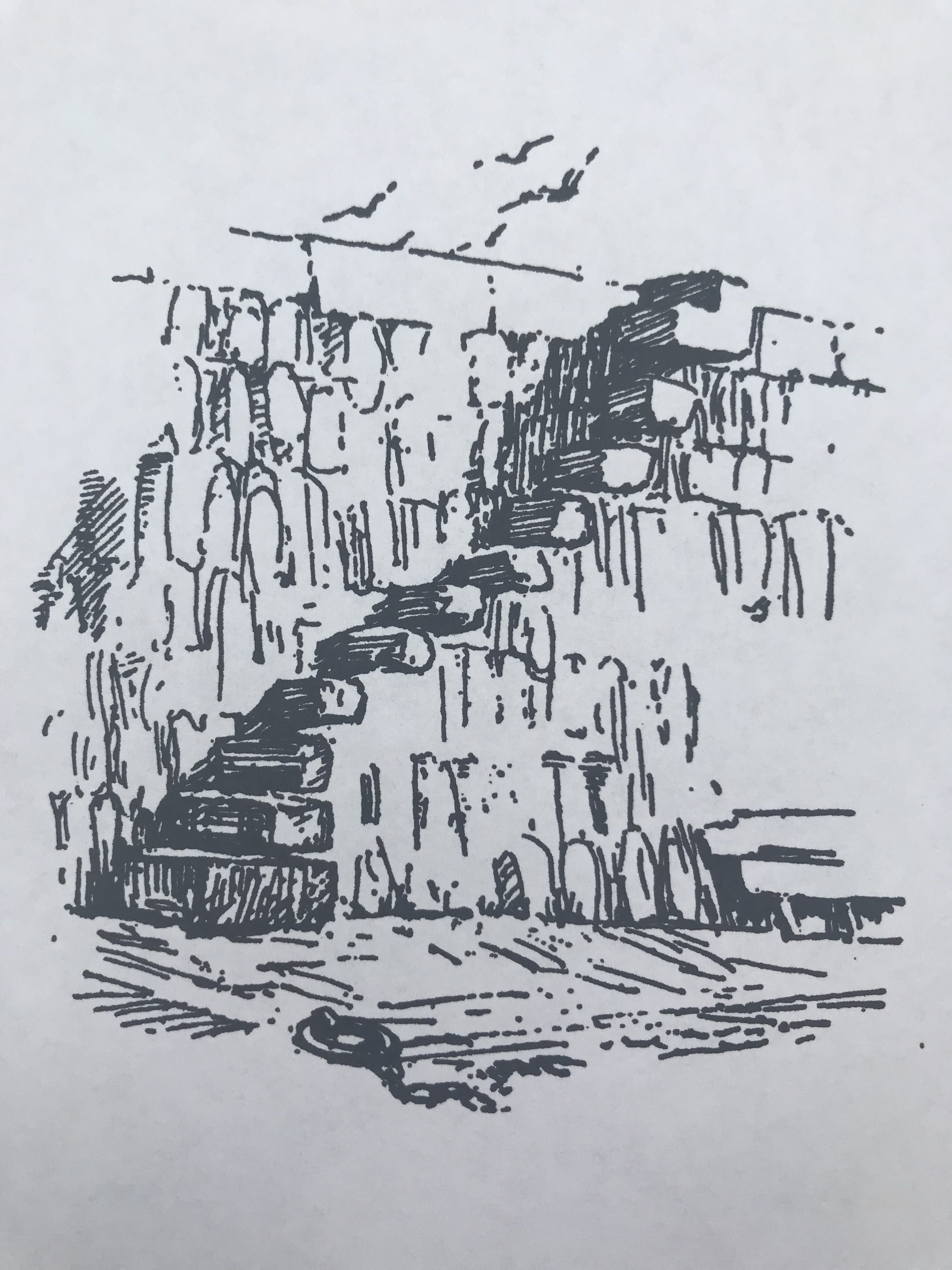

Another inspiration for Persuasion: Jane visited the seaside Lyme Regis in 1804. The town has an artificial harbor of stone arching around and into the sea, creating—within its sheltering arm—a safe harbor from storms for boats anchored there.

The Lyme Regis harbor is called the Cobb. Source.

The top of the wall is broad, with rough stone steps leading down. In Persuasion, Louisa Musgrove, that flighty creature who has captured Captain Wentworth’s attention for the moment, insists on jumping from the steps, over and over again. And once he puts out his arms too late, she jumps too early, and falls on the stone below. “…her face was like death.” Wentworth turns for help to Anne Elliot—the woman he had loved before, who turned his offer of marriage down, and who still loves him.

Lyme Regis Cobb Steps. Source: Jane Austen: Her Homes & Her Friends, by Constance Hill.

The Bath years come to an end: George Austen died in 1805, and was buried in the churchyard of St. Swithin’s at Bath, leaving the Austen women without one major source of income. For the next few months, Jane, her sister Cassandra and their mother wandered, given their uncertain finances. They had some help from Jane’s brothers, who all decided to augment their income, but still, they moved from lodging to lodging in Bath, and then to Southampton at the end of 1805.

There, they stayed with Jane’s brother Frank, then a navy captain, and his wife, Mary, in lodgings at first, and then a large, ungainly house in Castle Square. James Austen Leigh, in his biography of his aunt Jane, says that he had just begun to get to know her about now (he would have been about seven or eight years old). He visited this Southampton house, with its huge garden, at one end of which were the city walls, with steps leading up to the walkway on top and the lovely view all around.

Southampton City Wall. Source: Jane Austen: Her Homes & Her Friends, by Constance Hill.

The house was the property of the owner of the castle of Castle Square, the Marquis of Lansdowne. The castle in the square was imposing enough as a building but with little space around, since it was in the middle of the city. And so, from the windows of this home, James watched the Marchioness ride out of the castle in splendor in a little phaeton drawn by six or eight little horses in perfectly matched pairs, their colors darker near the top of the reins and lightening (in pairs) away from the groom. It’s a wonder that Jane didn’t put that into one of her novels!

The Bargate was the main gateway into Southampton Castle. The castle that the Marquis of Lansdowne built—and that Jane must have seen—doesn’t exist anymore. Source.

In 1809, Edward Knight, Jane’s brother, offered them a more permanent home in one of two places—either near his seat at Godmersham Park in Kent, or near his sometimes residence of Chawton House in Hampshire. They chose Chawton Cottage near Chawton House, and so, Jane Austen returned to Hampshire, only fifteen miles from the old rectory at Steventon. And here, she would stay until she died.

If you’ve enjoyed reading this, please consider sharing by emailing a link to the post, and by hitting the social media share buttons below, so others may read also. Thank you!

On the next post—how Chawton Cottage came to be Jane Austen’s home—her brother Edward Austen becomes the rich Edward Knight—At Home at Last: Jane Austen in Chawton Cottage—Part 2

Extremely informative. Have read about Jane Austen ‘s life and works on internet but your article provides interesting facts along with the pictures and sketches making it more interesting.

Thank you! I’m trying to put together the blog posts the way I would like to read them–I’m glad to hear it works.

Beautifully detailed account of Jane Austin’s life. Thank you for the descriptions along with the drawings and photos that made me feel as if I was there.

Janet

Thank you, Janet! So glad to hear you enjoyed it.

Enjoyed reading this very much. I have not read Austen’s biography, except whatever is attached to her novels, so it was informative.

Thank you! I’ve read plenty of Austen biographies over the years, but writing the blog and researching her life was something else.