We’ve arrived at the stage of our Akbar-Maryam-Jodha saga, where Emperor Akbar has married his fourth and most significant wife, Maryam. Significant, because she gave birth, in 1569, to his first surviving son and heir, Prince Salim, who went on to become Emperor Jahangir. But, what of Jodha, also Akbar’s wife?

That most-beloved and favorite Hindu wife, was she Maryam? Or, was she another wife, so adored that Emperor Akbar neglected all his other wives for her? What of their grand, grand love story—what about all the movies made about her, the television series that star her?

More to the point, was there ever a Jodha Bai in Emperor Akbar’s life?

Well. . .there was a ‘Jodha Bai,’ sort of, in the imperial Mughal harem, but, she was only indirectly connected to Akbar. I don’t mean to confuse; let’s investigate this further.

A look at the etymology of those words ‘Jodha Bai:’

Simply put, Jodha Bai is more of a title than a name. ‘Bai,’ is the honorific for a Hindu royal woman, a princess or a queen, or even someone connected with the royal family of a lower rank.

As for Jodha? It means a princess of the Rajput kingdom of Jodhpur.

This fort, on a hilly eminence, is the Mehrangarh Fort at Jodhpur. It was built some hundred years before Emperor Akbar came a-conquering. The city, the kingdom then, was called Jodhpur after its founder. A Jodha. Yes, there was a male Jodha, who gave his name to Jodhpur. Image Source.

None of the histories from the Mughal age—that is, none of the Mughal historians—mention a Jodha Bai as Emperor Akbar’s wife. Because, he did not marry a princess of Jodhpur.

Akbar did marry three Hindu princesses. The first came from the princely kingdom of Amber (she went on to become our Maryam, mother of Emperor Jahangir), and I detailed her history in Part 2 of this blog post. We do not know her Hindu/birth name, but do know a lot else about her family’s origins, the men in her family, their positions at court, and the wealth and status they amassed when she became Akbar’s wife.

Emperor Akbar also married two other Hindu princesses—most likely in 1571 (Maryam became his wife in 1562). Again, these two women are nameless in Mughal histories, but recorded are the names of one’s uncle and another’s father.

One wife was the niece of Rai Kalyan Singh of Bikaner, and the other was the daughter of Rawal Har Rai of Jaisalmer.

So, as far as historical documentation attests, Emperor Akbar married the princesses of Amber, Bikaner and Jaisalmer. Not Jodhpur. There was no Jodha in his harem.

So. . .Akbar did not marry a princess of Jodhpur, eh? No, but his son, Jahangir did!

Akbar’s army conquered the Jodhpur kingdom around 1561—just before he married Maryam, and remember, Maryam was his first Hindu wife. While Jodhpur swore fealty to him, Akbar’s sentiments did not turn toward matrimony with this kingdom, and he did not choose a wife from here.

The ruler of Jodhpur, Chandra Sen, was at loggerheads with the Mughal Empire for many years, and Akbar gave Jodhpur to his brother-in-law, Rana Rai Singh of Bikaner, to govern. (Rai Singh’s cousin was Akbar’s Bikaner wife—the two men had yet another connection, but I won’t talk of that here. Suffice it to say, they were twice connected by marriage).

Eventually, Akbar gave Jodhpur back to another scion of the Jodhpur royal family, Udai Singh, known as the ‘Mota Raja,’ the fat king.

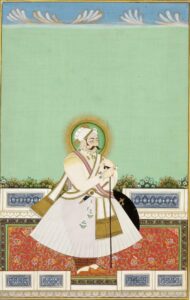

Rana Udai Singh of Jodhpur, one of Emperor Jahangir’s fathers-in-law. Mughal painters were fairly accurate in their delineations, and did not idealize their sitters. Well, maybe they did with the royal family, but this is Udai Singh all right, in all his. . .um, avoirdupois, which earned him the sobriquet of the ‘fat king.’ Image Source.

And then, he arranged the marriage of Udai Singh’s daughter, Jagat Gosini, to his son, Emperor Jahangir in 1586. (Jagat’s one of the main protagonists in the first novel of my Taj Trilogy, The Twentieth Wife. Because Mehrunnisa, Jahangir’s twentieth wife, wrestles power away from her upon stepping into the harem.)

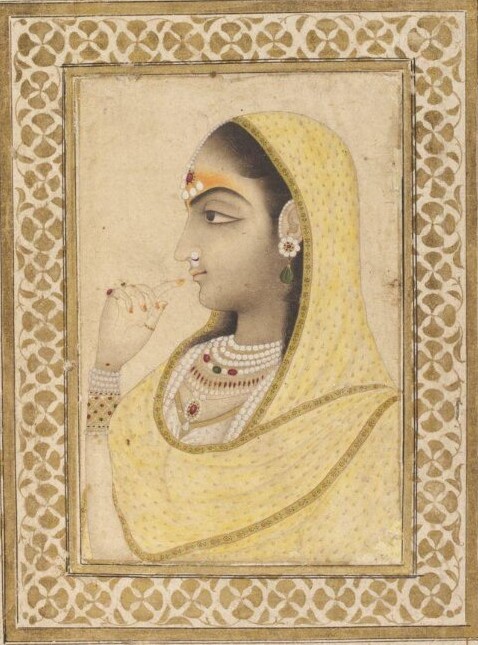

Here’s the ‘Jodha Bai,’ the princess of Jodhpur in an imperial Mughal harem. Not Akbar’s wife, but his son’s. She was never known as Jodha Bai during her lifetime, but by her given name, Jagat Gosini. When she died, Jahangir gave her the title of Bilqis Makani.

Emperor Jahangir, her husband, was born of Maryam, a Hindu princess. And then, Jagat and Jahangir had a son together, Prince Khurram. Who went on to become Emperor Shah Jahan—the man who built the Taj Mahal. Image Source.

Where did the whole Akbar-Jodha Bai fierce romance begin then? A few centuries later. Enter Colonel Tod:

Lieutenant-Colonel James Tod was the author of the voluminous Annals and Antiquities of Rajasthan which deals with the histories of the Rajputs—the people from whom Akbar’s and Jahangir’s Hindu wives were descended.

Tod’s origins were Scottish, and curiously enough, American. His mother was the daughter of a recent emigrant to Rhode Island, and his parents were married in New York. His father then moved to India, to Mirzapur, to grow indigo for the English East India Company, but he was a civilian.

James Tod joined the military branch of the Company as a cadet in 1798, when he was sixteen. In about five years, he was accompanying his mentor as an assistant into regions of Rajasthan and the Maratha Empire. He was promoted to Assistant to the Resident of Lucknow, and became Political Agent himself in 1818. All the while, Tod kept his military handles and promotions of rank.

Colonel Tod, in Rajasthan, in his own ‘royal’ procession—the elephant he’s riding upon, the accompanying Indian army, the British soldiers, and the palanquin carried by foot soldiers. With the Company gaining authority in India, and Indian kings in a decline, the Company men assumed all the royal trappings. Image Source.

It was when he reached that latter, and most powerful position of Political Agent–a liaison between the Company and the kings they had subjugated–that rumors began to circulate of Tod’s empathy with the people of Rajasthan. They called it ‘going native’ then.

In 1822, in disgust, Tod resigned his post and went back to England—for the first time since he had come to India; it had now been twenty-five years.

Out of a personal interest, Tod had conducted vast geographical surveys of northwestern India, and, in performing his various duties, he had learned to speak several Indian languages, and to read and write some of them with a Jain Guru, Yati Gyanachandra.

At home in England, Tod put together his Annals and Antiquities of Rajasthan, based on bardic lore, investigations into existing documents, and conversations he had had during his long stay in India.

Tod’s Annals are the very first attempt to make a cohesive sense of the scattered kingdoms of historical Rajasthan, but the accuracy of his sources is doubtful at best. Even as his books were being published, critics pointed out several flaws.

However, it’s still, even today, a valuable contribution to the history of the region, filled with oral traditions and the beliefs of the people he had conversations with.

What exactly does Tod say about Jodha in the Annals?

Interestingly enough, Tod does not make that vital mistake of identifying Jodha as Emperor Akbar’s wife.

However, he does make another mistake, and being the first person to commit this error—other historians misunderstood him, or did not read his words carefully enough, and proliferated the Jodha-Akbar myth.

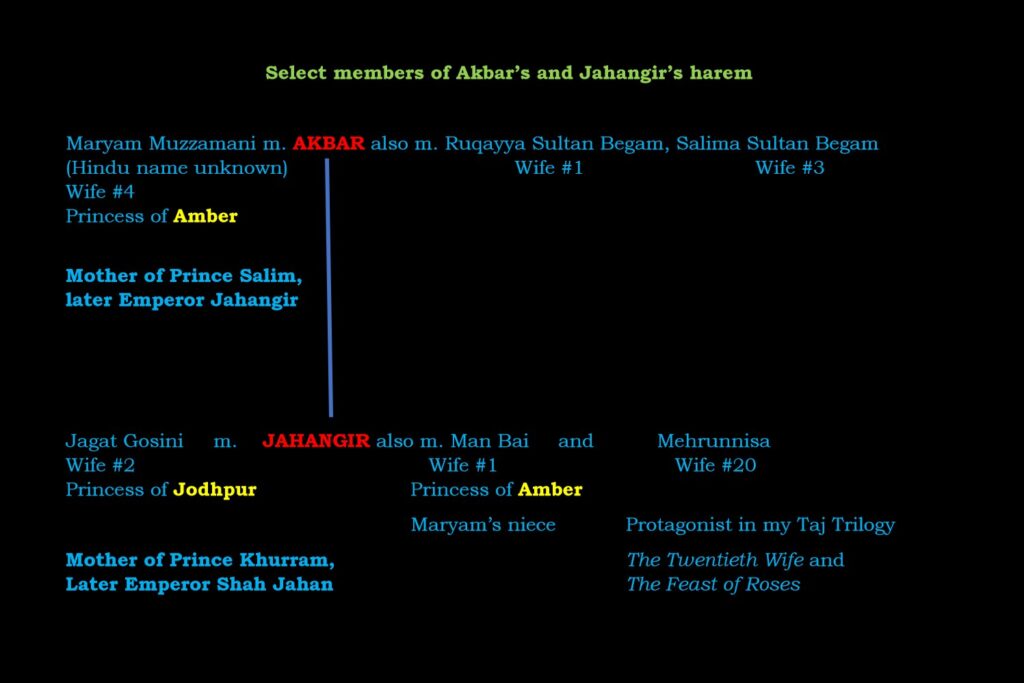

To be clear first, I put together a restricted family tree from within Akbar’s and Jahangir’s harems.

Important things to note: Emperor Akbar married a princess of Amber—Maryam—who was Prince Salim/Emperor Jahangir’s mother. Jahangir married a princess of Jodhpur, Jagat Gosini, who was mother of Prince Khurram/Emperor Shah Jahan.

Jahangir also married his first cousin, Man Bai, princess of Amber, and of course Mehrunnisa, my Twentieth Wife.

So, if you look at the family tree above, you’ll note that the potential Jodha Bai—the princess of Jodhpur—was not Akbar’s wife, but instead his son’s, Emperor Jahangir (and again, she was not referred to as Jodha Bai).

Back to Tod now, and the Jodha mistake in his Annals:

The first (and lasting) mistake Colonel Tod makes in his history of Rajasthan is that he puts a Jodha Bai in Maryam Muzzamani’s tomb at Sikandara (which we’re going to visit).

BUT. And this is a big but. He correctly identifies this Jodha—this princess of Jodhpur—as Jahangir’s wife, and the future emperor Shah Jahan’s mother. Tod does not say that she is Akbar’s wife, but he puts her in Akbar’s wife’s tomb.

Let’s investigate first if the tomb near Akbar’s tomb is that of his wife, or his daughter-in-law:

Is Maryam, Akbar’s wife buried in this tomb? Maryam Muzzamani died in May of 1623, by which time, her son, Emperor Jahangir had ruled over the Mughal Empire for eighteen years. He notes her passing in his autobiography/diary, the Tuzuk-i-Jahangiri.

And then, quite naturally, he buries his mother near his father. The tomb has always been known as Maryam’s tomb, and Maryam was, without a doubt (again, referring to the Tuzuk-i-Jahangiri) Jahangir’s mother.

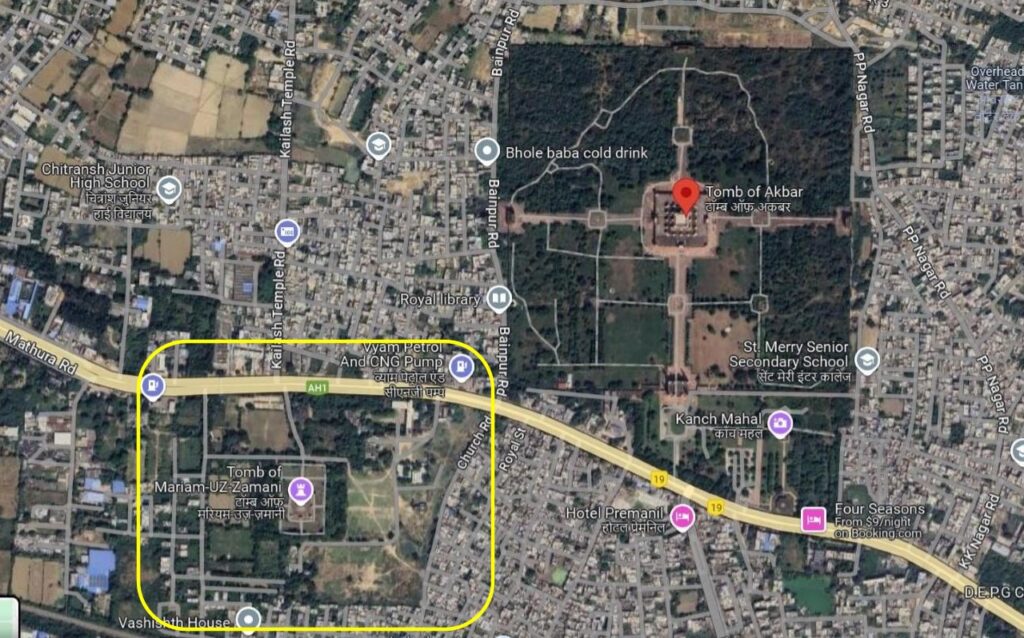

In fact, the tomb is so close, that there’s an early theory—which I’m inclined to believe–that Maryam’s tomb was actually within the larger compound wall surrounding Akbar’s tomb.

Akbar’s tomb is on the top; his wife, Maryam’s, is across the highway, on the bottom left, highlighted in yellow. Image Source: Google Maps

The two tombs are divided today by the modern Delhi-Agra National Highway, which, I think, cuts across the walled area surrounding both tombs. The modern highway does follow, more or less, the old Mughal highway (see the kos minars in Part 1) but not exactly at this point.

So, it’s Jahangir’s mother, and not his wife, Jagat Gosini, who is buried in Maryam’s tomb.

Tod again, and his numerous, bewildering, Jodha references:

Maryam’s tomb at Sikandara comes up—either directly in the text or in footnotes—several times in Colonel Tod’s Annals and Antiquities of Rajasthan. Each time, Tod invariably identifies its occupant wrongly, as Jodha Bai, and as the Jodha Bai who is married to Emperor Jahangir, not Emperor Akbar.

There are other, several, baffling mentions of Khurram, Emperor Shah Jahan (who was the son of Jahangir and Jagat Gosini, princess of Jodhpur) as being the son of a princess of ‘Amber.’ That is incorrect, and then in other places, Tod correctly identifies Khurram as the son of a princess of Jodhpur.

As I said, all very confusing.

What of the other historians: Heinrich Blochmann?

Some fifty years after Tod’s Annals, a German scholar translated the Persian manuscript of Abul Fazl’s Ain-i-Akbari.

The Ain is the third volume of Fazl’s biography of Emperor Akbar, the Akbarnama. And, Blochmann has done a first and definitive job of providing access to it to the world. He too, made one Jodha mistake.

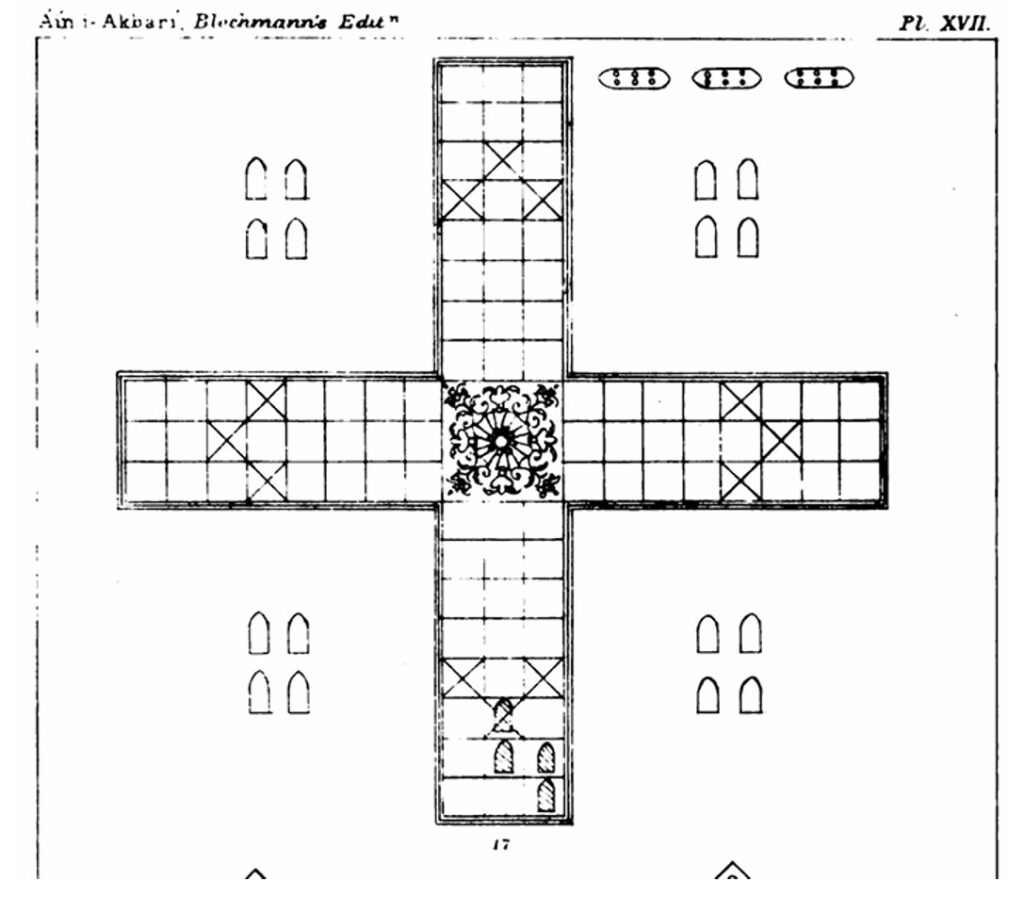

A sketch of the game of chaupar from Fazl’s and Blochmann’s Ain. And, the second picture is Emperor Akbar’s fort-palace at Fatehpur Sikri, where the game board is embedded into the courtyard (see the lighter stones marking the board around the bench in the center).

Fazl gives us every rule for the game in the Ain, how to play, how many players, how the board is laid out, etc. And from this courtyard in Fatehpur Sikri, we know that Emperor Akbar did not confine his game to merely a board, but used this gigantic design in one of his courtyards—and used live pieces on the board, slaves and servants. It was good to be king!

Fazl’s Ain is a marvel of a document—in the first two volumes of the Akbarnama, he tells us Akbar’s history. In this, the Ain, and the third volume, he describes every aspect of life in the Mughal age—army, encampments, lighting, smelting of sliver and gold, the imperial stables, and, yes, the games people played. Image Sources: First image is from The Ain-i-Akbari by Abul Fazl Allami, translator, H. Blochmann. Second image is mine.

In accounting for Emperor Akbar’s wives—this is Blochmann, not Fazl speaking in the translation—he names a Jodha Bai, a princess of Jodhpur. Blochmann then goes on to also identify this Jodha as Emperor Jahangir’s mother. And, he says that she had the title of Maryam Muzzamani.

So here, for the first time, is the other theory about Jodha—that she was the Hindu princess who became Maryam Muzzamani.

Again, that’s not accurate.

Most telling of all, in counting the other wives, Blochmann provides a provenance for his claims—they were mentioned in this, or the other, history from the Mughal period.

For this Jodha, Blochmann says, “Her name is not mentioned by any [Mughal] historian.”

Blochmann corrects himself, almost immediately:

Even before this translation of the Ain went to press—presumably after the type was set, and so changes could not be made in the main text—Blochmann corrects his error in Additional Notes appended to the main text.

Here, he says, he was mistaken about Jodha Bai being Akbar’s wife and Jahangir’s mother. In fact, Jodha—the princess of Jodhpur—was instead Jahangir’s wife. (This, of course, is correct.)

Then, Blochmann correctly asserts that the lady known as Maryam Muzzamani, who was Jahangir’s mother, was the daughter of Raja Bihari Mal of Amber, and so, an Amber princess. (See Part 2 of this blog post for Maryam’s history.)

One more historian who added to the looong Jodha-Akbar myth:

Henry Beveridge is responsible for what I think of as the most authoritative translation of Emperor Jahangir’s memoirs, the Tuzuk-i-Jahangiri. He also translated the first two volumes of the Akbarnama. (The third volume, the Ain-i-Akbari, was translated by Blochmann, above).

His wife, Annette Beveridge, was also a Persian scholar, and translated Emperor Babur’s memoirs, the Baburnama, and Emperor Humayun’s biography, the Humayunama.

I couldn’t find a photo of Henry, but this is his wife, Annette Beveridge, who ran a school for young women in India. And, I suppose in her free time (!) translated both the Baburnama (Emperor Babur’s diary) and the Humayunama (Emperor Humayun’s biography) from Turki and Persian. Image Source.

So, you see, the Beveridges came with extremely impressive credentials.

Some ten years after Blochmann had published his Ain, Henry Beveridge wrote an essay about Emperor Jahangir’s mother.

It’s a little bit all over the place, but he first comes to the conclusion that yes, Jahangir’s mother was Jodha Bai, because there were two Jodhpur princesses married into the royal family—one married to Akbar (and begat Jahangir) and the other married to Jahangir.

And then, to add to the roil, Beveridge suggests that Jahangir’s mother/Maryam Muzzamani could not have been a Hindu after all (and discards his initial Jodhpur princess theory). He posits that instead his mother was Akbar’s third wife, his half-first cousin, Salima Sultan Begam. (I presented this third marriage extensively in Part 1.)

Beveridge wrote this essay a good thirty years before his translation of Emperor Jahangir’s memoirs. If he had studied his own translation of the Tuzuk, he would have realized that Jahangir mentions Salima Sultan Begam’s death in 1611.

Two years later, in 1613, Jahangir notes going to his ‘mother’s house,’ for a ceremony on his birthday.

So, Salima could not have been Maryam, and, could not have been Jahangir’s mother.

Have we established that Jodha did not exist?

So, here’s the chronology of historical errors in brief.

First, no Mughal histories mention a Jodha Bai as Akbar’s wife.

Second, Tod put the wrong woman in Maryam Muzzamani’s tomb. (He said Maryam’s daughter-in-law–mistakenly calling her Jodha Bai–was buried there.)

Next, Blochmann came right out to name Jodha as Akbar’s wife and Jahangir’s mother in the main text of his Ain. But, before it went to press, he corrected his mistake; unfortunately, that correction lies buried in the Additional Notes at the back of the main text.

Then, Henry Beveridge (early on in his career, before he had translated Jahangir’s memoirs) asserted that both Jodha, and then Salima, were possibly Jahangir’s mother.,

Other writers picked up on this, are ran with it. . .and the Jodha-Akbar myth was born.

Now, let’s go to the tomb of the wife who did exist:

It was near lunch by the time we arrived at Sikandara, on our way into Agra. Curiously enough, we couldn’t easily identify a hotel or a restaurant along the road that was speckled with villages and small towns. Nothing but street food stalls.

We stopped at something that looked promising, a catering college. The young man at the desk said they didn’t have a restaurant, but told me where I could find one. We went there—a real Mughlai restaurant, to start our Mughal visitings, and ate flaky butter naans fresh from a tandoor oven, and delicious curries cooked in the Mughal style.

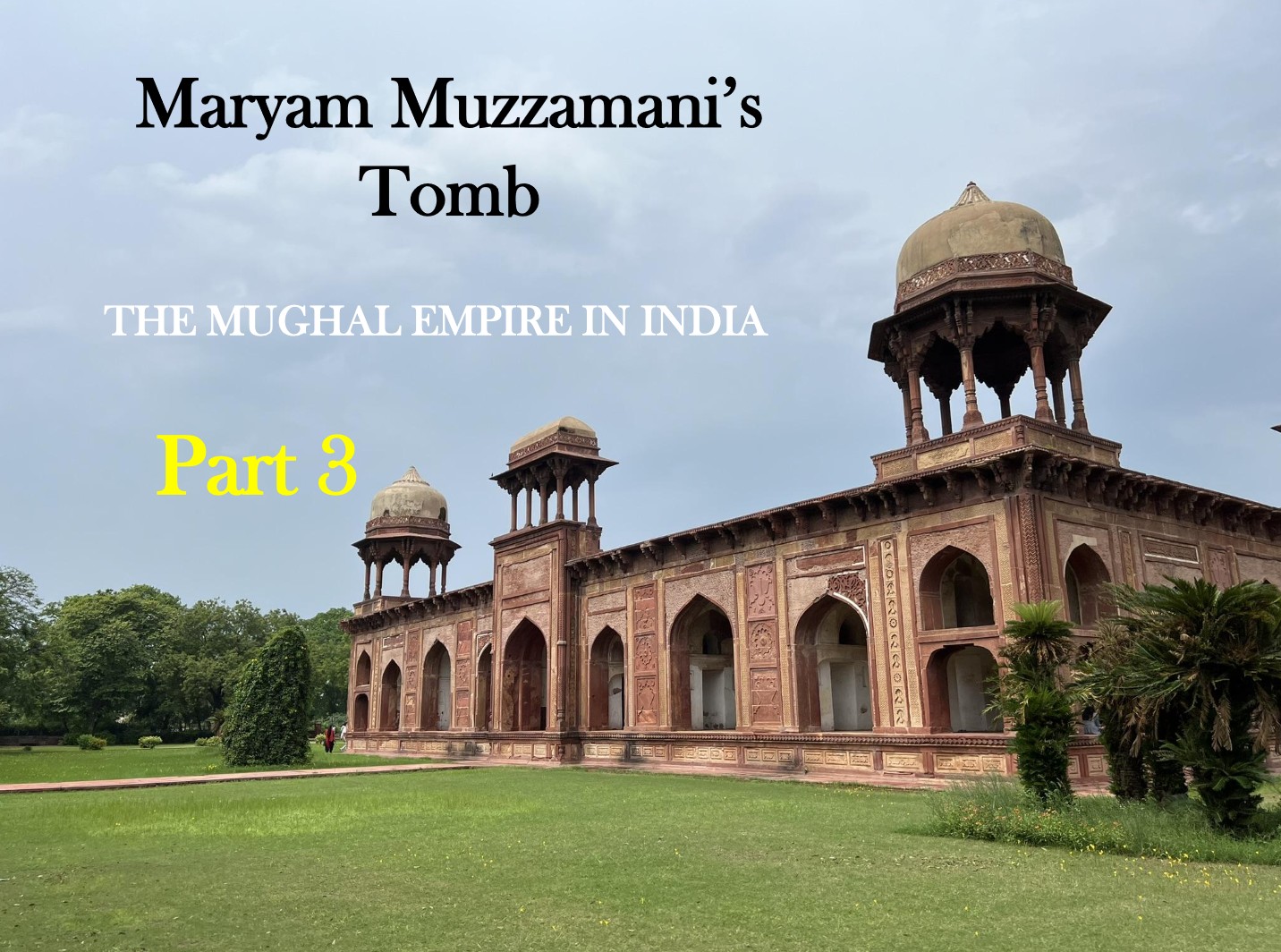

Maryam Muzzamani’s tomb at Sikandara. View from the entry gate.

After lunch, we went to visit Emperor Akbar’s tomb (on a future blog post) and then came across the highway in search of Maryam’s tomb. It wasn’t easy to find, despite the GPS, and we took a couple of wrong turns before we saw the small sign on the highway leading to the tomb.

Emperor Akbar’s tomb—at least, the spectacular red sandstone and marble gateway—is right up against the highway. Maryam’s tomb is tucked inside a side road, not easily visible.

The (somewhat) origins of the tomb?

As I mentioned, there’s one theory that Maryam’s tomb was part of the larger complex of Emperor Akbar’s tomb, given its proximity to the latter structure. The modern highway splits the two—and does follow the old Mughal highway for the most part—so, it’s possible that this section of the modern highway strays from the path of the older one and cuts through the boundaries of Emperor Akbar’s tomb.

If that’s a correct notion, then another theory belies it.

There are several mentions that Maryam’s tomb was originally a baradari, typically a garden pavilion, built a good century before. In other words, the structure stood already, and Emperor Jahangir repurposed it for his mother’s resting place.

The baradari was said to have been built by the then-reigning Sultan of Delhi, Sikandar Lodi. (Emperor Babur, who established the Mughal Empire in 1526, fought and defeated Sikandar’s son, Ibrahim Khan Lodi in the First Battle of Panipat).

The town of Sikandara where both Emperor Akbar and Maryam are buried is named for this Sultan Sikandar Lodi. It’s likely then to have been his headquarters before the Mughals came to India, and the Yamuna River does, in its meandering course, run close by; a water source was essential to any capital city.

Sikandar’s baradari was not a garden pavilion though, but instead a palace of sorts. As evidence, writers point to the presence of forty ‘rooms,’ in the main building.

One of the east-west corridors of the tomb—you can see all the way through. It’s just possible to create a ‘room’ from each of the spaces between the archways, I guess, because several north-south corridors also cuts their way through.

There aren’t really forty rooms as such, just a few corridors that lead from the main entrance (northward) all the way to the south, and a few corridors from east to west.

The so-called Christian queen hosts a church society:

Emperor Akbar has a spectacular resting place, designed initially by him, and after his death, his son completed the structures. Compared to Akbar’s tomb, Maryam’s is almost insignificant—at least, it is today. It’s possible that over the years, people forgot who she was, that successive governments in the area took care of Akbar’s mausoleum, but paid little heed to hers, allowing it to decay.

Inside one of the archways. Like most Mughal tombs and pavilions, the tomb is exactly alike—archways and decorations—on all four sides.

Maryam Muzzamani’s name translates into ‘Mary of the Universe,’ and later travelers (centuries later) mistook her for one of Emperor Akbar’s Christian wives, either Armenian or Portuguese. (Akbar had no Christian wives). (See Part 2 for more on this.)

Sometime in the early 19th Century, the British in India gave the tomb to the Church Missionary Society, and after a famine, they used it to house three-hundred and fifty orphan boys. A gong was suspended in one of the arches to summon the boys to their meals. When not at study, they played in the space outside (it was hardly a garden).

One traveler, visiting the orphanage and the printing press attached to it (the orphans ran the press), and falling for the common mistake of Maryam/Mary/Christian wife, thought it only appropriate that her tomb now hosted Christian children in their studies and their work.

Much later, in the late 19th Century, another visitor wrote that the British government of India had blown up many of the surrounding walls and the gateway leading into the tomb. . .either for mining exercises (!) or because it had become a hub for thieves and robbers. There’s no word on when the Anglican church in Sikandara gave up the premises, or why they did.

Despite the destruction, Maryam’s tomb has a serene beauty today:

As with all Mughal tombs and baradaris or pavilions, the form of the outside space is a charbagh—literally, four gardens. A green space always surrounded either the pavilion or the tomb and it was cut into four quadrants by red sandstone water channels—the channels ran in the middle of the four walkways that intersected in the middle.

At Akbar’s tomb, and here, at Maryam’s tomb, and in other gardens, the main structure stands in the middle of this intersection of the pathways. The Taj Mahal is the only exception—there, to make use of the view over the Yamuna River, the mausoleum is at the waterfront, and in the center is a square pool.

Looking down the north-south walkway, with the tomb at the intersection of the (main) walkways. This path is certainly new, not original—in one of the 19th Century travelers’ reports, the pavements had also been shattered by the mining explosions, and the tomb, inside, was filled with rubble.

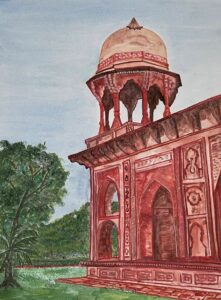

Step a little closer, and you can see the details of the front of the building—which is exactly alike in the four sides of the square structure, they mirror each other. It’s a sort of trompe d’eoil that the Mughals employed in all their architecture, so that you wouldn’t know which side of the building you were facing. And, it’s very effective in giving a uniformity to the style and also allowing the visitor to appreciate details that they may have missed on one side or the other.

The iwan—the main entrance, with its oblong chattri over the archway. Only, this lofty iwan feature is also replicated on all four sides. But, since we just came through the entry gate toward this iwan, I think we can safely say that this is the main entrance!

In the center is the iwan, the entrance into the mausoleum, and it projects outward from the building in a simple, large arch with a pointed top. On either side are six smaller arches, and the quoins of the structure end in a double arch—the top arch is a mezzanine floor.

Legend has it that when Sultan Sikandar Lodi built this, originally as a baradari—a pavilion palace of sorts—it was a flat-roofed building. Emperor Jahangir, reusing it to house his mother’s remains, added all the decorations and the pavilions on the rooftop.

On the roof edges, again symmetrically, are four octagonal domed chattris; a chattri is literally an umbrella, so that shape then for the dome. And in the center, over the four entrance arches to the tomb are four oblong chattris.

A view of the northwest chattri over the quoin of the tomb. Here, you can see the double-arched corner also, with its mezzanine floor.

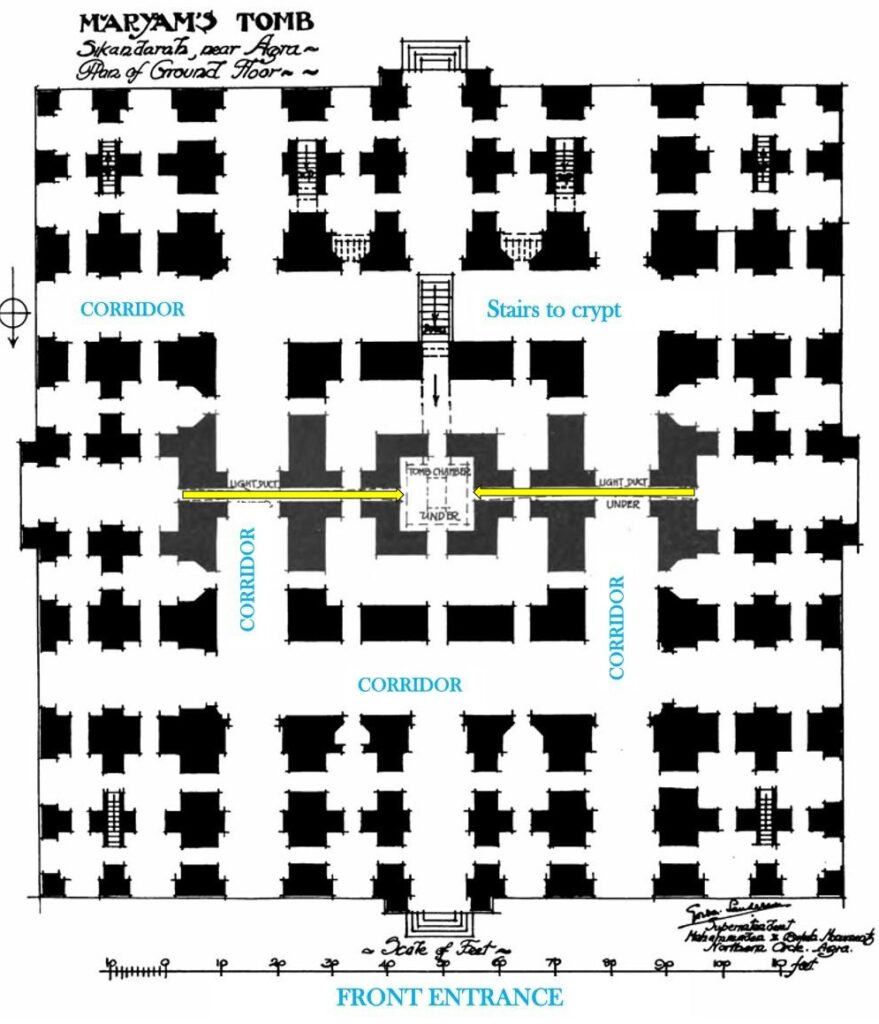

The plan of the tomb:

The tomb is a 150 foot square, with one main corridor running north-south, and two others parallel to the main one. And, two corridors running east-west, intersecting the three north-south corridors. (I tried counting the ‘forty’ rooms, of Sikandar’s baradari, made by all these intersections, and the most I can come up with, I think, is about thirty-three.)

The main iwan leads to the center. And in that square, in the center, is the crypt in an underground chamber below.

If you were to walk straight through the front entrance, all the way to the back, there’s a balcony over the stairs leading down (on this south side) to the crypt.

The plan of Maryam Muzzamani’s tomb at Sikandara. The structure is very simple, again indicative of Mughal love of symmetry and straight lines. I highlighted, in yellow, the original light shafts underground, that lit up the underground crypt chamber—the shafts have been blocked up now. Image Source: Archeological Survey of India, 1914.

The four corridors divide the space into nine parts—at the corners the parts are square, with a set of stairs that lead up to the mezzanine floor, which is nothing more than a room above. The center, again, is square in a series of little chambers. The side partitions are rectangular. It’s a bit of a maze when you are in there!

Here lies Emperor Akbar’s wife, the most beloved:

There’s only one way to access the stairs leading to the underground chamber that holds the sarcophagus of Maryam Muzzamani, Emperor Akbar’s wife. If you walked straight through from the north entrance, you’d be blocked by the baluster that hangs over the stairs, so that no one falls over. It also, effectively blocks you from accessing the stairs from that direction.

So, we walked around into an adjacent corridor and came in from the east.

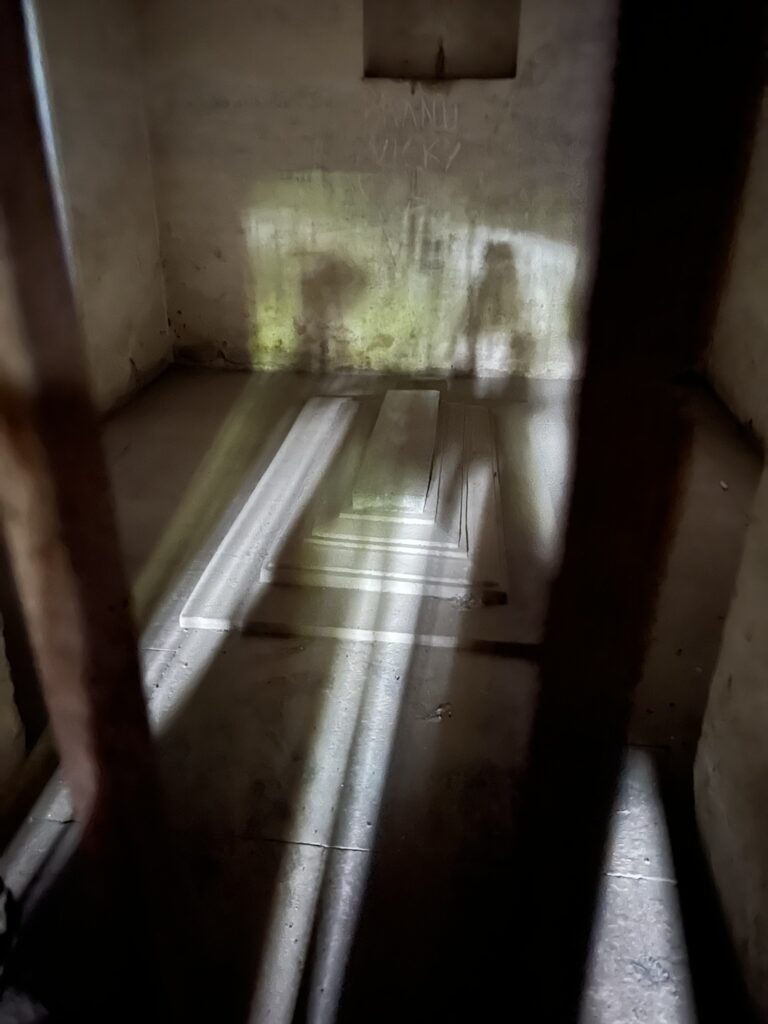

The southern access to the stairs leading to Maryam’s crypt, with the balcony railing above. And, the sarcophagus. Image Sources: First picture, Google Earth; other two are mine.

In the plan above, there are two marked ‘light ducts’ (horizontally, and highlighted with yellow) that lead into the tomb chamber underground, presumably to light it up.

But today, the tomb lies in relative darkness, with the light ducts (from east and west) bricked up, and the only light is from behind, from the south. Doesn’t lead to good photographs—I tried two, and these are the results!

The crypt is simple again, plain white marble, with no engraving on it that I could discern.

There are supposed to be three sarcophagi in the building. One, where Maryam is actually buried, in this underground chamber. Another, in that center square on the ground floor (we didn’t see it, couldn’t find it). And yet another on the roof, open to the sky. There’s no access to this last one.

The details on the tomb:

The beauty of Maryam’s tomb lies all on the outside. Perhaps there was more carving on the inside at one time, but it’s all gone now, apart from the structure of the domed ceilings inside.

In remodeling what is supposed to be Sikandar Lodi’s baradari, Emperor Jahangir also refaced the walls of the building—built with brick and mortar—with slender panels of red sandstone.

The panels are carved again, very simply.

The Mughals, being Muslim, did not depict living figures. So here, the decorations are in the shape of incense censors, flower pots, and vases.

Detail on the red sandstone panels of Maryam’s tomb.

The external angles (quoins) of the building are also fretted in tiny detail.

The right-angle corner of the mausoleum, with the double-arches of the balconies.

As is the platform that holds up the tomb.

So, was Maryam’s tomb Sultan Sikandar Lodi’s baradari?

Perhaps like the whole Jodha-Akbar story, and Jodha-being-Maryam story, this too, I think, is something that passed into legend, with its origins unknown.

If you hire a guide here, he will tell you that Sikandar Lodi built the baradari in 1495. (Again, the Mughals didn’t come to occupy India until 1526).

But, there are several things against this theory, to my thinking, at least.

One, it’s too close to Emperor Akbar’s tomb, and if this area was indeed a part of the larger complex of Akbar’s resting place, then, it’s logical that Emperor Jahangir would have buried his mother here, next to his father.

Two, this whole reusing an existing (and more than a hundred-year-old) building to house his mother’s remains, just doesn’t fit with Emperor Jahangir’s character. He was a man with an exquisite eye for detail, a fine sense of the appealing, an inbuilt arrogance from his royal birthright, and would have disdained repurposing another structure, when he could build a new one that would keep his name well into posterity.

Also, just about a year before his mother died, his favorite wife, Empress Nur Jahan’s father died, and she had begun building a magnificent tomb for him, across the Yamuna River from the Taj Mahal. (We will go there, for sure, on a future blog post—and I talk of the tomb in the second novel of my trilogy, The Feast of Roses). Since Empress Nur Jahan was building her father’s tomb during this same time period, here are two pictures below, comparing the decorations on the walls of the entrance gateway with Maryam’s tomb.

On the left, the detail on Maryam’s tomb. On the right, very similar ornamentation on Nur Jahan’s father’s tomb at Agra. The main difference between the two, of course, is that one is carved in relief and the other is a marble inlay in red sandstone.

Given how similar the decorations on both tombs are, I’m inclined to think that Emperor Jahangir built this tomb for his mother, Maryam, along the same lines as his wife’s father’s tomb. And, he built it from the ground up.

Another thing: Maryam’s tomb—however it may have changed from neglect over the past centuries—doesn’t really fit the Lodi form of architecture, but is more akin to what is called early Mughal architecture. In other words, during Emperor Jahangir’s rule.

One final thought about this Hindu princess in a Muslim harem:

I’ll make this brief here, and expand on it further when we visit Emperor Akbar’s tomb in Sikandara on a future blog post.

We do not know the Hindu name of the princess of Amber who married Emperor Akbar and gave birth to his son and heir, Emperor Jahangir.

She’s only known by her Muslim name—Maryam Muzzamani. But, was she actually Muslim? Did she convert to Islam when she married Akbar? (Fazl, Akbar’s biographer, does not touch this topic in his Akbarnama.)

Emperor Akbar experimented with ideas and thoughts from both Hinduism and Islam. It’s possible that he was thus influenced by his Hindu wives. He certainly had three Hindu wives, the princesses of Amber, Bikaner and Jaisalmer.

It is known that he allowed his wives to practice their religions within the walls of his harem. That he took part in their homams or havans, which were rituals with the holy fire. That they put the tika, the vermillion mark, on his forehead, and he wore it inside the harem only at first, and later outside.

In the fort at Agra (future blog post) there’s a little altar to a Hindu god embedded in one of the marble walls of a courtyard. Has it survived intact from Mughal times? Or, was it put there by some other conqueror after the Mughals?

Emperor Jahangir, Akbar’s son, also had several Hindu wives, and he permitted them, similarly, to follow their devotions inside the harem. He was born of a Hindu mother, of course, and his son and heir, Emperor Shah Jahan, was also born of a Hindu mother, the princess of Jodhpur.

Whatever freedoms these two emperors gave their wives in adhering to their religion, the sons were brought up Muslim. No Mughal emperor of India could profess a faith other than Islam.

But, perhaps, even that early on, even being the first Hindu and Rajput woman to marry into the imperial Mughal family, Akbar’s wife, Maryam Muzzamani, remained a Hindu.

If you’ve enjoyed reading this post, please share it, so others may read also. Thank you!

Keyword phrases: Is Jodha Akbar story real; Jodha Akbar real story; Mughal Emperor Akbar; Emperor Akbar’s tomb; Akbar the Great; Mughal harem; Mughal Empire in India; where was the Mughal Empire; Akbar’s wife; Indu Sundaresan books; Twentieth Wife; Taj Trilogy.

Primary Sources: Henry Beveridge, trans., The Akbarnama of Abul Fazl, 2 volumes; Heinrich Blochmann, trans., The Ain-i-Akbari by Abul Fazl Allami; Lieutenant-Colonel James Tod, Annals and Antiquities of Rajasthan, 3 volumes; Vincent Arthur Smith, Akbar the Great Mogul, 1542-1605; Pringle Kennedy, A History of the Great Moghuls; Henry Beveridge, trans., and Beni Prasad, The Maathir-ul-umra; George Ranking, trans., Munktakhab-t-Tawarikh by Al-Badaoni; Rima Hooja, A History of Rajasthan; B. DE, trans., The Tabaqat-i-Akbari of Khwaja Nizamuddin Ahmad; William Henry Sleeman, Rambles and Recollections of an Indian Official; Beveridge, Henry, article in Journal of the Asiatic Society of Bengal, Volume LVI; Annette Susannah Beveridge, The Baburnama in English.

On the next blog post—we travel to northwestern France—to read the story, on a 12th Century length of linen, of William, the Duke of Normandy’s conquest of England—The Bayeux Tapestry—An Embroidered Tale—Part 1

Indu —

What a treat it was for me to read this blog. I lived for four years in New Delhi and have written a book on the Taj Mahal (Taj, The Woman and The Wonder) For background, I had to research many tomes as well as visit a number of areas in India. I loved doing all of this — including a research trip back to the subcontinent after I had returned to the States.

To read your words and see your photos of places I knew was trip for me. Not unlike riding a magic carpet to somewhere in the past that I had enjoyed for many years. While reading your blog I was making my own family tree from your words to absorb the names and relationships of people who had become very familiar and fascinating to me.

I thank you for your books and for giving me this opportunity to return to Mughal India.

Thank you for this comment, Sandra. I’m glad to hear that you, who have also researched the Mughals extensively, enjoyed this post on Akbar’s wives. And yes, so much of Delhi is steeped in history, that you cannot live there without marveling when you visit those splendid monuments. I still walk around in blissful wonder when I visit Delhi.