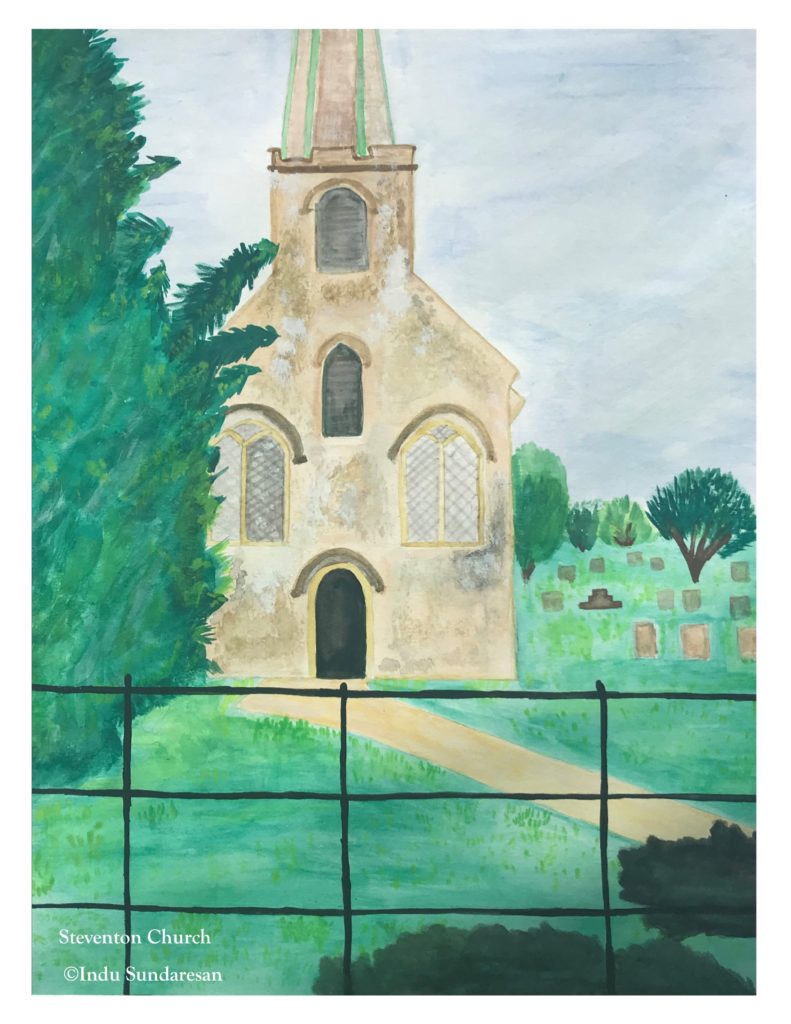

I’m in a churn of delight when I glance at the GPS and see that the Church of St. Nicholas is not more than a half mile away from the turning. Like the best of anticipations, I can’t see the church as we drive along the road, only trees that clot the roadside and arc their branches over, letting little tatters of sunlight through. It’s a slim, country road, a one-laner. Eventually, we hit the end of the road, and the church raises its steeple on the left in a miniscule churchyard. Birds coo and chirp, bees hum in the sunshine; there’s one other car in the parking lot, whose occupants leave almost as soon as we get there.

‘Church Walk;’ the road leading to the Church of St. Nicholas in Steventon.

For all of Jane Austen’s everlasting fame, this place where she lived for the first twenty-five years of her life—Steventon—and the church where she worshipped, are off the celebrity map. Or, at least, on the very fringes of it. For that, I’m grateful, because I came here to commune with the place, to sit happily by myself, to look around, and to imagine what it might have been like when she lived here.

To Steventon we go: Jane’s father, Reverend George Austen, was given his living of the parish of Steventon in 1761 from his cousin’s husband, Thomas May Knight. The Knight son–Thomas Knight–would figure largely in the future in all their lives by adopting one of George’s sons, and Jane’s brother, Edward. And so Austens would hold that living for a great many years–first George (the father), then James (Jane’s oldest brother) and then William (Jane’s nephew; Edward’s son).

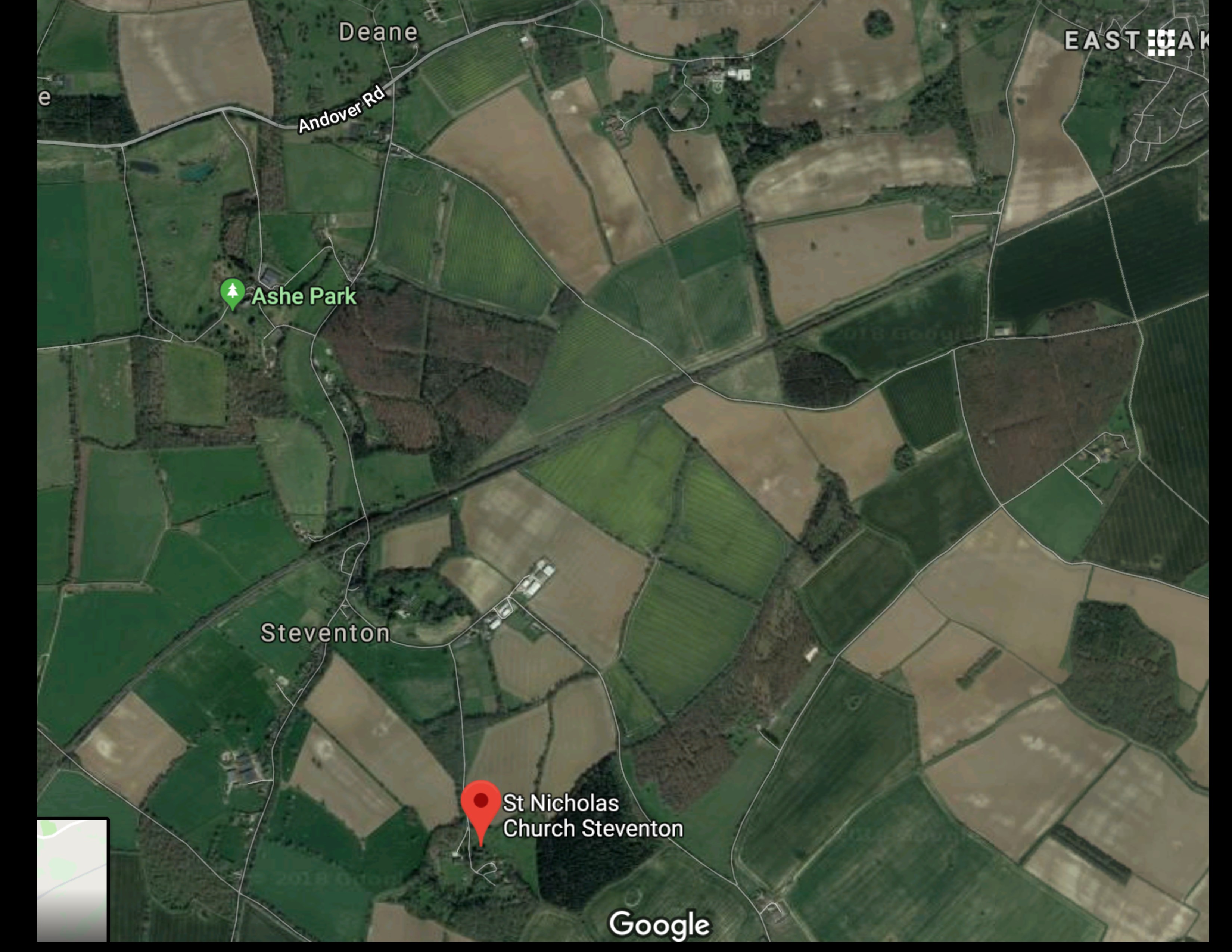

George and Cassandra Austen were married in 1764 and moved to the small parsonage in the neighboring parish of Deane (the then-incumbent being rich enough to rent the manor of Ashe Park and Steventon rectory being uninhabitable) and had their first three sons, James, George, Edward. When Reverend Austen’s stepmother died and released her hold on his paternal property, they had enough money to renovate the house in Steventon and shift there. Eventually, Reverend Austen would also acquire the Deane living, whose reversion had already been bought for him by an uncle.

The Church of St. Nicholas and Steventon, south on the map, and Deane, north. Ashe Park is midway. Source: Google Maps.

The Church of St. Nicholas and Steventon, south on the map, and Deane, north. Ashe Park is midway. Source: Google Maps.

Today, it’s a flat, macadamized road from Deane to Steventon—2 miles and a six-minute drive. But, when George Austen moved his family in 1768, even that short journey was difficult. The road was pitted and rough from wind and storms, and not always repaired immediately or kept in good condition. If anyone wanted to travel, they took their chances. And, if they really wanted to get somewhere, they hired a crew of men to smooth out the path in front. Cassandra Austen was not ‘in strong health’ during this move, possibly, given the four-year gap between Edward and the next son, Henry, she had just had a miscarriage. She lay on a feather bed on top of their possessions on a wagon and thus they traveled to Steventon.

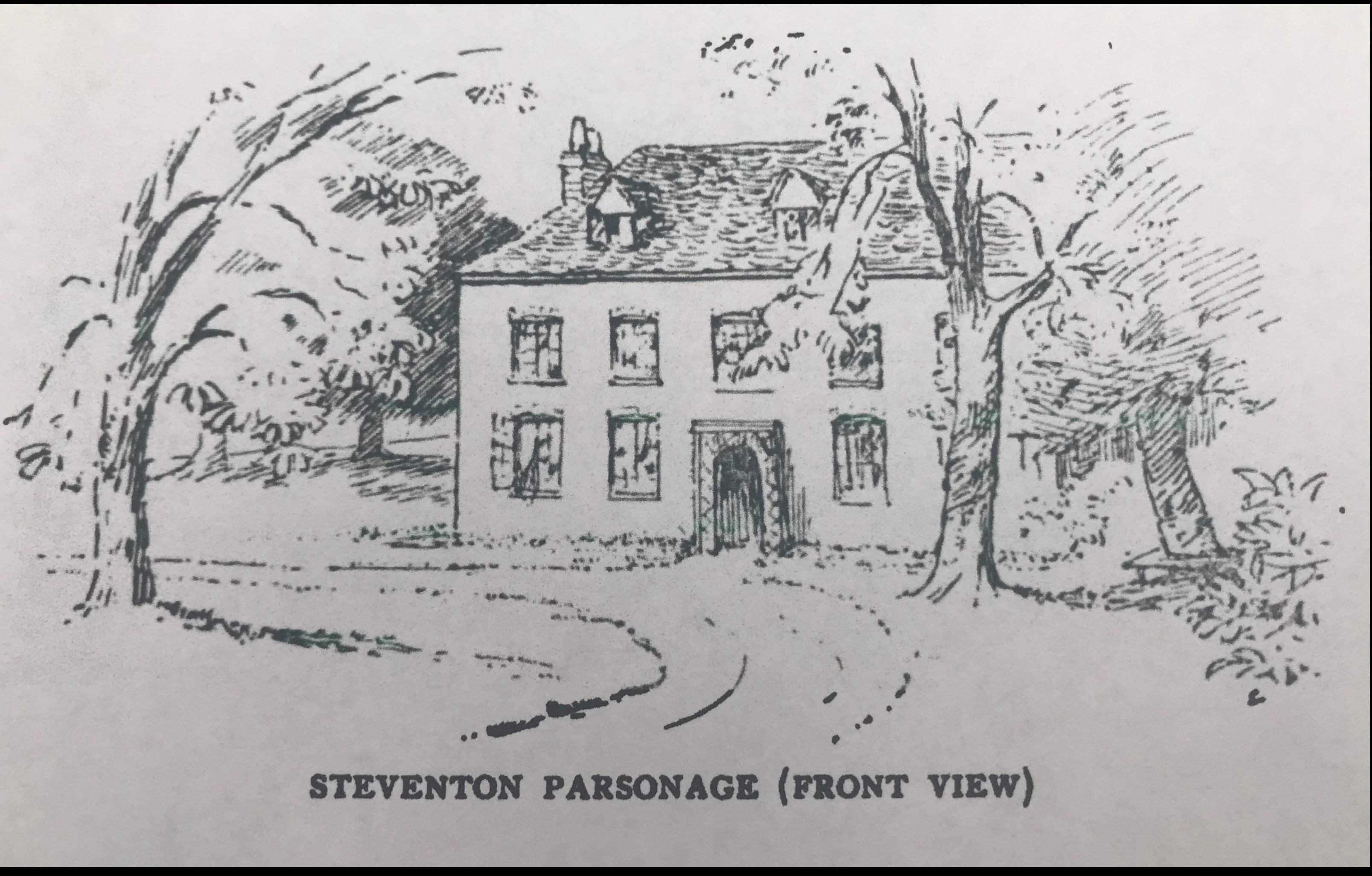

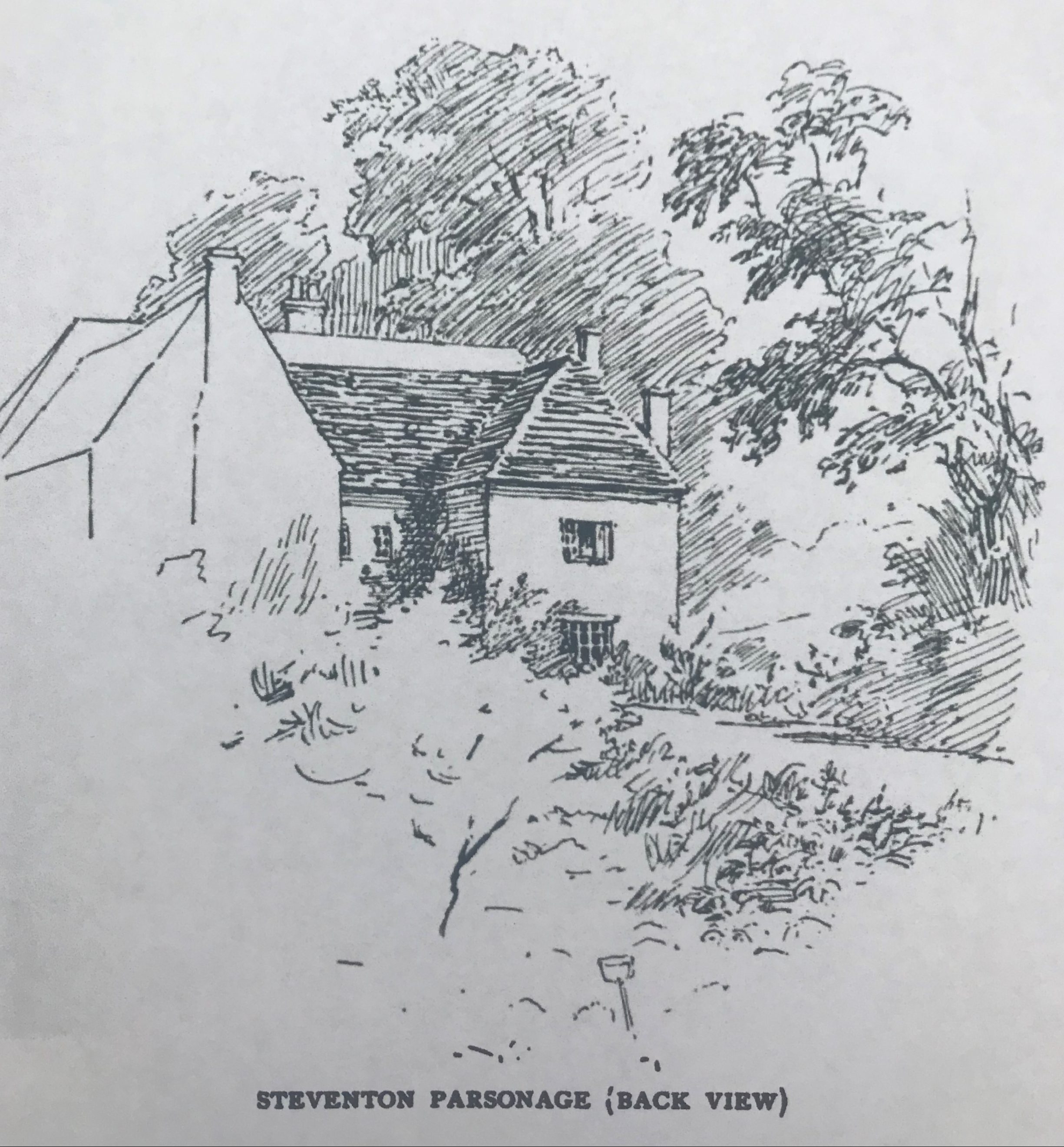

Seven years later, after the births of Jane’s only sister, Cassandra (named for their mother, and born in 1773) and a brother, Francis, Jane was born at the rectory at Steventon in 1775. She was twenty-five before they moved away permanently, and it is here that she wrote her most famous novels, Sense and Sensibility (initially titled ‘Elinor and Marianne’) and Pride and Prejudice (initially titled ‘First Impressions’). Steventon Rectory. The sketch is attributed to Anna Lefroy, Jane’s niece. Source: Jane Austen: Her Homes & Her Friends, by Constance Hill.

Steventon Rectory. The sketch is attributed to Anna Lefroy, Jane’s niece. Source: Jane Austen: Her Homes & Her Friends, by Constance Hill.

The rectory at Steventon was the only home Jane Austen knew for a while, and observing the people in the parish, listening to their stories, watching their mannerisms, gave her fodder for her novels. Deane and Steventon are some fifty-five miles from London, but as country as country can get. George Austen had the care of only 300 parishioners in both villages and the all that farmland around. As insular as this may seem, Jane had plenty of opportunities to imbibe other influences. She visited her brothers’ homes elsewhere, and she was also sent away to school for a bit. Following what must have been the custom of the times, all the eight children spent almost the first two years of their lives in the village in the care of a dry nurse, and only came back to the rectory after they were out of leading strings.

Jane Austen’s formal education was sporadic. She left home when she was seven, in 1783, for a ‘school’ run by a gentlewoman in Oxford, who fled to Southampton with her pupils without informing their parents, and there, they caught typhus which almost killed Jane. Two years later, she went to another (actual) school at Reading. She was eleven when she returned home to stay. At both schools—the first typhus one and the second one at Reading—she accompanied her beloved older sister Cassandra. The two them were almost never apart, unless they were visiting friends or relatives separately. It was a lifelong friendship, at least for Jane—because after she died, Cassandra and her mother lived on.

School was obviously not a successful venture for Jane, and yet, the rigors and horrors of schooling don’t, interestingly enough, make it into her novels. Perhaps because she wasn’t in school long enough, unlike those other famous novelists, the Brontë sisters; think of Charlotte Brontë’s Jane Eyre. (We’ll visit the Brontë home, Haworth Parsonage, on future blog posts, and I’ll talk more then about the Brontë schools.)

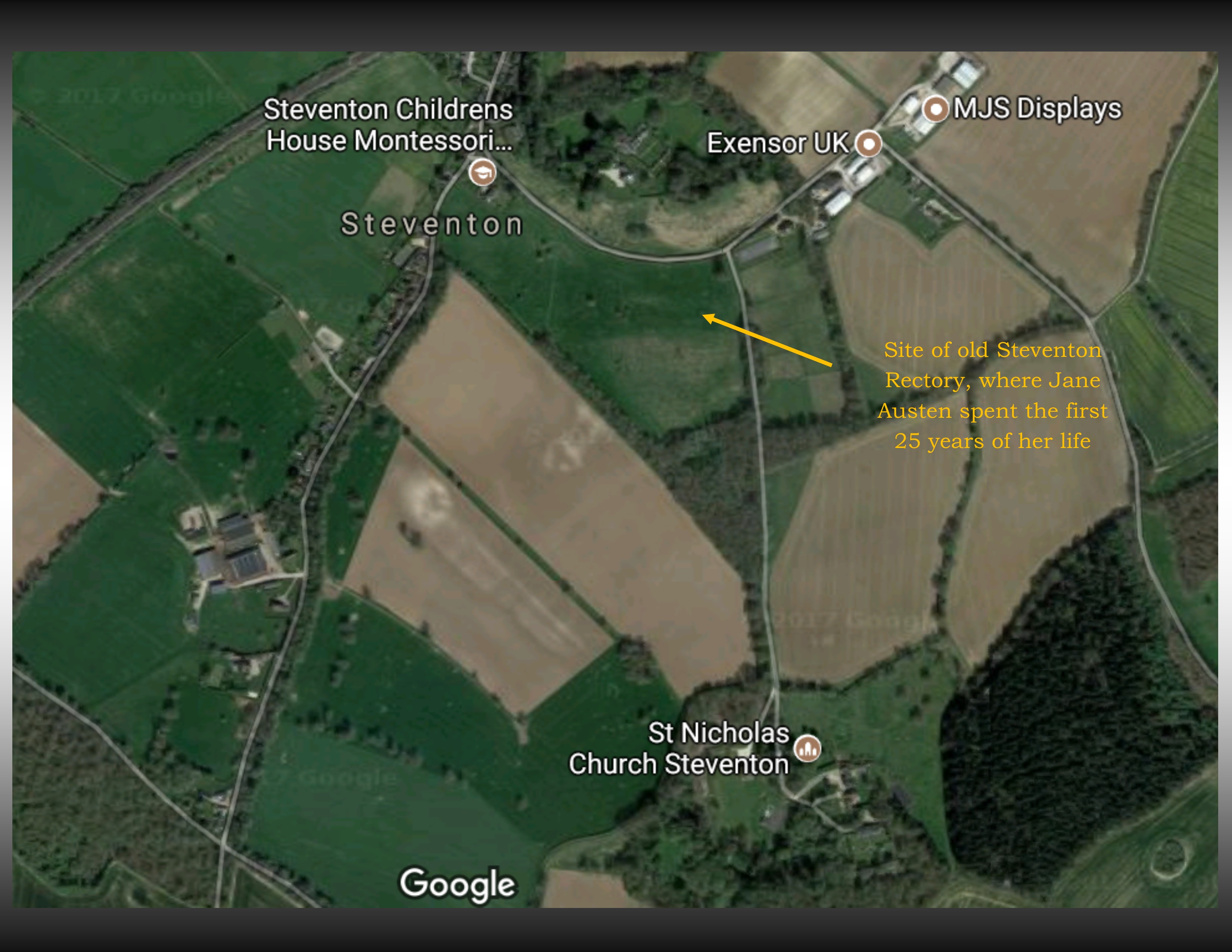

The village of Steventon, top left, the site of the old rectory, and that length of road, the ‘Church Walk’ leading to the church of St. Nicholas at the bottom of the map. Source: Google Maps.

Steventon Rectory: The rectory where Jane lived was situated at a bend in the road from the village. Parishioners would walk past the rectory, turn right and walk down that half mile road we drove on to the Church of St. Nicholas for the services. There’s nothing but a field there today, because the 16th Century rectory was demolished in 1824, when Jane’s nephew, Reverend William Knight, came into possession of the living. Jane had already been dead for seven years by now, and her brother, Edward Knight, built a new rectory for his son William. But, the old rectory, Jane’s childhood home, was inhabited by other members of her family after her father retired from his duties at the church.

In 1801, her father decided somewhat abruptly to leave the ministry and move to Bath and he hurried them all out of the house and westward. Austen père and mère had discussed the move, but it seems to have taken Jane by surprise. She came home from a walk with a friend one day and was greeted with the words, “Well girls, it is all settled. We have decided to leave Steventon and to go to Bath.” Jane fainted at the news, so unwelcome was this idea of leaving her childhood home, the people she had grown up with and grown fond of, and, her father was retiring from his job.

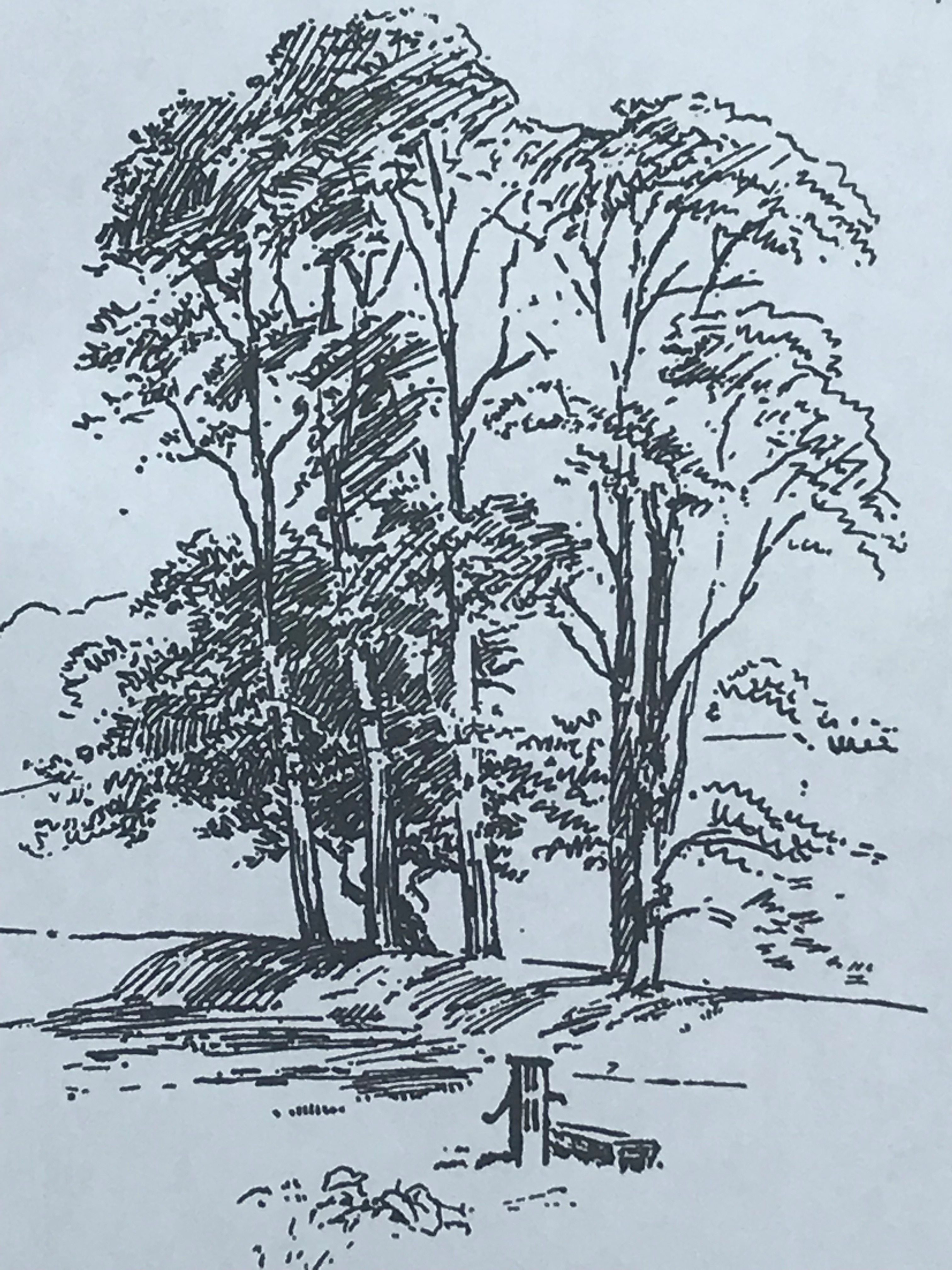

The site of Steventon Rectory in the early 1900s, with the water pump in the foreground, which stood in the washhouse at the back of the rectory. Source: Jane Austen: Her Homes & Her Friends, by Constance Hill.

Jane’s oldest brother James came to live at the rectory with his family—his second wife, and his son and daughter. The boy was James Edward Austen Leigh, who wrote the first official biography of his aunt Jane. (James Edward was the second wife’s son; the daughter, later known as Anna Lefroy, was the child of the first wife and she was about eight years old when they moved to Steventon, and has left us with pen-and-ink sketches of Steventon Rectory (see above & below)). James Austen died in 1819 and the living then descended upon his (and Jane’s) brother Edward Knight’s son, William. (More about this Edward name-change in a future blog post on Chawton Cottage). Edward, or William, demolished the old rectory and built a new one across the road; it still stands and is a private home now.

The site of the old rectory where Jane Austen lived; ‘Church Walk’ on the left. Source: Google Street View.

There’s very little actually known about the old rectory, other than where it was situated, at that corner of the road from the village. In Anna Lefroy’s sketches of the house, there’s a semi-circular carriage drive in front. If the entrance to the drive was indeed at this turning, then it curved right to the front of the house (which faced the main road from the village and north). The path leading to the church on the left goes south. At the back of the house, there was a large garden, a vegetable patch, a sundial, a place to walk, and read and think. Alongside the path to the church was a mud wall, and at the back of the garden, a smooth turf ‘terrace’ on a bit of raised ground that led to a ‘Wood Walk;’ trees and shrubs interspersed with benches.

The house itself must have been quite large. George Austen had eight children, including Jane, and he took in live-in students to augment his parish income. At any given time, there were then, along with some live-in servants (who slept in the attic rooms), fifteen or twenty people in all?

Another view of Steventon Rectory. Source.

The first Jane Austen Biography: There’s no real description of the house either. James Austen Leigh, Anna Lefroy’s stepbrother, in his memoir of Jane, is curiously circumspect about what the rectory looked like, how many rooms it had, and who inhabited the rooms. Consider this: when Jane moved away from Steventon to Bath, her brother James moved into the rectory and lived there until he died, for nineteen years. James Austen Leigh, the nephew, was already born and must have spent most his childhood at the rectory—he knew it well, it was his home also.

But, in the biography, he also narrates Jane’s life in a detached fashion, almost as though he is an onlooker. His account of what the household must have been like is from a distance. It’s true that he didn’t actually live in that house when Jane lived there, but still…he must have known something of what daily life was like, who knocked on door, who brought in the meat from the butcher, where they picked up their mail, what went into the cooking, what grew in the gardens, what the house looked like in summer, in winter, in colorful fall. One possible reason for this detachment is that James Austen Leigh wrote his biography of Jane Austen when he was 72 years old, well, well after his aunt had died and he had himself lived a full and long life. There must have been much he would have forgotten with the passing of the years, and perhaps (true enough) a boy in the house would not have known as much about the fish, the meat and the vegetables as a girl would have.

The entrance to the church of St. Nicholas in Steventon, where Jane Austen attended services.

The entrance to the church of St. Nicholas in Steventon, where Jane Austen attended services.

James Austen Leigh does say that Jane’s life in the old rectory was happy. Jane’s father (and James Austen Leigh’s grandfather) George Austen was an educated man, with a library of over 500 books—veritable riches in those days. They kept a carriage and a pair of horses, which wasn’t as fancy as it seems, because taxes on such property were low, and the carriage was a necessity if the ladies were to go visiting anywhere at all—in rough country lanes, even a couple of miles would have been too long to walk. When not used, the carriage sat in the barn, and the horses were put out to work the plow on the farm behind the rectory, where they grew vegetables, especially potatoes.

Jane puts this bit of information into Pride and Prejudice also, when her namesake Jane Bennet asks for the carriage to go visit the Bingleys (brother and sister), and Mrs. Bennet says most of the horses are wanted on the farm, so go on horseback instead. A storm is brewing, and poor Jane Bennet will be drenched, which is exactly what Mrs. Bennet wants—Jane sick in bed at the Bingleys, and Mr. Bingley attracted enough by the pretty picture of helplessness she makes to offer her marriage.

And then, Elizabeth Bennet, our heroine, walks to Netherfield Park to visit her sick sister Jane through muddy lanes and arrives there with a pretty flush on her face from the cold and damp and two inches of mud on the bottom of her dress. So, Jane (our author) must have also done a fair bit of walking, whether her carriage was available or not!

This ‘back view’ is from the southwest corner of the backyard. I think this is also a sketch by Anna Lefroy, Jane’s niece. Source: Jane Austen: Her Homes & Her Friends, by Constance Hill.

Life at Steventon Rectory: James Austen Leigh, nephew, does give some details although he still does this with a this-is-what-it-must-have-been-like air.

The rectory was large enough to house all the live-in students who brought an added income to the family, but it would have been a bare house. Wooden floors without much carpeting, maybe a single sofa in the parlor, and no knickknacks—no picture stands, scrapbooks, or wax fruit under glass domes. The girls would have had small, mobile writing desks that they could carry from room to room, and a work basket with wool and thread to mend the family clothes and linen for the parish poor. Meals at the dining table would have been adequate, not fancy—a ham, a game pie, some vegetables, maybe a pudding from a family recipe, jealously guarded. No wax candles (tallow instead), no greenhouse flowers, no brilliant cut glass goblets of expensive wines.

Jane did have a small piano, which they had to sell when they moved from Steventon to hired lodgings at Bath, because it was certainly a luxury, and too expensive to move around. It wasn’t until they had settled at Chawton Cottage some eight years later that Jane got another piano, on which she practiced faithfully every morning before breakfast.

In Pride and Prejudice, when our heroine, Elizabeth Bennet goes to visit Lady Catherine de Bourgh at her splendid home, Rosings Park, Lady Catherine offers their piano for Elizabeth to practice on…but not the grand one in the drawing room, instead the pianoforte in the governess/companion Mrs. Jenkinson’s room, because there ‘she would be in nobody’s way…’ There are undercurrents here already before this conversation takes place; Elizabeth has been feisty, disrespectfully teasing Lady Catherine when she asks her how old she is. Elizabeth is so obviously a social inferior, how did she dare such levity in the presence of the great?

Poor Lady Catherine is blissfully unaware at the time that her nephew Darcy (our hero), earmarked for her own daughter, is enchanted by Elizabeth and intends to elevate her into the rarified air which aunt and nephew inhabit. Miss de Bourgh (as all antagonists should be) is a mousy non-entity of a thing who couldhave-wouldhave-shouldhave been a piano prodigy, surely, if only ‘her health allowed her to apply.’ Jane Austen was aware of just how much of an extravagance a good piano was, and perhaps, she had met someone as rude as Lady Catherine.

At Steventon there was enough company around—of their own class—for Jane to visit with. Dinner parties were frequent, and there was a local monthly ball in the assembly rooms at nearby Basingstoke. The balls, the dancing, which figure so frequently in Jane Austen’s novels, were courting and mating rituals in England, where the young met other young and decided who was to be in love with whom and who was to marry whom. Dinner parties also ended with impromptu dancing sessions, with someone ineligible roped in to play the piano while the eligibles danced and courted. Jane must have seen this, at least when she was young herself and dancing as much as she could.

The Musicians’ Gallery in the Bath Assembly Rooms, where Jane undoubtedly danced. Source: Jane Austen: Her Homes & Her Friends, by Constance Hill.

In Persuasion, Anne Elliot, at twenty-seven years of age, finds herself at the piano on one such evening, while the other younger, wilder ladies dance with the most eligible man in the room, Captain Wentworth. It’s a humiliating experience for Anne. Wentworth is an erstwhile lover, whom she rejected eight years ago, mistakenly, of course, because she’s still in love with him. But, he’s now flirting with other lovelies, Louisa Musgrove in particular, whose only advantage over Anne is her youth, silliness and flightiness. But, perhaps Wentworth wants a giddy wife now, after he’s made his fortune, and the ‘old’ Anne Elliot, sober and intelligent, is no longer to his liking. This is what Anne is thinking so painfully in this scene, and perhaps Jane Austen observed this, or something like this at the end of a dinner party.

The Help at the Rectory: While the Austens were not poor, they would have only had a few servants. Inside the house, a cook, perhaps a parlor maid to hand out food at the dining table, a manservant who did the heavy lifting and cleaned the boots, and a maid to do the dusting and mopping. Outside, in the garden, there would have been an ‘outdoor’ man to help Mrs. Austen, and there was a bailiff, John Bond, who oversaw the farming on the glebe lands and the rented Cheesedown Farm. Mrs. Austen also had cows and a dairy for the family milk, cheese and buttermilk, so she would have had a dairymaid, but most likely did most of the other dairy work herself.

The south side of the Church of St. Nicholas, where George Austen was rector.

Jane’s father George held the livings at Steventon and Deane and they brought him a little more than two hundred pounds a year together. He had to supplement by taking in pupils, who lived with them and studied with Mr. Austen to prepare to matriculate at one of the two universities then, Oxford or Cambridge. Mr. Austen was an Oxford man.

It was from her own childhood and her father’s hard-earned income, adequate but not rich, that Jane drew inferences in Pride and Prejudice, when the already-hated Mr. Collins (because the Bennet estate is entailed to him) comes to visit, and becomes more detestable for his ridiculous, simpering ways. Collins is determined to do the ‘right’ thing by marrying one of the Bennet girls so they needn’t feel the pinch of losing their home to him, and is over effusive in praise of everything, and when an excellent dinner is served, he asks Mrs. Bennet which of her daughters made the food with her fair hands? To which, Mrs. Bennet answers with some ‘asperity’ that they kept a cook, and her daughters need not toil in the kitchen, thank you very much.

The east window at the Church of St. Nicholas, Steventon.

However, Jane and her sister Cassandra did engage in some other fairly menial work—spinning flax or wool. James Austen Leigh remembers two spinning wheels in his family. Unlike the work of the cottage women, the spinning wheel that Jane used was an elegant wood machine, he says, with a shining wheel on one end, and a spindle on the other. Thread was formed by moistening it, and Austen Leigh says that a bowl of water sat beside the spinner, while the cottage woman ran the thread through her mouth. He paints a picture of a genteel occupation, picturesque, much as a graceful woman might bend over a harp in the parlor for the entertainment of admiring guests. What he forgets to say is that the Austen ladies made almost all the clothing for the Austen men, especially their shirts, and spent almost every evening at work by the flicker of a candle.

Such then would have been life at the old rectory when Jane lived there. And every Sunday morning, at least, the entire family would take that ‘Church Walk,’ half a mile down a dusty or slushy road, according to the season, to the little church at the end of the lane.

When we visited the Church of St. Nicholas, there was no one else around. After a bit, the family went off to run an errand, and left me there in blissful solitude. I taped the video, listened to the sounds of the birds and the bees, and walked around the churchyard for a while in that sunshine, reading the names of the Austens and others in the tiny churchyard. And then, I went in again.

If you’ve enjoyed reading this, please consider sharing by emailing a link to the post, and by hitting the social media share buttons below, so others may read also. Thank you!

On the next post—we visit the Church of St. Nicholas at Steventon—The Austens in the churchyard—Not Northanger Abbey: Jane Austen, Steventon, and the Church of St. Nicholas—Part 2

6 Replies to “Not Northanger Abbey: Jane Austen, Steventon, and the Church of St. Nicholas—Part 1”