Which Thomas Hardy? Search for ‘Thomas Hardy’ and—apart from our book-related Hardy—two other very interesting results also show up. One is about the trial of a Thomas Hardy for high treason, and the other about an altarpiece—a reredos—discovered behind the wooden altar in All Saints Church, Windsor, and attributed to a Thomas Hardy.

Thomas Hardy’s reredos in All Saints Church in Windsor.

Thomas Hardy’s reredos in All Saints Church in Windsor.

No prizes for guessing which one relates to our novelist. It’s doubtful he could have committed high treason, no less, and no one’s mentioned it before. But, his end-of-novel biographies also possibly do not contain that other little fact, that yes, Hardy was indeed an architect and a draughtsman before he made his name as a writer.

The other Thomas Hardy, the treasonous one, was a shoemaker, a humble artisan. He was tried because he protested being either unable to vote for his parliamentary representative since only a small male electorate was eligible to vote, or that the representative was more or less appointed by the landed, the rich, and so represented them and not the common man. So, both news snippets about the both Hardys are actually honorable.

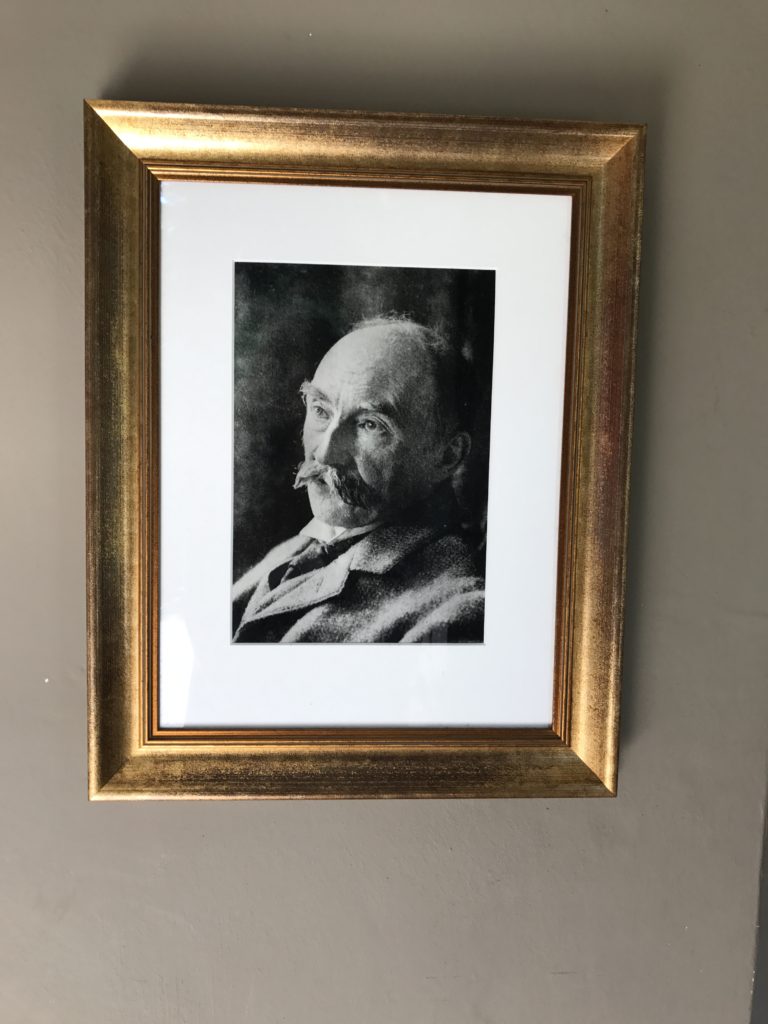

The other Thomas Hardy. Source.

The House that Tom didn’t build: Thomas Hardy was born in June 1840, in Higher Bockhampton, in the cottage his great-grandfather built, cutting out the land for it from the heath. John Hardy built the cottage for his son, Thomas, our Hardy’s grandfather, who then had an oldest son, also Thomas Hardy, who then begat our Thomas Hardy. It’s all a bit confusing, the slew of Thomas Hardys, but it’s safe to say that several Thomas Hardys lived in that cottage. John Hardy, the great-grandfather, was a builder, then. His son, Hardy’s grandfather, also owned a brickworks and supplied the material for local lords and landholders—Hardy’s father (and his brother Henry consequently) continued in the family business.

Thomas Hardy’s birthplace in Higher Bockhampton. Source: Chris Downer

When Hardy was sixteen, he was apprenticed to a local architect. It was a calculated move; Thomas Hardy père was looking ahead at the architect son drawing up plans that would be executed by the builder son, Henry Hardy. All in the family. And so it turned out, at least, when Hardy built Max Gate…but more on that anon.

The first steps out of Higher Bockhampton: Hardy first went to school at Higher Bockhampton when he was eight; until then he was educated at home, mostly under the guidance of his mother, Jemima Hardy. He then moved to another school in Dorchester—which necessitated a three mile walk each way. There was a world of difference between his home and the bustling town where his school was situated, because in those days, progress came no further than the outskirts of Dorchester. And so, he lived in these two worlds for almost ten years, even after he started working for a local architect at Dorchester at sixteen. And during that walk each day—to school, to work—he absorbed impressions of the countryside, the people, the nudging of modernity which receded once he came back to Higher Bockhampton, and stored it all away for his future writing. At work, Hardy graduated from copying to working on restoring buildings and churches.

Thomas Hardy’s photo at Max Gate.

Into the Madding Crowd: When he was twenty-one, Hardy moved to London to find work. If Dorchester had been a big bustle compared to his sleepy hamlet of Higher Bockhampton, London smacked him in the face, with its fast pace and crowded streets. Life was all around, stinking, unseemly, unwashed. Hardy did well in this field chosen for him by his parents, even winning a few architectural competitions. But, this life, this so called progressive life of ambition and competition, was not for him. Two years later, he still worked at the firm, but at home, by night, he read and began writing poetry that no one published. He dabbled with the idea of writing for the newspapers, as an art critic, but that too fell on the wayside. A few years later, in 1867, he returned to Dorchester a broken man—his faith weakened—to work at his old firm, and to write. It was now—living in his childhood cottage at Higher Bockhampton—that Hardy began to write his novels. Desperate Remedies, Under the Greenwood Tree, and arguably, his most famous novel, Far from the Madding Crowd, were written here, during this time when he had come back home, disillusioned with his work as an architect, searching for his place in the world as a writer.

The entrance to Max Gate.

He hadn’t fitted into London, or taken interest in the doings of the upper class there, and when he came back home, he found that the five years away had made him…an outsider. The spit and polish that he had acquired in London, made Higher Bockhampton and its inhabitants more backward, more firmly ensconced in that past that Hardy had left behind. But, it also gave him this unique viewpoint for his future writings. He was no longer as vested in the hamlet’s culture as he had once been, and he was just far enough away now to see it with the clarity of a novelist’s gaze.

Tryphena Sparks

Tryphena Sparks

The First Love? Or not? Or what? Hardy now fell in love with his cousin, Tryphena Sparks, his mother’s sister’s daughter. He had had other love affairs before this, and perhaps because he was a thinking, thoughtful man, they had all left their mark on him in one way or another. This was different. It was hot and heavy for at least two years, and then it broke off. Tryphena died in 1890; by then, Hardy had been married to his first wife, Emma, for sixteen years—but, in 1890, his marriage was coming apart. Upon hearing of Tryphena’s death (Hardy called her ‘Phena’), he wrote a poem titled ‘Thoughts of Phena.’

Not a line of her writing have I,

Not a thread of her hair,

No mark of her late time as dame in her dwelling, whereby

I may picture her there;

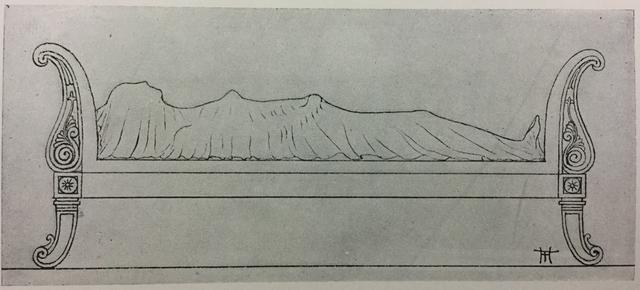

Hardy also speaks of Phena’s dreams ‘upbrimming with light’ and of the laughter of her eyes. It’s an unabashed love poem. And then, somewhat morbidly, he draws her in death, her body lying shrouded on a scroll arm sofa which came from his dining/drawing room. Both the sofa and Hardy’s sketch are displayed in the dining room at Max Gate today.

Hardy’s sketch of Tryphena, with his initials, bottom right.

The poem, and the sketch, are the only indications of the depth of Hardy’s feelings for the woman who was…what? A true love? His only love? The love that got away? We’ll never know, because he held his secrets close. In his later years, Hardy did write his own ‘biography,’ in the third person, which was published after his death. But, his life in it is a clean, spanking, sanitized version of what it possibly was. As with most writers, it is in his books and his poetry (more personal) that there are glimpses of Hardy the man behind the novelist. The man who, when his marriage was frayed, looked back wistfully at what might have been…

It was now, during this interim period between fully leaving architecture and blossoming into a published author that Hardy worked on designing and executing the altar at All Saints’ Church in Windsor. The reason Hardy’s reredos is more recently in the news is that no one had known that there was this proof of his architectural background, other than Max Gate, of course. In the 1970s his sketch for the reredos was discovered behind the organ at All Saints. It was then displayed in the church. The altarpiece itself was a wooden, carved panel done sometime in the 1920s or 1930s. A couple of years ago, a member of the congregation, looking for the foundation stone, shone his flashlight behind the wooden panel of the altar and saw pillars and a design that looked like the Hardy design hanging at the back of the church. The church raised the money to carefully remove the wooden panels and restore Hardy’s reredos—this, I think, was done sometime earlier this year. Here’s another look at the reredos.

Thomas Hardy’s reredos in All Saints Church in Windsor.

Thomas Hardy’s reredos in All Saints Church in Windsor.

Hardy sets down roots in Dorchester: Even after the move back home, Hardy spent time in London, especially as he began publishing. He went there on and off, and lived at other places also, until he decided to return to Dorchester. By now, he was married to his first wife Emma (in 1874). In 1883, he bought a plot of land on Wareham road, and drew up the plans for his house. Most of his work as an architect—by virtue of the bosses who had employed him—had focused on church building and restoration. The closest Hardy had come before to designing an actual house was to draw elaborate plans for a townhouse, unrealized in brick and mortar.

Max Gate, possibly photographed soon after Hardy’s death, in the 1930s. Photo’s taken from the gardens; you see the glassed-in conservatory. The windows above are from one of the original rooms in the house, used as Hardy’s first study. Source.

He asked his father and brother to build the house, and, what’s it they say about never employing family? By the end of the construction, with our Tom nitpicking on everything, his father declared that no amount of money would convince him to build another house for his son.

Thomas Hardy drew elaborate plans for his little house, every detail accounted for. When the work began, and the foundations were dug, he discovered three Roman era skeletons on the grounds—so, the land had a far-reaching history. Hardy named the house Max Gate, after Henry Mack, the last toll collector in a nearby toll booth, which was known as Mack’s Gate. Hardy and Emma moved into Max Gate in 1885.

Max Gate, the front. Windows to the right are the drawing room (which leads to the conservatory); to the left the dining room. On top, windows to the right are Hardy’s first study; windows to the left, the master bedroom.

Two up, two down: To begin with, Max Gate was a small house, a ‘two up two down.’ More or less. The front foyer led to the drawing room on the right, the dining room on the left, the stairs to the upper floor were in the foyer to the right, and the short passage to the kitchen ahead to the left. Upstairs, the ‘two up’ were Hardy’s study over the drawing room, the master bedroom over the dining room, and the dressing room in between, over the foyer. Tucked away to the left, next to the master bedroom, and over the kitchen, was a small room, the guest bedroom.

Left, looking up the staircase toward the door to Hardy’s first study (above the drawing room), with the door to the dressing room facing the railings. Right, the main staircase leading to the rooms upstairs.

The servants slept in the attic, above Hardy’s study, and their stairs were directly behind the main staircase in the foyer. These servants’ stairs still exist, but the door leading to them, and the attic space for their bedrooms, was locked up on the day we visited.

The price of fame: When Hardy and Emma first moved into Max Gate, there was only empty ground all around. And the views went all the way across that vast expanse of nothing, right down to the road. When they sat in the dining room at breakfast, at lunch, or entertained friends—passersby looked in at their friendly domesticities.

It became a problem. Hardy was now fairly famous, enough so people came to stare at him from across the fields. He built a red brick wall, guarding his privacy. But, walls can go only this high—we had parked on that road also (there seemed to be no parking lot for Max Gate) and you can easily look over it when you get into a biggish car. In Hardy’s time, it was buses, raised high, seating twenty or thirty tourists, comfortably gawking over the wall at the house, and perhaps Hardy walking in his garden ruminating on a plot point or a character. And, he would hear something like, “ere, ladies and gents, is the ‘ouse of ‘ardy, the novelist!”

Max Gate today, still shady, but nothing like the Austrian pines!

So, Hardy planted a thousand Austrian pines—evergreens—that would shut out those gawkers. He laid out his garden meticulously. A lawn, smooth and green, to the right of the house, a series of hedges that divided the garden into three parts. A kitchen garden, a place to have tea. Over time, those Austrian pines grew and grew and pruned out light and air, shut out prying eyes, of course, but also shut them all in damp and dank and gloom. I bet nothing grew in that kitchen garden.

After Hardy’s death, his second wife, Florence, had them all cut down.

The vegetable garden, beyond, and a little sitting area in the foreground, at Max Gate today. Similar, I think, to how Hardy had originally planned the garden.

Today, thanks to Florence’s ruthless pruning, the garden is a delight. Trees along the perimeter, their shadows casting cool only partway in the garden, enough sun for vegetables to grow and flowers to bloom—the volunteers keep the gardens immaculate, recreating them as they must have been in the early days when Hardy lived at Max Gate.

Florence’s bathroom with the cast iron bathtub.

My kingdom for a bath: Indoor plumbing, something we all take for granted nowadays, didn’t come to Hardy’s home until about 1920—until then, Hardy sat in a hip bath in his bedroom, sponging away the day’s travails, with half a gallon of hot and half a gallon of cold water. That doesn’t seem like much water at all, but I suppose if you have to lug water up a flight of stairs…it’s plenty, at least for the person who’s carrying it. His second wife, Florence, wanted a bathroom, a real bathroom. So, Hardy then carved out a bit of the upper room (his first study) over the drawing room and created one. It still contains the cast iron bathtub that he installed. And, the bathroom became a feature in the house; when visitors came, he took them upstairs and showed them his marvel.

For a Victorian house—without central heating, fireplaces everywhere, drafts sneaking in through window seams, no matter how tightly sealed—Hardy built a drawing room with a massive window facing the front of the house. It’s almost modern, that’s what I thought when I stood in front of it. This could be a window in any, newer, house, where you didn’t have to care about heating.

The drawing room window, left, and the door leading to the conservatory.

At the far end, sometime in 1913, he constructed a conservatory. At Max Gate today, the curators have attempted to recreate Hardy’s furnishings from old photos as much as possible. It’s so well done, it gives you a fly-on-the-wall view. There’s a screen around the armchair by the fireplace, because fires were the main and only source of heat, and fires didn’t heat the whole room, just that little rectangle in front of it. So, Hardy would snuggle down into his armchair, close the screen around him and the fire and read, or write, or drink a glass of wine before going up to bed.

The drawing room, with the screen around the armchair.

There’s a piano on one side of the room, not original but old, just as there must have been when Hardy lived there. One of the curators says that this is one of the few National Trust properties where “you can touch anything!” So the kid sits down at the piano and belts out ‘Für Elise.’ The first few notes sound good…and then not. The piano needs tuning.

Left, the sideboard in the dining room, and right, the desk and typewriter, not original, if I remember correctly, but sort of from Hardy’s time period.

The dining room is also set up much as Hardy must have used it. The table is original, so also the sideboard. I can’t remember now if the desk and typewriter here also belonged to Hardy, but the kid, thrilled at seeing an actual typewriter, bangs out a love letter to me, which I still have. The dining table takes up most of the space in the room, large enough, it is said, for the Hardy dogs and cats to sit on the table and walk around it as the guests ate their dinners!

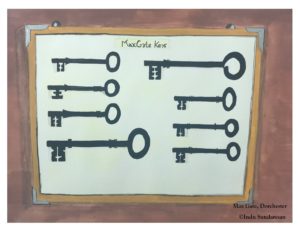

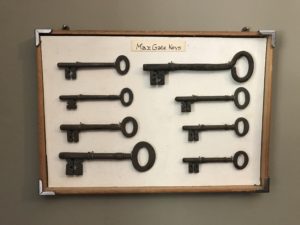

The original Max Gate keys displayed at the house.

If you’ve enjoyed reading this, please consider sharing by emailing a link to the post, and by hitting the social media share buttons below, so others may read also. Thank you!

On the next post—A Space to Write—Hardy’s two wives—the other women in Thomas Hardy’s life—Max Gate: The House that Tom built—Part 2

I’ve been sitting here for hours reading your blog, whose existence I was completely unaware of til this morning….and what a shame that is! I’m a huge fan: I love your historical fictions, absolutely love how you take historical figures and events, and put a ‘script’ to them…a narrative. And reading through your blog, I can relate in every way to how your creation of these scripts and narratives works; visiting historical places, reading of their history, of their people, all the details start to form a story. My favourite is Twentieth Wife; I have read it several times…so happy to find you here, when I went searching for your details so my agent could write to you :))

Braja, thank you so much for these kind words! I love your photo gallery–the colors, that dog in the watering trough with a boy-the-water’s-cold-how-long-do-I-have-to-sit-here expression! I’m looking forward to reading your work, and I hope you come back to read here also.