We last left Jane Austen at Chawton Cottage, Part 1, Part 2 and Part 3. Jane’s most productive writing periods were pre-Bath (before 1801) and after the move to Chawton in 1809. The first produced Pride and Prejudice, Sense and Sensibility and Northanger Abbey. During the second, she wrote Mansfield Park, Emma and Persuasion. She also began publishing in this Chawton period, beginning with Sense and Sensibility first.

Chawton Cottage was the hub of comfort for the extended Austen family. Here, was Mrs. Austen, the mother of Jane and her siblings and grandmother to their children, and the two beloved maiden aunts, Jane and Cassandra. And, the nieces and nephews came to stay, sometimes for a vacation, sometimes for longer when there was a death in the family and they needed a place to be and someone to cheer them up.

Source: Google Street View

‘Aging’ and Ailing: Sometime in 1815, Jane had begun work on Persuasion, initially titled The Elliots. She was thirty-nine years old herself; Anne Elliot in the novel is twenty-seven, had rejected a very worthy lover, Wentworth, who returns after eight years made a captain in the navy, rich, and still eligible. But, Anne, her looks faded at the ancient age of twenty-seven, is no longer thought of as being on the marriage market.

It’s an age-old story—men age gracefully (and money makes them more attractive) while women…they just grow old. Perhaps, Jane was thinking of her own life, an early love affair with Tom Lefroy, and her rejection of a perfectly good marriage offer (from someone else) because she had not loved the man, and then gave Anne Elliot a second chance, because she does love Wentworth. And because, while sometimes life imitates art, art can be manipulated to create happy endings that life doesn’t often provide.

By early 1816, even though Jane—in her letters—speaks of rides in the rain in a donkey carriage, she was also unwell . Her beloved brother, Henry, had been very sick—in mortal danger—during the last half of 1815, and Jane had been in London looking after him. At one point, she had thought it necessary to tell her siblings to come to his bedside, and her sister Cassandra, and brothers James and Edward had made the journey to be with Henry, in what they had thought would be his last illness. But, Henry recovered, somewhat miraculously, getting better as fast as he had fallen ill. The Austen siblings all went home, but their emotions must have been roiled at such a close call—for which the only documented reason given was a ‘low fever,’ which is just about anything and tells us nothing.

Jane was very fond of Henry—he was her favorite brother, and the strain of nursing him began to tell upon her after her return to Chawton Cottage.

Whatever was ailing her, Jane finished Persuasion in mid-to late1816 (perhaps around the time that she wrote to her nephew, Edward Austen, about the donkey-carriage ride) and went to bed that night very unhappy about the ending. It had to be changed, it needed to change, but how? She was exhausted; all those little illnesses had taken their toll, and finishing a book brings its own mess of tiring excitements, especially if you don’t like the way it ends. But, the next morning she woke to discard that last chapter and write two more (over the next few weeks) which fit better into exactly how the ending should be—and which ended up in the published book.

Jane kept Persuasion secret all that fall of 1816—perhaps Cassandra knew of the novel, but even Henry did not.

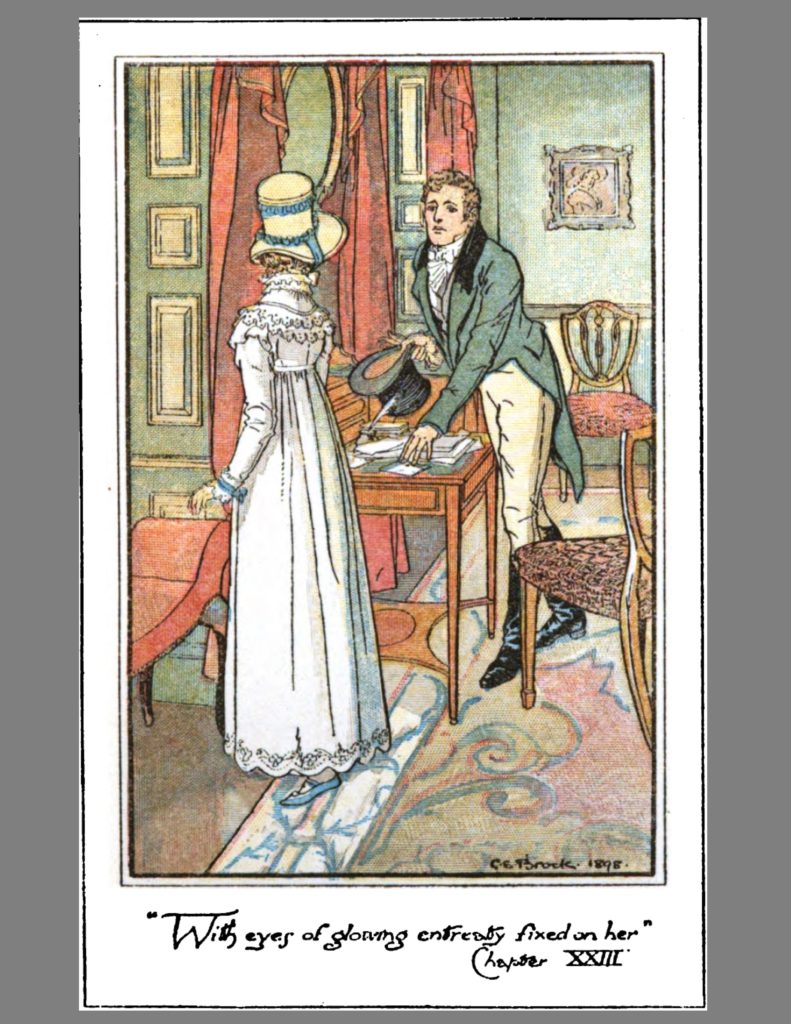

Source: Illustration by C.E. Brock in the 1895 edition.

In September, 1816, she wrote the last of her surviving letters to her sister Cassandra. It’s possible she wrote others and Cassandra destroyed them as too personal, or that they were never again parted until Jane died the next year. In this letter, Jane mentions her back pain as being much better. And, as usual she makes light of it. Her back hurt not from fatigue but from the agitation of parting from her beloved Cassandra. And, Dr. White is going to call on Jane, so she is determined to work herself back into a ‘beautiful’ state to receive him.

In January of 1817 she wrote that she has nursed herself back to health over the winter. Or so she said, anyhow. Read Austen’s novels (or indeed, her letters) and the idea of physical exercise, of being outside and inhaling the fresh air, and walking over fields without regard to mud and wet (like Elizabeth Bennet in Pride and Prejudice) was of importance to her, and so she made her heroines equally enchanted by the walks. They rarely sat down to needlework, and if they did sit down, it was to read (the heroines, that is). But, Jane writes in her letter that it is not donkey-carriage weather in the winter, and the donkeys are in idle luxury and in danger of forgetting why they’re getting their meals. So, for all of Jane’s bright assurance that she was getting well, she was obviously not outside in the cold—in other words, not that well at all.

However, Jane did begin a new novel, titled Sanditon, and wrote twelve chapters of it from the end of January, 1817, until she absolutely could not work anymore. The last date on the manuscript is March 17th, 1817 and that was the final time she picked up her pen.

What was ailing Jane? She didn’t know. She had rheumatism in her knee, and when she recovered, a little twinge of pain was left “to make me remember what it was.” And, she was then able to move about a bit more in the neighborhood visits, well enough at one point to consider riding their donkey, so the carriage didn’t need to be taken out each time, the horses harnessed, and Cassandra could walk by her side and get her exercise also.

She thought it was bile also, a stomach complaint, and nursed herself for that for a while, as she mentions in her letters.

Jane wrote letters to almost everyone she knew. I’m not sure when she found the time to work on her novels. Consider this, she ran the house with her sister, numerous nephews and nieces came to stay with them—perhaps Chawton Cottage, small as it is, was never inhabited by only the four who had moved in there; someone else was always visiting. So, they had to be looked after and entertained. And given the sheer number of people Jane wrote to, as evidenced by her surviving letters, a large chunk of every day must have gone in this occupation. And then, there were the visits to the poor, teaching their children to read and write, and the mundane—tending to the garden, ordering the coal, talking to the butcher.

Funny Jane: She wrote to her nephew, James Edward Austen Leigh, that winter of 1816. James Edward was her brother James’ son and lived in the old rectory in Steventon where Jane had spent the first twenty-five years of her life. (He’s also the author of the first official biography on Jane Austen). In a letter to him, Jane talks of James Edward losing two and a half chapters of his work at Steventon rectory. It’s a good thing, she says jokingly, that she hasn’t visited Steventon recently, or suspicion might have fallen upon her. Jane, this torridly famous author, is kind to her nephew—two and a half ‘twigs’ she could have stolen from him to build her own ‘nest,’ but his work, so vigorous, could not have been of help to her writing. Implied is that he was so much better than her.

In April, 1817, Jane suffered from numerous fevers, on and off, and a ‘bilious’ attack again. By the end of that month, the Chawton Cottage inhabitants could not any more host family members. James Edward’s sister goes to Chawton at this time, but has to stay with another family and not her aunts and her grandmother, because Aunt Jane is too ill to have her in the house. She does visit her in her bedroom though, and Jane rises to greet her and they talk for a while, until Cassandra shoos her out of the room.

Source: Google Street View

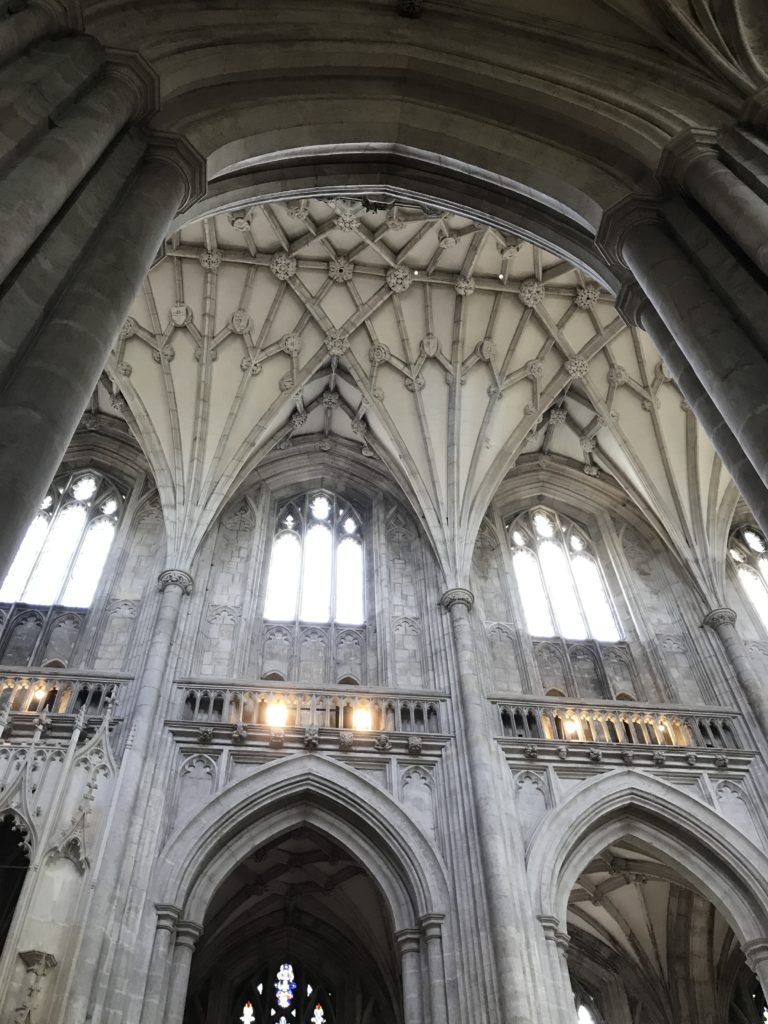

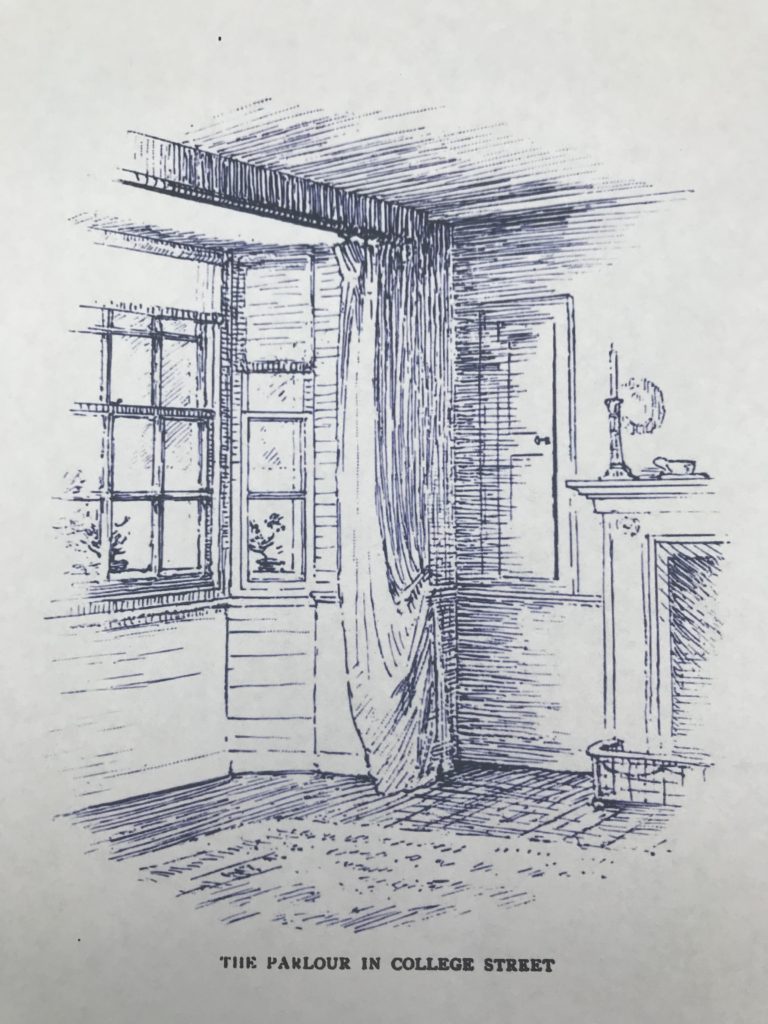

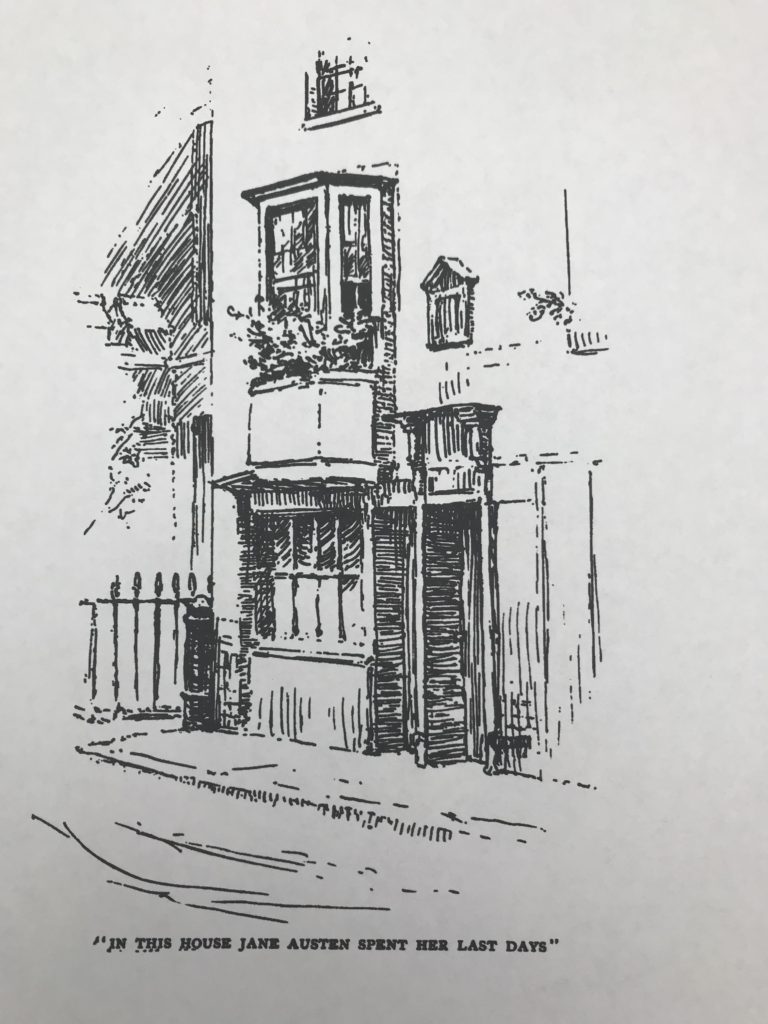

The last few weeks: By the end of May, 1817, Jane was very ill, barely moving from her bed or the sofa and the family decided that she should travel to Winchester to consult with a physician there. Cassandra accompanied her and they rented a place in College Street, very close to the cathedral. Jane wrote to her nephew that the place was comfortable; it had a front bow window and overlooked the garden across the street. As she sat writing at the window, Jane could look across the garden walls and see the tops of trees and the cathedral looming in the distance.

She spent most of her time on the sofa in the front room, was allowed to walk from room to room, and went out in a sedan chair. When she was better, she wanted go out in a wheeled chair.

Source: Jane Austen: Her Homes & Her Friends, by Constance Hill.

Better, was not to be.

The physician was grave, and although Jane’s health had vacillated even in the month or so at Winchester, he thought the end was near. And still, in a brief moment of cheer and somewhat better health, on July 15th, Jane dictated a poem to Cassandra, possibly being still too weak to write it herself. It was St. Swithin’s Day—the cathedral at Winchester is dedicated to him. And, in 1817, that was also the day of the Winchester races. In her poem, St. Swithin reprimands the citizens for frivolously indulging on races on his name day without his permission.

Two days later, on the evening of July 17th, Cassandra returned to the lodgings from an errand to find Jane had had a seizure. The doctor came and gave her something to ease her discomfort. When she fell unconscious, Cassandra sat with her for a long while on the bed, Jane’s head on her lap, gave up the vigil after a few hours to her sister-in-law, and came back to Jane at 3 a.m.

An hour later, on Friday, July 18th, 1817, Jane Austen died in her sister’s arms.

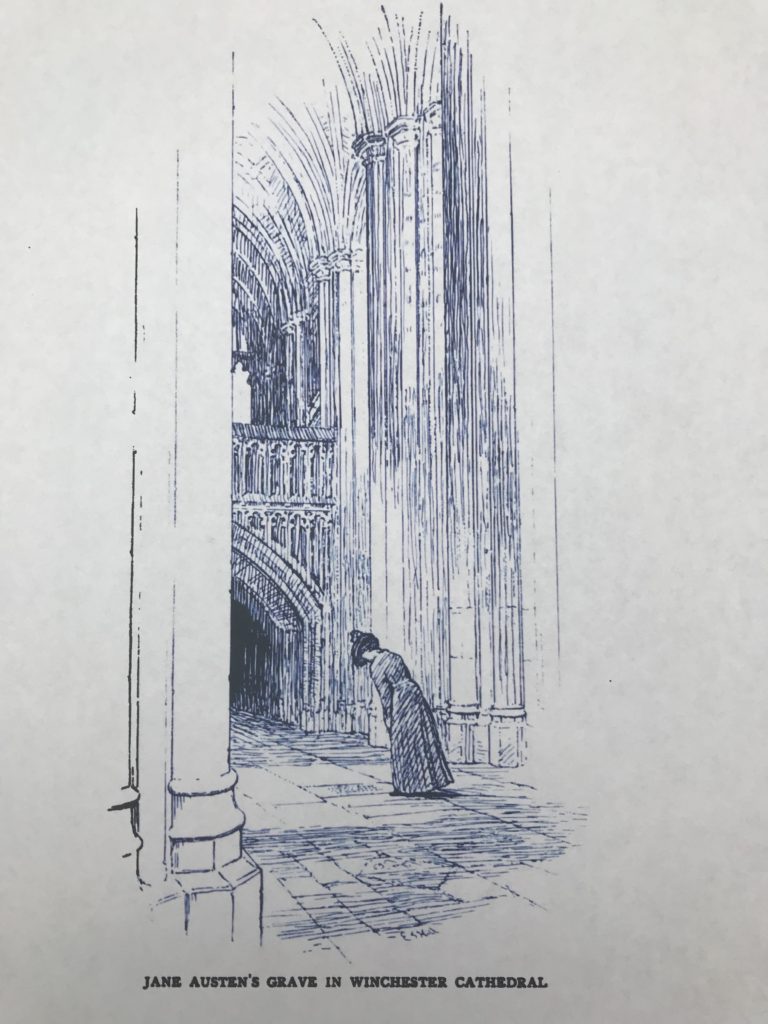

Source: Jane Austen: Her Homes & Her Friends, by Constance Hill.

It must have been devastating for all of them, especially for Cassandra, whose companion Jane had been ever since they were very little. And, Cassandra had looked after her in the past year, at Chawton, and now at Winchester during her final illness. Very early on, when both the girls were sent away to school together, and Jane was too young to be away from home, their mother had said that Jane insisted on going where Cassandra went. “If Cassandra were going to have her head cut off, Jane would insist on sharing her fate.”

Two days after Jane’s death, Cassandra wrote to their niece, Fanny Knight. “I have lost a treasure, such a sister, such a friend as can never have been surpassed. She was the sun of my life, the gilder of every pleasure, the soother of every sorrow; I had not a thought concealed from her and it is as if I had lost a part of myself.”

It’s a surprisingly lucid letter for a grieving sister, just two days after Jane’s death. But they had all been ready for it. The physician they had come to consult at Winchester had held out little hope. So, they were prepared.

Cassandra did not attend the funeral or the burial on the 24th of July, 1817 in Winchester Cathedral. Instead, from that bow window, she watched the funeral cortege go down the length of College Street and out of sight. In writing of this, she said she was numb then, didn’t feel much, but putting those words down on paper brought the weight of her sorrow upon her.

After Jane: Cassandra went home to Chawton and her mother. For a while at least, everything must have reminded her of Jane. The Clementi piano in the parlor where Jane practiced every morning before breakfast, so as to not disturb the rest of the household. Having to make the tea and toast for breakfast every morning—which Jane had done as part of her household duties. The books all over the house, which they all read and discussed. The needlework frame. The topaz cross, one of two that their brother, Charles, had bought for them with his first prize money in the navy. The little round table and chair, tucked away at one corner of the dining room, near the window, where Jane wrote every day. And, the finished and unfinished manuscripts.

Persuasion and Northanger Abbey were published posthumously. Jane’s brother Henry must have read and corrected the proofs before publication. I hope he didn’t make too many changes, and that the novels are just as Jane wrote them.

Mrs. Austen died in 1827 and Cassandra in 1845. They’re both buried in the graveyard of the church at Chawton. A couple of years before her death, around 1843, when Jane’s fame had grown already, Cassandra destroyed a chunk of her letters—including that gap between 1801 and 1804 when Jane’s letters do not exist. It was during that time that Jane fell in love with someone perhaps (around that time anyhow) and received her only known offer of marriage from Harris Bigg-Wither.

I’m an Austenite. I looked up that word, even though I’m sure I’ve heard it before to describe Austen fans. Turns out it’s some sort of ‘solid solution of carbon and iron.’

Whatever.

But, I started on this Austenite thread to say that I’ve read Austen’s books over and over again. Read biographies. Read the letters. And now, visited Austen country. And, for the last few weeks, I’ve been writing the Steventon (Part 1, Part 2), Chawton (Part 1, Part 2 and Part 3) and Winchester blog posts (Part 1 here)—reliving Jane’s life, if you will. So, when I got to this point, when she dies—and even though I know she’s been dead for about 200 years—I choked up a bit there.

Now I lay me down to sleep: Only four people attended the funeral on the 24th of July, 1817, of necessity before 10 a.m., because the cathedral service began at that time. Jane’s brothers Edward Knight, Henry Austen and Francis Austen were there, and the only person from the next generation was her nephew James Edward Austen-Leigh (her first biographer) who came to represent his father James Austen.

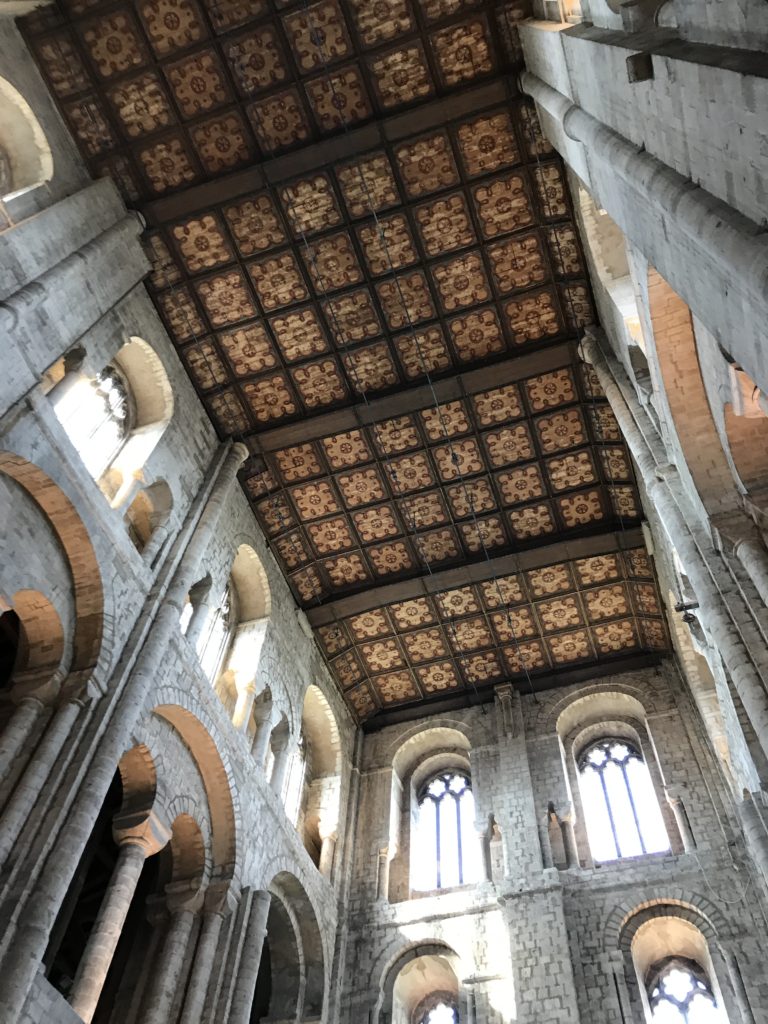

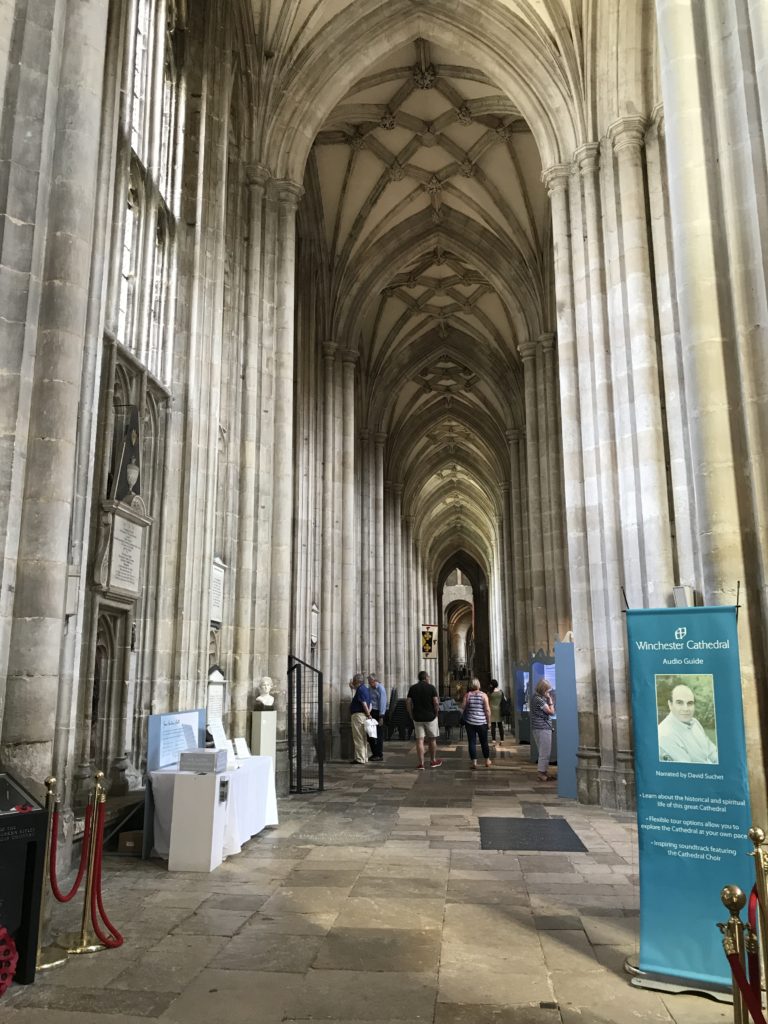

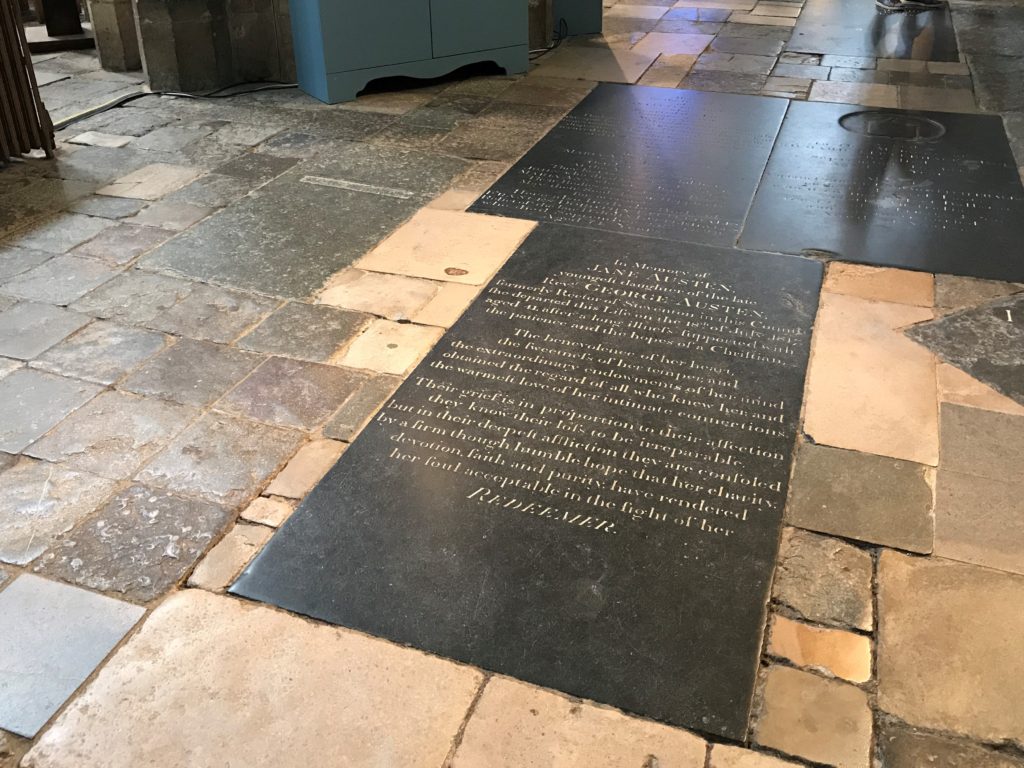

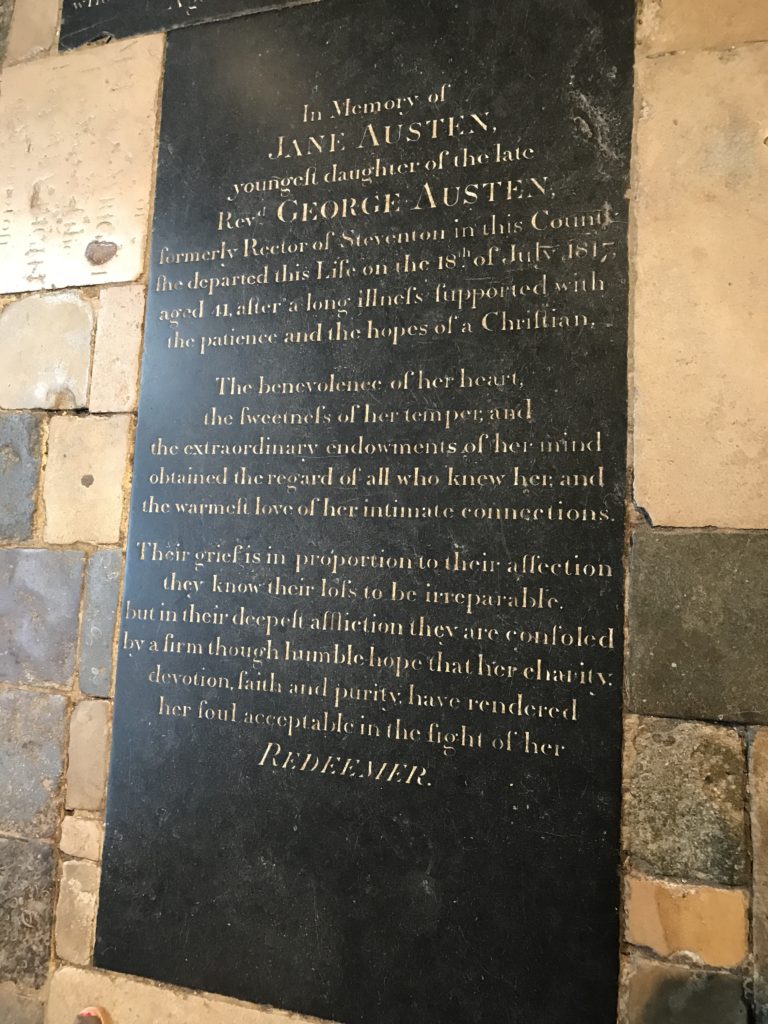

A vault had been opened on the floor of the north aisle. A service was read, and Jane was laid to rest, with a temporary stone over her grave.

Jane Austen had published her books under the cover of being, merely, ‘A Lady.’ By the time she died, true, her name had got out (Henry, her brother, is said to have delightedly revealed it), and so friends knew, family knew, friends of friends knew. Even the Prince Regent (later King George IV) got into the action—he asked his head librarian to invite Jane to his opulent residence in London, Carlton house. The Prince Regent didn’t take the trouble to meet one of his favorite authors himself; the librarian met her instead, showed her around a bit, and then came to the point. The result was that her next novel, Emma, was dedicated, respectfully etc., to the Prince Regent.

So, her fame was spotty—she was well read enough, it is true, but most people didn’t know who she was. It was, naturally, nothing as it is now, but it was something.

And yet, when her brother Henry wrote out the epitaph on the black marble stone that covers her grave, he mentioned ‘the benevolence of her heart,’ and the ‘sweetness of her temper,’ and the only nod to her genius is the oft-used, ‘the extraordinary endowments of her mind.’ That’s it. That was all he said about possibly the most famous author in the world.

Today, two hundred years later, millions of people have visited Jane Austen’s grave in Winchester Cathedral. It’s an unimaginable sort of fame, tethered only to posterity, and un-forecastable unless you can time-travel into the future.

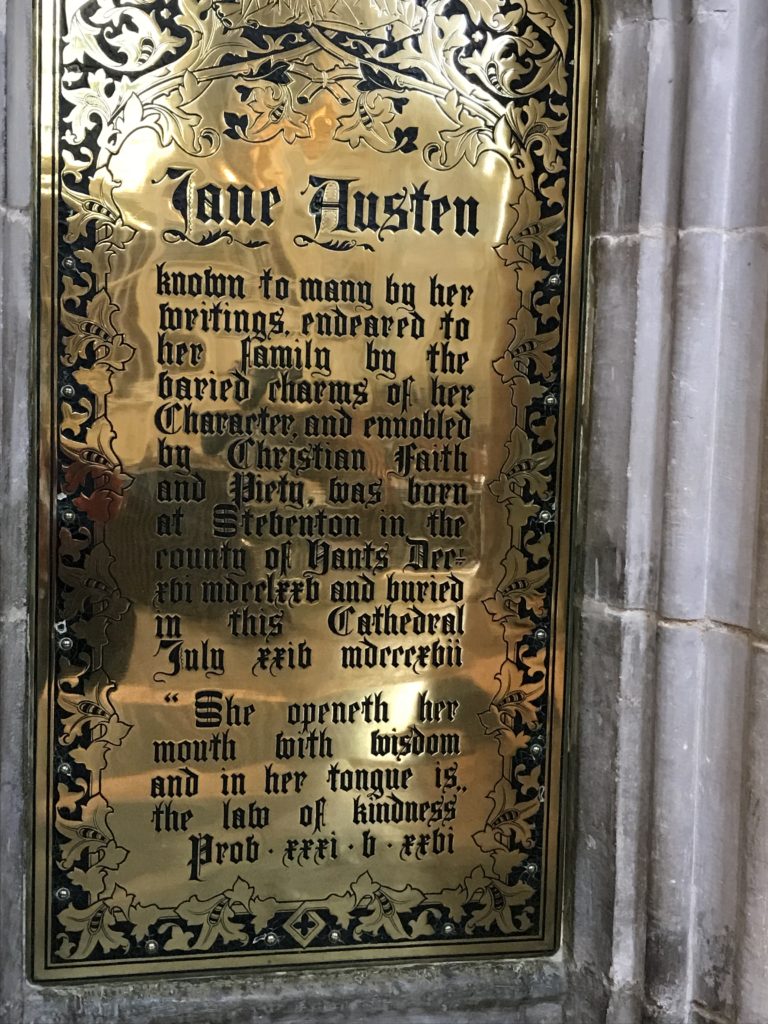

James Edward Austen-Leigh, Jane’s nephew by her eldest brother James Austen, published the first biography of his aunt in 1869, and it was an immediate success. From the profits of the sale of the memoir, he placed a brass plaque near the grave, and here, finally Jane Austen was ‘known to many by her writings.’ Later, a memorial window was erected near the grave.

When Thomas Hardy died (see Part 1 and Part 2 of the Max Gate blog posts), he was famous enough that a furor started about where he should be buried. He had wanted to rest in the local church in Stinsford, and his family wanted that also, but others insisted on a full, state-like burial at Westminster Abbey. So, he was buried in London, and his heart rests in St. Michael’s church in Stinsford, near his beloved home Max Gate.

But Jane Austen never reached that sort of celebrity in her lifetime. She published her first novel in 1811, and others as the author of that first novel, and while people came to know who she was, most notably the Prince Regent, she still died quietly. It’s a wonder at all that she is buried in Winchester Cathedral, and that only because her brother Henry, a clergyman himself, pulled a few strings.

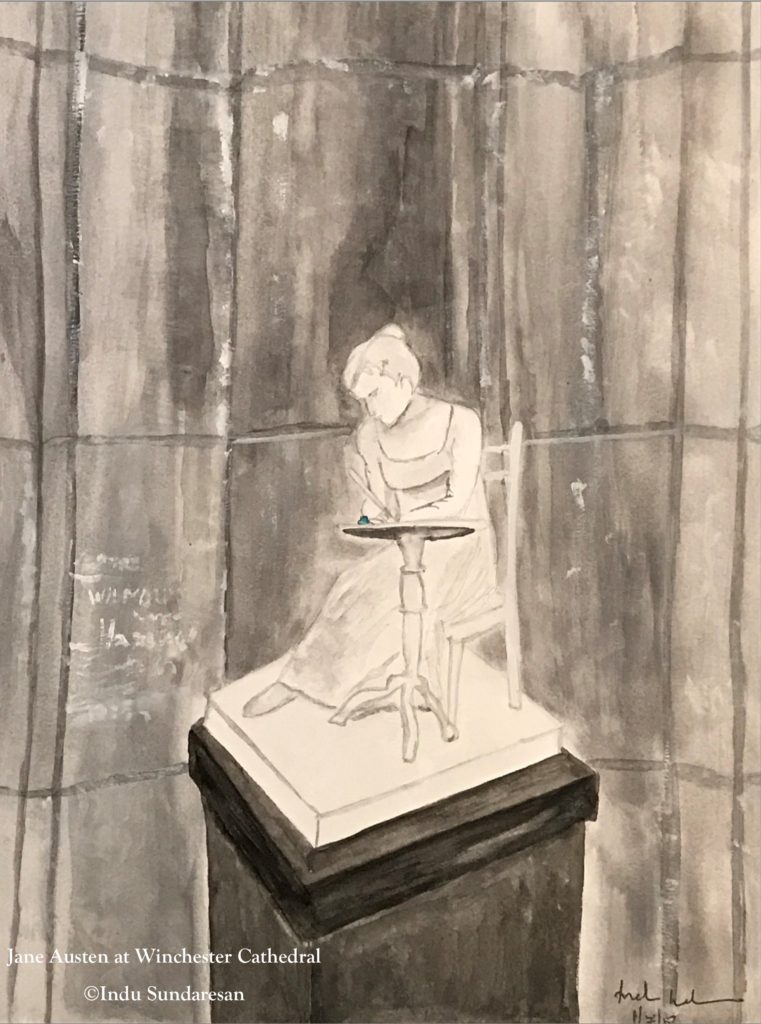

Today, a sort of running exhibit on Jane Austen, mostly on printed cardboard, is arranged around her grave. And, tucked away in one corner near the grave is this extraordinarily beautiful plaster figure of a young woman, seated on a chair, leaning over papers on a small table—very much like the table and chair that Jane wrote on in Chawton Cottage.

Our visit to Winchester Cathedral came at the end of a long day of mostly Austen country. We visited the places where she had lived, and now where she died and is buried. That statue was a pleasant surprise. I’m sure the face is not like hers at all, maybe not even the shape. But, having followed Jane Austen around for a bit, and now standing over her grave, it felt like I saw her again and understood more about her than I had hitherto.

I’m not done with Jane Austen yet, and have two more blog posts planned about her writing and her loves, but, for those of you who are not Austenites like me, we will head elsewhere for a bit before circling back to Austen.

If you’ve enjoyed reading this, please consider sharing by emailing a link to the post, and by hitting the social media share buttons below, so others may read also. Thank you!

Keyword Phrases: What is Winchester Cathedral famous for; Who is buried in Winchester Cathedral; Winchester cathedral photos; Winchester Cathedral England

On the next blog post—we take a break from Austen and head to Bath for a dip in healing waters—The Roman Baths at Bath—Part 1

Nice Post

Thanks!