(Part 1 here)

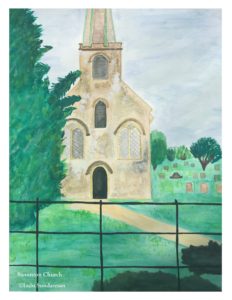

A half a mile south of the old rectory is the Church of St. Nicholas, where Jane’s father preached and led his flock, and where she attended services. It’s also another smooth, macadamized road today—in Jane’s time, it would have been a rough path, slushy in the rains, dusty in dry summers.

The church dates to the 12th Century, so it had been standing there, among the fields and the pastures, for almost seven centuries by the time George Austen came to Steventon to be rector. The warm southern wall of the church, right of the entry door, hosted purple and white sweet-smelling wild violets that bloomed in summer. The close-cropped green of the churchyard was shaded by elms, hawthorns and a mighty, aged yew, which had probably been there for as many years as the church itself.

There’s no real parking lot in front of the church, maybe five or six spaces, but parking’s not a problem on the day we visit; there’s one other car, that’s it. We’ve just come from visiting that mighty Salisbury Cathedral (Part 1 here; Part 2 here) and will go on to visit other big cathedrals at Winchester and York. This church is tiny compared to them, all by itself in the fields, basking in that sweet sunshine, a few trees casting shadows on the churchyard and its time-dappled gravestones.

On the western front, there are three small windows, and a single door for the entrance under a rounded archway. The front is weathered, splattered and blotched with age, and the spire is made of wood, finished with copper strips turned blue-green by the sun and the rain. In Austen’s time there was no spire, merely the turret.

Steventon church is famous for its association with Jane Austen. She prayed here for the first twenty-five years of her life, sat on the pews with her brothers and sister, and her father conducted the services in his capacity of rector. The church board, in the front near the parking lot, displays a small Jane Austen icon—a lady seated on a chair, with a small, round table in front of her, a quill in hand, writing, presumably. There is a lovely plaster statue of this icon in Winchester Cathedral—more on that on the post on Jane’s final resting place. (And, my blog post painting is of this plaster statue).

Inside, there’s a small porch to keep the cold out as the worshippers came in for the service—you entered, shut the door, and then opened the door into the main church. It’s a small church, so one part of this porch, enclosed by a door, was the vestry.

The JASNA tablet in the front porch.

Jane Austen has an enduring, and worldwide legacy, and a lot of the money in preserving these elements of her life has come from her readers and admirers in North America. In the porch is this brass tablet acknowledging a grant from The Jane Austen Society of North America to help refurbish the church bells.

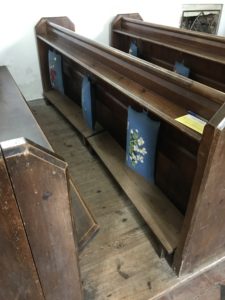

Inside the Church: Inside, there’s the nave, not big at all (and again, I’m comparing this to the cathedrals which were mammoth) with ten pews or so on either side. Just as you enter, on the right is a wooden closet of sorts, the woodwork fretted and designed to provide privacy—this was the squire’s pew of yore, when the local lord of the manor would bring his family here, to watch and to listen to the service. It has been moved almost certainly from the 18th and early 19th centuries when Austen worshipped here–then, the squire’s pew was up in front, against the chancel.

Looking back at the front entrance, the Squire’s Pew is on the left. This picture also gives you a sense of how small the church is; I was standing at the entrance to the chancel when I took this picture.

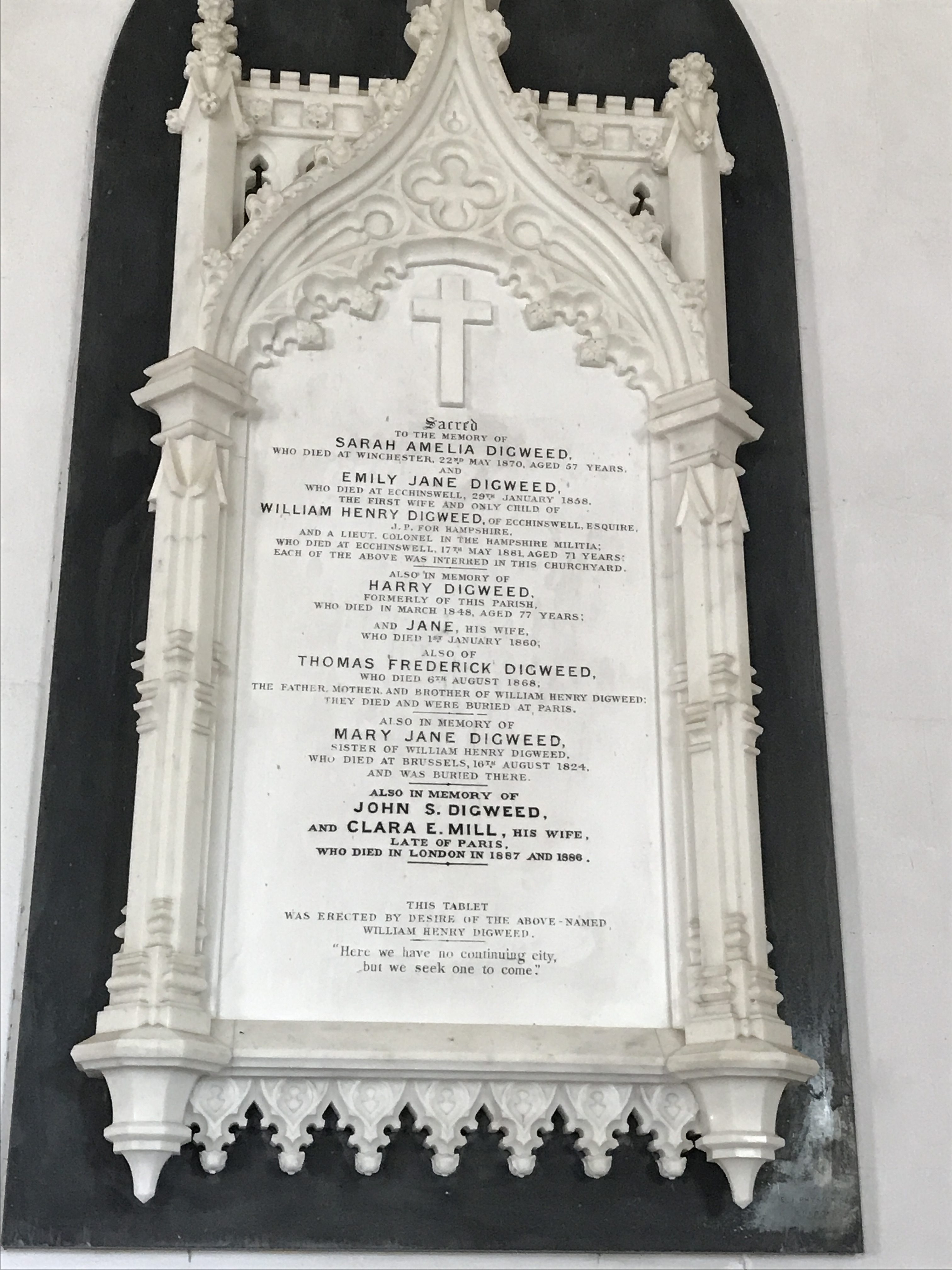

In Jane’s time, the squire was her father’s cousin, Thomas May Knight, who had given him this living, and made him rector of Steventon Church. (Knight’s son adopted Jane’s brother Edward, more on that in the Chawton Cottage blog post). But, Thomas May Knight did not live in Steventon or inhabit the manor, instead, a family called Digweed rented the manor, opposite the church, for over a hundred years. The Digweeds then would have occupied this squire’s pew. A testament to their tenancy is the marble memorial tablet on a wall of the church, filled with Digweed names.

Outside the church, there were many engagements between the Digweeds and the Austens. In a letter to her sister Cassandra (who is away from home then), Jane is struck with the idea that one of the Digweed sons, James, must be in love with Cassandra, because he comes to visit, stays a while and talks all the time of Cassandra and when she’s coming back. Despite their proximity, however, Jane herself doesn’t seem to have fallen in love with any of the Digweed sons. Also, Austen père and Digweed père pooled their money together to buy sheep (in an economical bulk) for their pastures.

A closer view of the Squire’s Pew, left. And right, a sketch of the Squire’s Pew in about 1901. From Jane Austen: Her Homes & Her Friends by Constance Hill.

I think not much has changed in the church, or its structure, since the time it was built in the 12th Century, or when Jane went to the services there. The lancet windows–three each on the northern and southern walls–are deepset, with narrow panes that let in shards of light.

This window is in the south wall of the church, and the fireplace (one of a few) is, I think, left of the chancel.

There are a few fireplaces embedded into the walls. Both the style of the windows and the fireplaces must have been constructed to keep the church warm. Now, there’s electricity and central heating, then, a draft would swirl around feet and chill hands whenever a latecomer opened the door to the church (the porch notwithstanding), and however thick the walls, it must still have been cold, fingers, toes and noses.

I’m fascinated by the tilework on the floors; this is unlike any other church we visited in England. It is said the church is much like it was when Jane Austen lived at Steventon, then the tilework dates back 200 years, and, quite possibly, also the pews with their little kneeling cushions hung on the back of the pew in front.

While the church is filled with memorial tablets to the Austens and the Knights (who were also immediate family because Edward Austen, Jane’s brother, became a Knight by adoption), there’s a single brass tablet on the north wall for Jane. It’s simple, it’s elegant, and for me, that’s all the notice they need take of her, because I’m here to see the place where she worshipped, the village in which she lived, imagine the rectory in that empty field with cows munching on the grass. I’m here for the place, and even if the tablet weren’t there, it would be just fine for me. Because, I know.

The Jane Austen tablet on the north wall of the church, the only mention of Austen, well, ok, other than the icon on the church board outside and the JASNA tablet in the front porch.

Just before the chancel is a small, wooden pulpit and a small altar. The way to the chancel is through three pointed archways, two false on either side, the middle one the actual entrance. Patterned painting in orange and green flourishes on the archways—I think it was uncovered during a renovation, and must have been very much like what Jane saw when she was here.

The pulpit, left of chancel; the small altar, right of chancel, and the painted archway leading to the chancel at the Church of St. Nicholas.

The chancel is tiny, with a small organ about as big as an upright piano, a small place for the choir (maybe five people singing altogether?) and an altar under the stained glass east window. The main altar is a painted wooden cabinet, beautifully done, and the red and black tiles carry through from the nave into the chancel.

The east window and the main altar at the Church of St. Nicholas.

The Austens at Steventon Church: Also in this space are a series of marble tablets memorializing the Austens and the Knights. Jane’s father is not mentioned here, because he retired from Steventon and took his family to Bath for the next four years he lived. He died in 1805 and is buried in Bath.

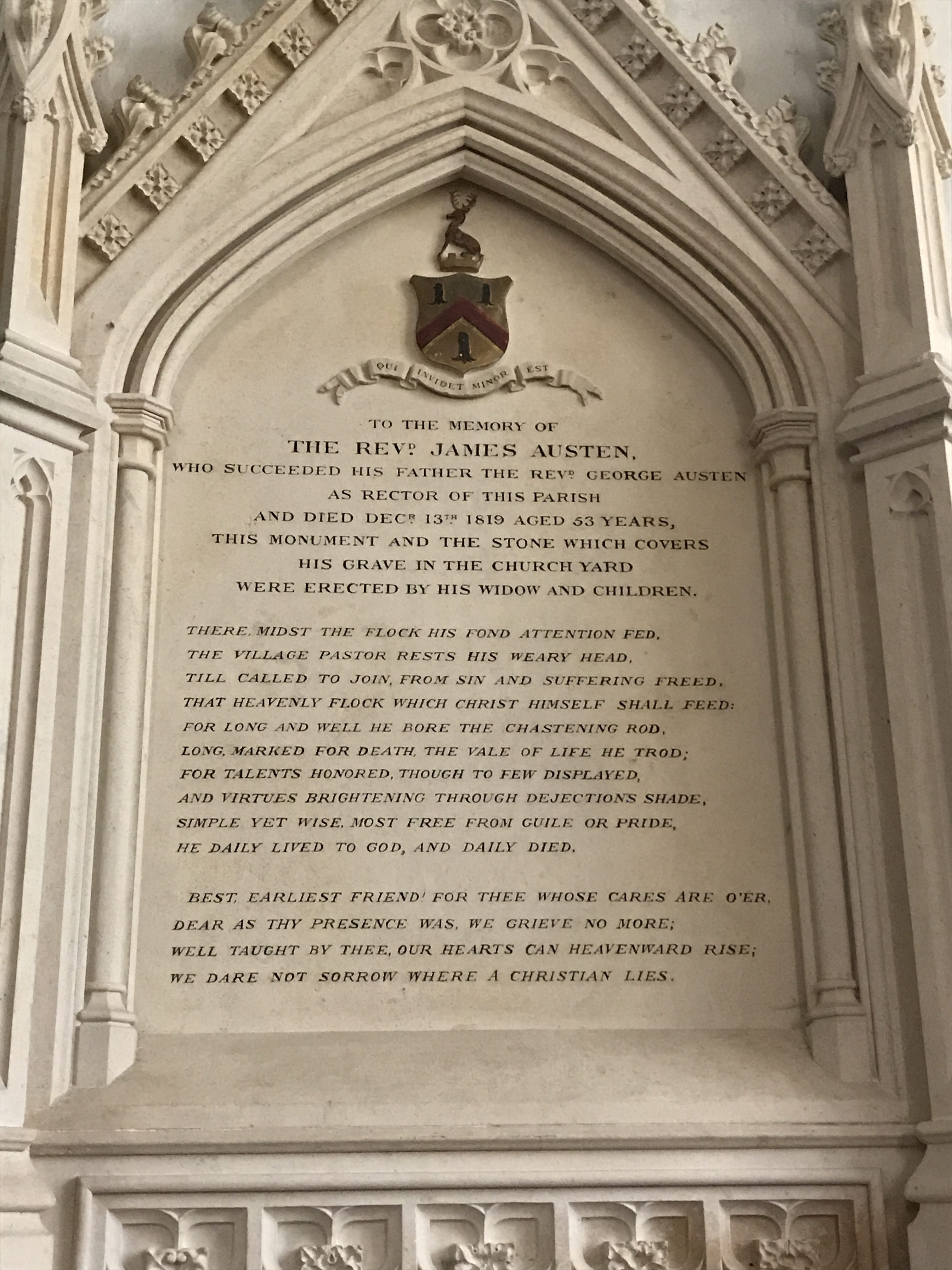

The next person to become rector was Jane’s oldest brother, James Austen, until his death in 1819. There’s mention of him.

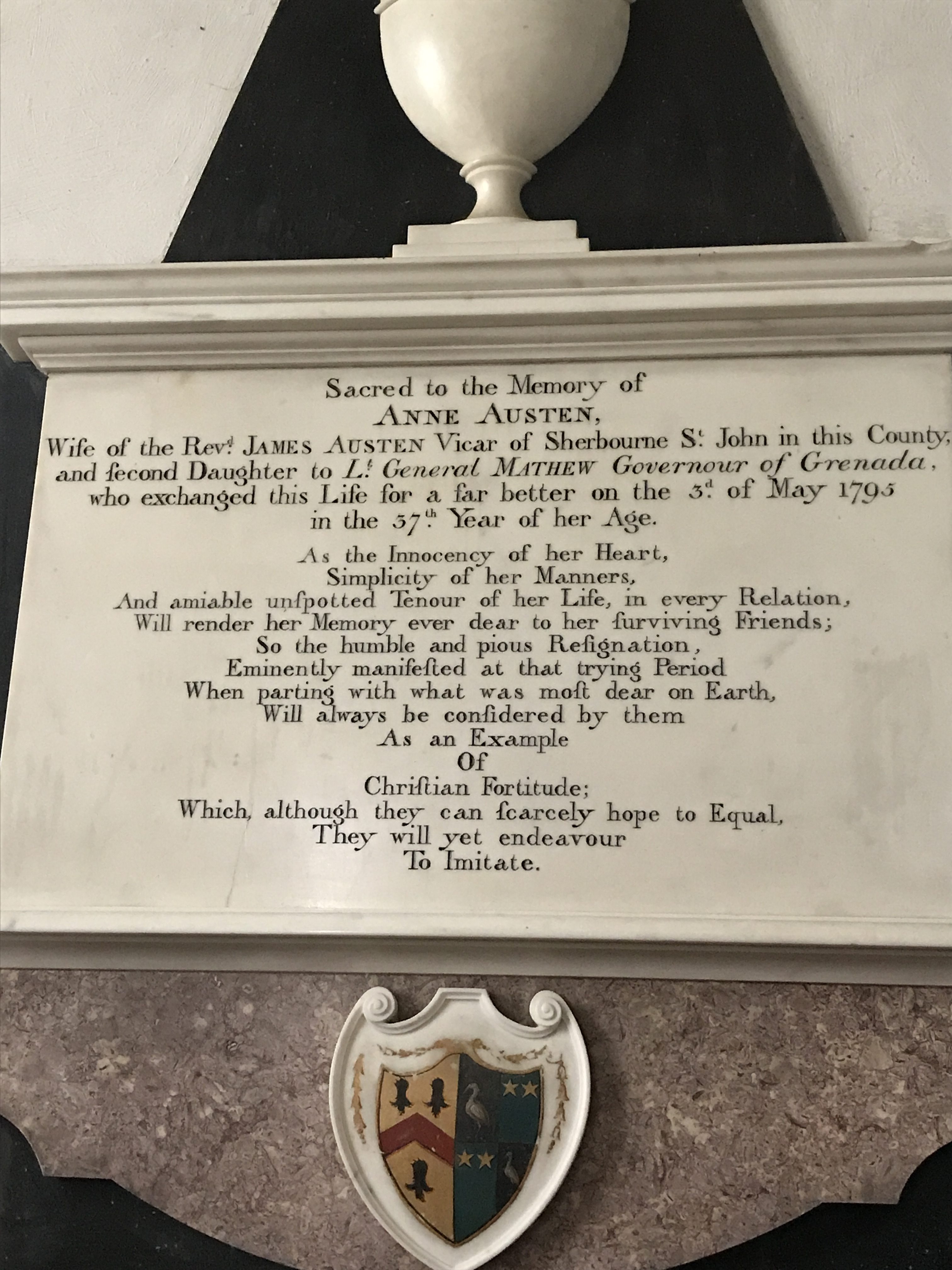

And, his first wife Anne Austen, who had died before he came to Steventon as rector, with his second wife. (Anne Austen died at neighboring Deane where James and she were living at the time). This tablet is on the south wall of the nave. Note Anne’s age when she died in 1795; she was thirty-seven. Her daughter Anna Lefroy was only two that year, her husband would have been thirty—seven years younger than his wife. Anne Austen then had married late, and had a child at thirty-five, also very late for those times.

Anne’s daughter, Anna Lefroy, lived at the old rectory twice—the first time when she was sent to Steventon and the care of her aunts Jane and Cassandra after her mother died, and the second time, when she came to live here after her father became rector of Steventon. Anna’s the one who sketched the views of the old rectory as it was before it was demolished—this was a house she knew well, and grew up in.

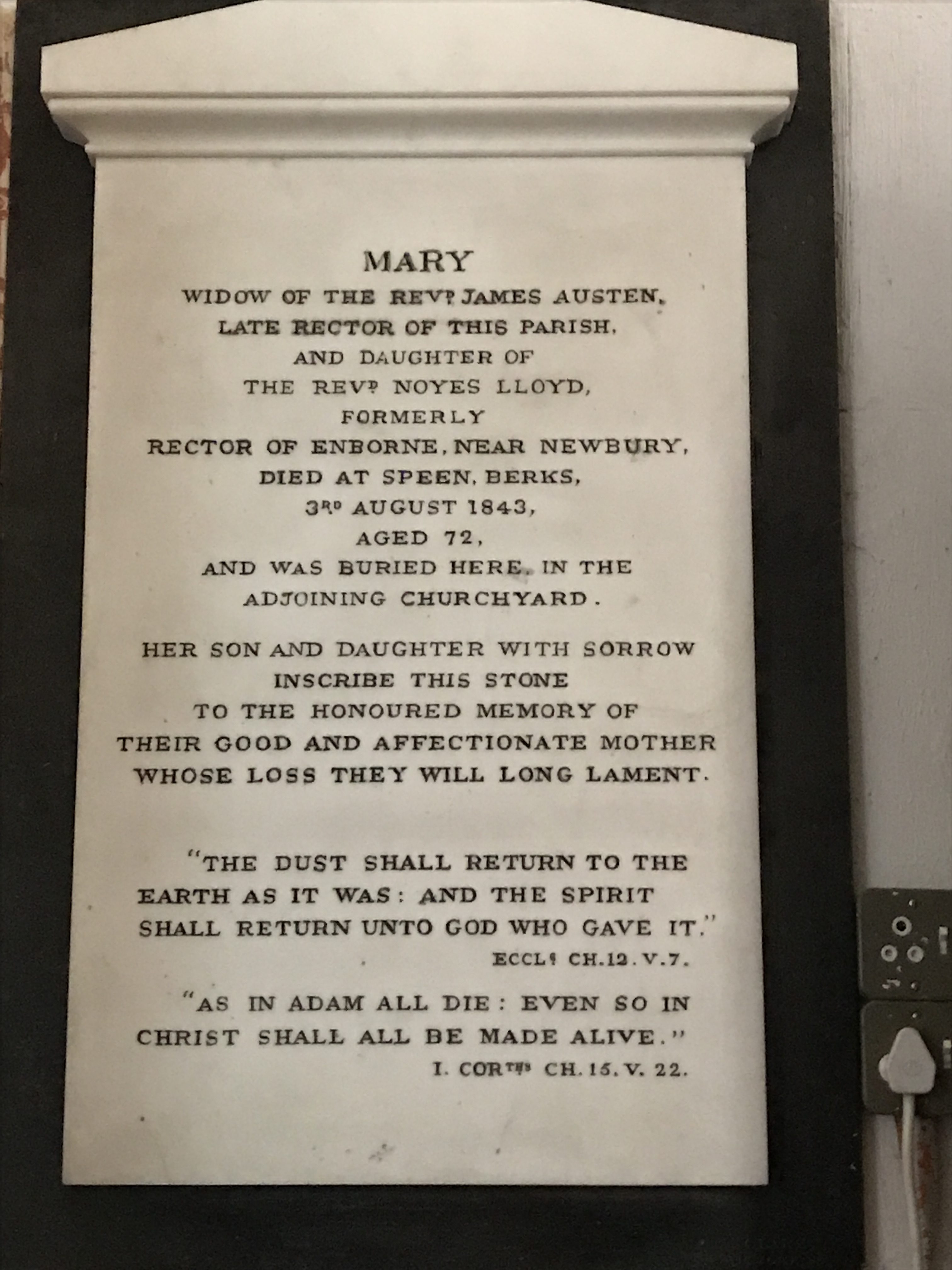

In the chancel is also a memorial to James’s second wife, Mary Austen, who he married two years after his first wife’s death, and with whom he lived at the rectory until his death. Mary gave birth to James Edward Austen Leigh (who wrote the first official biography of his aunt Jane) and a daughter, Caroline, both of whom placed the tablet in Steventon church in her memory. Incidentally, Mary’s sister, Martha Lloyd, was Jane Austen’s lifelong friend—so much so that Martha moved into Chawton Cottage with Jane, her sister Cassandra and their mother and lived with them.

The Knights are also in Steventon Church. Remember that it was Thomas May Knight, a cousin of Jane’s father George, who gave him the Steventon living, and later, Thomas May Knight’s son (Thomas Knight) adopted one of Jane’s brothers, Edward, and gave him their estates at Godmersham, Chawton and Winchester. Eventually, Edward Austen had to take the Knight name also. When James Austen died in 1819, the living reverted back to the lord of the manor, and this time, the Knight who owned the living was Jane’s and James’s brother Edward Knight. He gave the living to one of his sons, William Knight, who was Jane’s nephew. And so, the Knights came back to Steventon. William Knight found the old rectory—where Jane had lived—too small, or too inconvenient, and this is when he demolished it, and built a new rectory across the street.

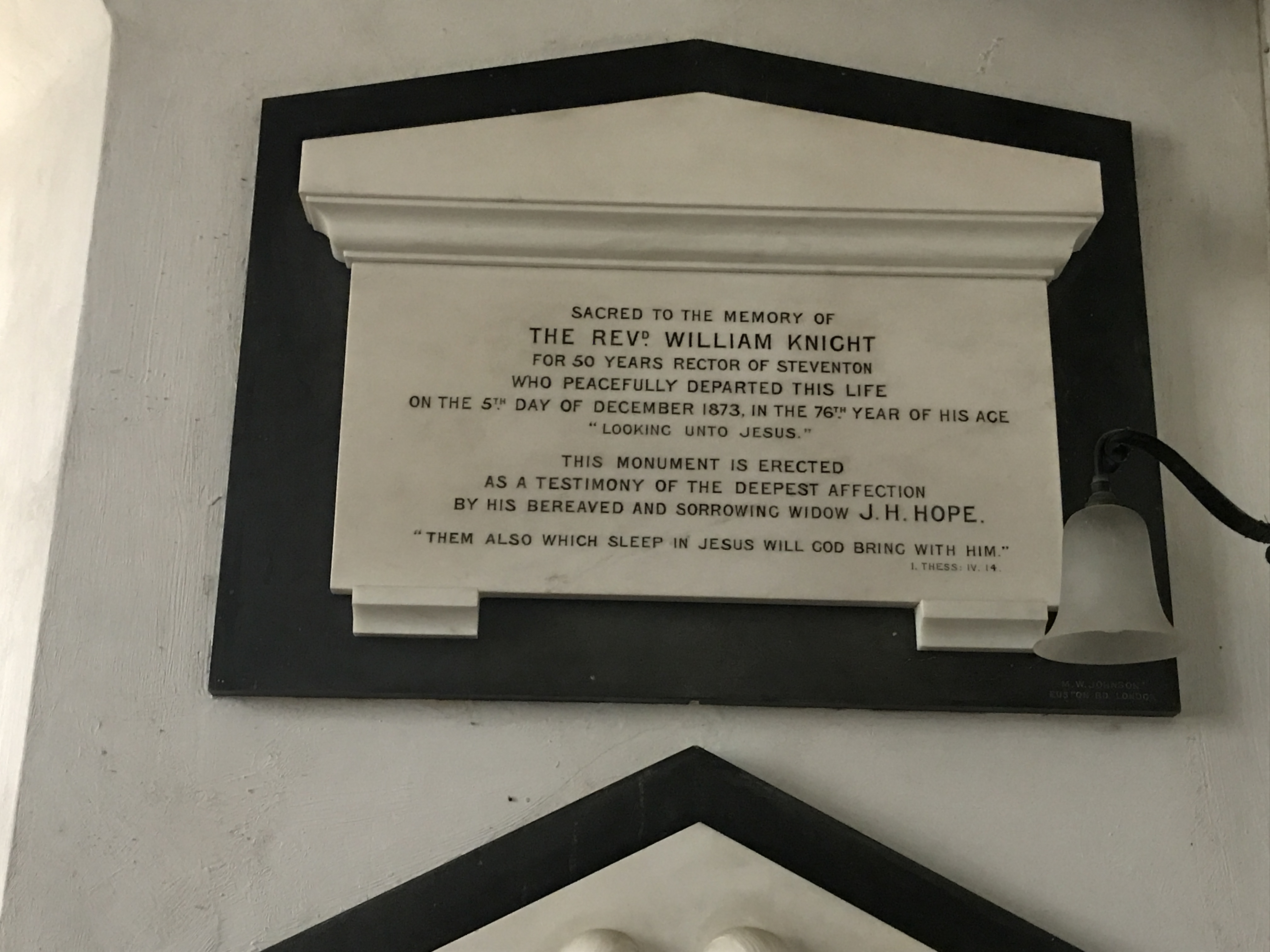

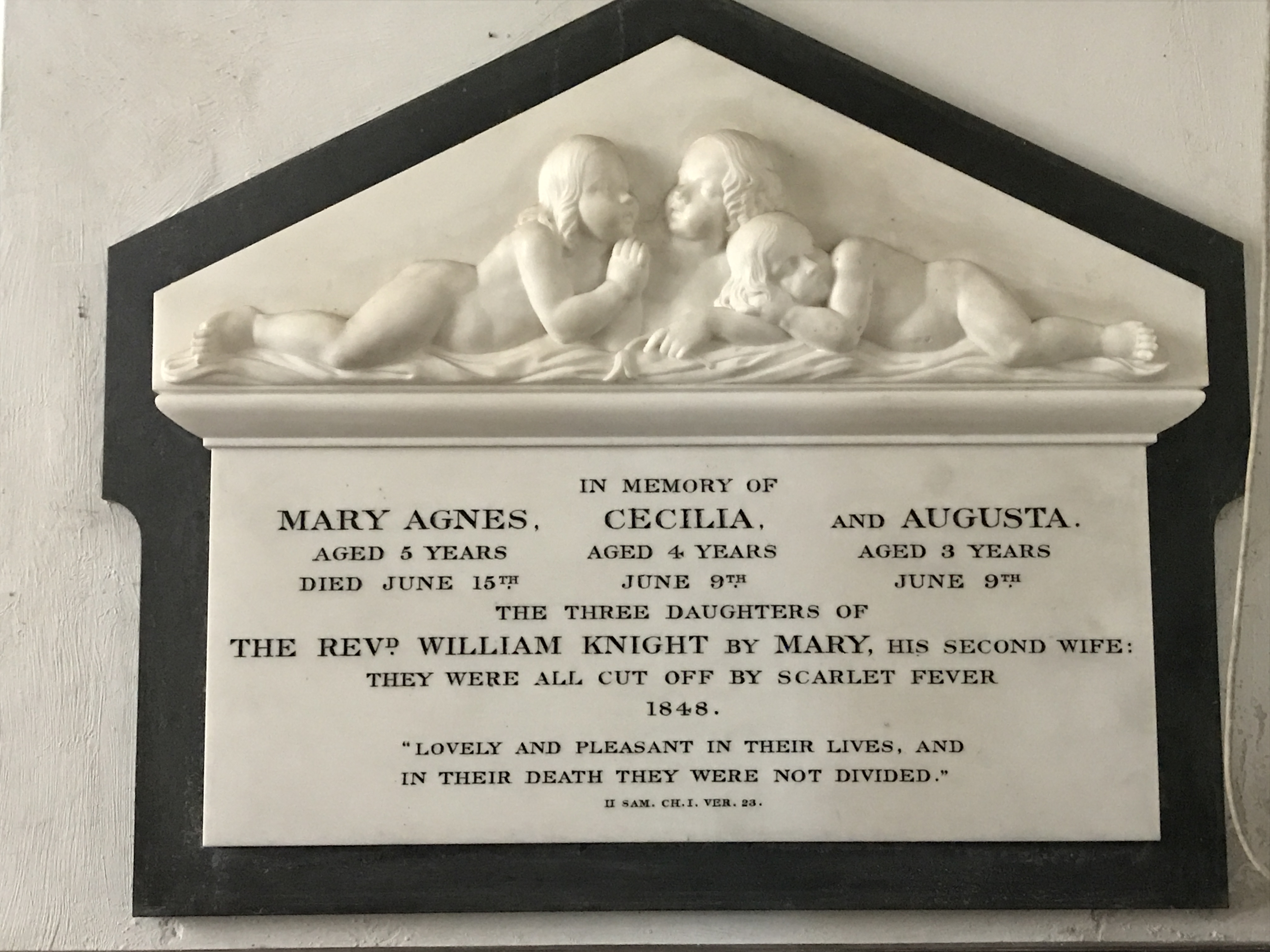

William Knight is memorialized in the chancel, but also, there’s a memorial to three of his very young daughters, who all died in the space of a short week of scarlet fever in 1848.

Outside, I wandered around the churchyard, looking at the gravestones. On the left of the church, the north side, I find the graves of James Austen and his second wife, Mary, who must have been buried alongside her husband when she died.

James Austen (Jane’s oldest brother) and his wife, Mary, buried in the Church of St. Nicholas churchyard.

The three young daughters of William Knight also rest here. And, curiously enough, although they died well apart in years, William Knight’s two wives, the first, Caroline, and the second, Mary, lie side by side.

The graves of William Knight’s (Jane’s nephew; her brother Edward’s son) three young daughters, left, and his two wives, right.

Steventon, even today, has a mellow, slow-world vibe. We visited on another brightly sunny day—hot, actually—and the village slumbered in the warm sun, and the trees cast shadows around the churchyard. And here, is where Jane’s ideas incubated. Here, in this little village, still little, Jane Austen met all those varied people who would become prototypes for her distinct characters. And she watched them, she studied their mannerisms and their eccentricities, pondered on their motivations, and then put them down on paper.

James Austen Leigh, Jane’s nephew and first biographer, says that the Steventon countryside is not ‘picturesque;’ there are no high mountains or deep valleys, but only gentle rolling hills, and no grand views that go on for miles and miles. I, respectfully, disagree.

It’s hard to explain the beauty of the place. Now, months after the trip, I have an impression of yes, those gentle sloping hills covered in green, but also the trees throwing speckled shadows on the roads, the cottage and house gardens bursting with flowers, the bees buzzing around in the warm air, the sun laying golden light everywhere. I remember the peace surrounding the church, the fields stretching greenly away behind it, the gravestones tilted this way and that, and walking around searching for the graves of the Austens.

It is a quiet countryside, time seemingly measured by the passing of the sun, cows in the meadows, sheep munching on the turf, and here Jane Austen, more than two hundred years ago, wrote the best known of her books. Before they left Steventon, Jane had completed Pride and Prejudice (initially known as First Impressions) and Sense and Sensibility (Elinor and Marianne) and a part or the whole of Northanger Abbey.

I can see why Jane was distraught at having to leave Steventon, and how the next eight odd years of her life, as they moved from one lodging to another in Bath and other places, never gave her the peace to write…until they moved to Chawton Cottage and the writing began again.

If you’ve enjoyed reading this, please consider sharing by emailing a link to the post, and by hitting the social media share buttons below, so others may read also. Thank you!

On the next blog post—At Home at Last: Jane Austen in Chawton Cottage—Part 1—where Jane Austen spent the last eight years of her life.

Hi

I really enjoyed your memories of your visits to Steventon church and surrounding areas.

I have been three times in the past and now we are taking our daughter and granddaughter.

The reason we are so interested is because I am being a Digweed related to the Digweed families. I am hoping to find that way back a Digweed married a Austen it’s quite feasible as the two names were so involved in each others lives. One instance was a Digweed went into partnership with a Austen to purchase a flock of sheep.

Looking forward to visiting Steventon next week.

Best Wishes

Barry Digweed

Hi Barry,

Very cool that you are related to the Digweeds at Steventon! For others reading this, a quick recap: Hugh Digweed rented Steventon Manor House opposite the Church of St. Nicholas, and the Austens knew them for a great many years.

Mr. Digweed, a tenant farmer, also rented the Manor Farm and quite a bit of land in the parish from the Knights (who were owners of the property and it was through a Thomas May Knight that Mr. Austen got his living at Steventon).

Now, for you, Barry: A Richard Digweed and his wife, Amy first rented the Steventon lands and manor in Michaelmas of 1758. At some point, that tenancy transferred to Hugh Digweed, and I’m not sure how Richard and Hugh were related. But Hugh Digweed was tenant when Mr. Austen first came to take up his living in 1764 (he got it in 1761 but did not move to Steventon until after his marriage in 1764).

Hugh Digweed had six sons–one, called James, Jane Austen teases her sister Cassandra about–nothing comes of it. Jane herself, perhaps, very perhaps, could have been interested in another son, Harry (right age group), but again, there’s nothing to substantiate it–she does not marry eventually and he marries Jane Terry from nearby Dummer House, whose father was squire of Dummer.

James Digweed ends up marrying Susannah Lyford, daughter and sister of Basingstoke physicians/surgeons.

The Digweeds stayed on at the manor and farm well after Jane Austen left Steventon (in 1801) Harry takes over the management of the farm along with his brother William-Francis, I think.

So this is about the connection between the Austens and the Digweeds–nothing before Jane Austen for sure, and, as far as I know, nothing after, in later generations.

Enjoy your visit to Steventon! I wish I could go back there so easily!

Thank you! What an informative and entertaining article. I greatly enjoyed it.

Thank you! Glad to hear you enjoyed reading it.

Beautiful narrative! Thank you for sharing. Are any distant family members of the Austin family, alive today?

Hi Poonam, yes, of course there are. I didn’t go searching for contemporary descendants in writing the blog posts, however, I did stumble upon articles on the JASNA website by the founding editor of their online Persuasions magazine, Joan Austen-Leigh, whose great-grandfather was James Edward Austen Leigh. I mention him in this blog post as the nephew of Jane Austen who wrote her first, official biography. (His name change to Austen Leigh came later, when he was left an inheritance by Mrs. Leigh Perrot, who was his grandaunt and Jane Austen’s aunt on her mother’s side).

Here’s a link to articles on Jane Austen on the JASNA website by Joan Austen-Leigh.